Those of you who dabble with chemical structures while prosecuting or litigating pharmaceutical patents may find Allergan v. Barr Laboratories, Inc., interesting. In this ANDA litigation brought by Allergan against Barr, Teva, and Sandoz ("Barr"), the Federal Circuit opined on issues of claim construction and obviousness with respect to Allergan's Lumigan®, an ophthalmic solution used to treat high eye pressure in people with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. The active ingredient in Lumigan® is bimatoprost (cyclopentane N-ethyl heptenamide-5-cis-2-(3a-hydroxy-5-phenyl-1-trans-pentenyl)-3, 5-dihydroxy, [1a,2ß,3a,5a]):

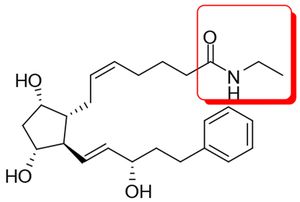

Those of you who dabble with chemical structures while prosecuting or litigating pharmaceutical patents may find Allergan v. Barr Laboratories, Inc., interesting. In this ANDA litigation brought by Allergan against Barr, Teva, and Sandoz ("Barr"), the Federal Circuit opined on issues of claim construction and obviousness with respect to Allergan's Lumigan®, an ophthalmic solution used to treat high eye pressure in people with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. The active ingredient in Lumigan® is bimatoprost (cyclopentane N-ethyl heptenamide-5-cis-2-(3a-hydroxy-5-phenyl-1-trans-pentenyl)-3, 5-dihydroxy, [1a,2ß,3a,5a]):  (The ethyl amide moiety in the red square is where all the action was focused in the case.) Allergan asserted claim 10 of U.S. Patent No. 5,688,819 ("the '819 patent"), which recited a method of treating ocular hypertension or glaucoma with a compound selected from a Marksuh group of five compounds listed by their chemical name. Bimatoprost was one of them.

(The ethyl amide moiety in the red square is where all the action was focused in the case.) Allergan asserted claim 10 of U.S. Patent No. 5,688,819 ("the '819 patent"), which recited a method of treating ocular hypertension or glaucoma with a compound selected from a Marksuh group of five compounds listed by their chemical name. Bimatoprost was one of them.

Claim Constructions

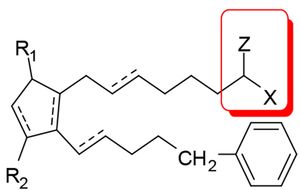

Barr had argued that bimatoprost did not fall within the scope of claim 5, from which claim 10 ultimately depended. Claim 5 recited a method of treating ocular hypertension or glaucoma using a compound of formula  where Z can be =O and X can be –N(R4)2, "wherein R4 is selected from the group consisting of hydrogen, a lower alkyl radical having from one to six carbon atoms . . . ." The issue was framed as whether claim 5 encompassed compounds in which the two R4 moieties of "-N(R4)2" must be identical or could differ (as required by bimatoprost, where one R4 moiety must be hydrogen and the other C2-alkyl). Both the District Court and the Federal Circuit held that claim 5 encompassed compounds in which the R4 moieties were non-identical.

where Z can be =O and X can be –N(R4)2, "wherein R4 is selected from the group consisting of hydrogen, a lower alkyl radical having from one to six carbon atoms . . . ." The issue was framed as whether claim 5 encompassed compounds in which the two R4 moieties of "-N(R4)2" must be identical or could differ (as required by bimatoprost, where one R4 moiety must be hydrogen and the other C2-alkyl). Both the District Court and the Federal Circuit held that claim 5 encompassed compounds in which the R4 moieties were non-identical.

Barr argued that the plain meaning of "-N(R4)2" required identical R4 moieties, relying on extrinsic evidence such as, for example, expert testimony that "[t]he (X)y nomenclature" was "commonly used" to represent identical substituents. The Federal Circuit was unpersuaded, relying heavily on Phillips v. AWH Corp. for the proposition that claim terms are to be given the meaning as one of ordinary skill in the art would understand them in the context of how they are used in the patent at issue and concluding, "[t]he inventor's lexicography governs when the specification reveals a special definition given to a claim term by the patentee that differs from the meaning it would otherwise possess."

Barr argued that the plain meaning of "-N(R4)2" required identical R4 moieties, relying on extrinsic evidence such as, for example, expert testimony that "[t]he (X)y nomenclature" was "commonly used" to represent identical substituents. The Federal Circuit was unpersuaded, relying heavily on Phillips v. AWH Corp. for the proposition that claim terms are to be given the meaning as one of ordinary skill in the art would understand them in the context of how they are used in the patent at issue and concluding, "[t]he inventor's lexicography governs when the specification reveals a special definition given to a claim term by the patentee that differs from the meaning it would otherwise possess."

In arriving at the conclusion that "-N(R4)2" encompassed compounds in which the R4 moieties were non-identical, the Court pointed to the fact that of the five compounds recited in claim 10 (which, you'll remember, depended from claim 5), three (including bimatoprost) possessed an "-N(R4)2" moiety having non-identical R4 moieties. The Court also noted that same relationship between claim 18 (which recited the same three compounds) and claim 11 (which recited a method of treating other diseases using compounds defined in the same manner as claim 5. (It's of some interest to note that the specification used the exact same language at issue in the claims.) And, finally, the Court noted that the specification disclosed the same three compounds as useful in the pharmaceutical compositions and methods of the invention. The Court held that in this context the patent clearly manifested that "-N(R4)2" encompassed compounds with non-identical R4 moieties.

Practice tip: Save yourself a lot of heartache and your client a lot of money, and in these situations define R4 more clearly, such as, "each R4 is independently selected from . . . ."

Obviousness

The Federal Circuit next considered the Barr's assertion that claim 10 (the method of treating glaucoma using one of bimatoprost or four other compounds) was obvious, first (a) dismissing the credibility of the defendants' expert, who was described as being "eviscerated" (ouch!) on cross examination and whose testimony was "flawed on a fundamental level" and (b) determining that the nature of the involved technology did not lend itself to lay interpretation, but required expert testimony. This appears to have left Barr in the position of having to rely on the plaintiff's experts, an uncomfortable position, one imagines, at best. As explained below, and not surprisingly, the defendants were unable to extract the support they needed to carry their burden of proving the claim obvious.

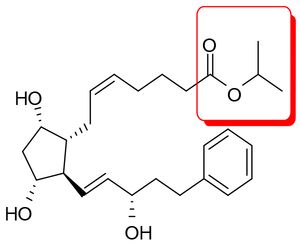

Barr asserted that bimatroprost was obvious over the isopropyl ester analog of compound 2 of Stjernschantz (WO 90/02253 [sic, WO 90/02553]),  which was disclosed as useful for treating the very same conditions as bimatoprost. The defendants argued that the plaintiff's expert testimony supported three facts necessary to establish obviousness:

which was disclosed as useful for treating the very same conditions as bimatoprost. The defendants argued that the plaintiff's expert testimony supported three facts necessary to establish obviousness:

(1) Stjernschantz taught that bimatoprost-free acid lowered intraocular pressure;

(2) Stjernschantz's compound 2 hydrolyzed into bimatoprost-free acid when placed in the eye; and

(3) a skilled artisan would have known that substituting an amide for the ester at the C-1 position would result in a prodrug that hydrolyzed into bimatoprost-free acid in the eye.

In not so many words, the Federal Circuit held, "close, but no cigar," finding that although Allergan's expert testimony supported the first two points, the testimony in fact contradicted the third point. Allergan's expert testified that an amide (such as found in bimatoprost) converts into a carboxylic acid at such a low rate ("500-year half life" of an amide in water) that one of ordinary skill in the art would not have considered it as a prodrug. With Barr left empty-handed expert-wise, Allergan's expert opinion prevailed, and the Federal Circuit upheld the District Court's finding that claim 10 was not invalid as obvious.

Allergan, Inc. v. Barr Laboratories, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2013)

Panel: Chief Judge Rader and Circuit Judges Bryson and Wallach

Opinion by Circuit Judge Wallach