Judge T.S. Ellis III of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia wrote the latest chapter in the story of  judicial review of (and, generally, disagreement with) how the Office has interpreted the patent term adjustment provisions of the 1999 America Inventors Protection Act (AIPA). This case involves so-called "B delay," corresponding to a date that is three years after an application's filing date and the date on which the Office actually grants a patent pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(B). The issue was whether the Office had correctly implemented the statute by negating B delay in circumstances where an applicant had responded to a final rejection by filing a request for continued examination (RCE) (also a provision newly added to U.S. patent law by the AIPA).

judicial review of (and, generally, disagreement with) how the Office has interpreted the patent term adjustment provisions of the 1999 America Inventors Protection Act (AIPA). This case involves so-called "B delay," corresponding to a date that is three years after an application's filing date and the date on which the Office actually grants a patent pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(B). The issue was whether the Office had correctly implemented the statute by negating B delay in circumstances where an applicant had responded to a final rejection by filing a request for continued examination (RCE) (also a provision newly added to U.S. patent law by the AIPA).

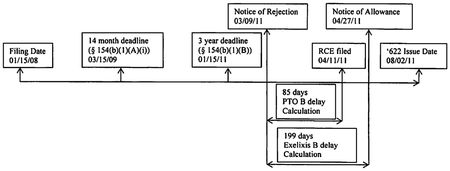

The case involved an application filed by Exelixis that resulted in grant of U.S. Patent No. 7,989,622 entitled "Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Inhibitors and Methods of their Use." The application was filed on January 15, 2008 and a first Office Action promulgated by the Office on February 22, 2010, resulting in an "A delay" (the time from the filing date to the first substantive action in a case pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(A)) of 283 days. The PTO issued Final Rejection on March 9, 2011 (38 months, i.e., 2 months from the three-year date calculated from the filing date), to which the applicants responded on April 11, 2011; this response was filed with an RCE. "Less than three weeks later" (a time the Court characterized as "commendable, if, with respect to this application, uncharacteristic alacrity"), the Office issued a Notice of Allowance. Despite payment of the Issue Fee almost immediately (on April 28, 2011), the patent did not grant until August 2, 2011. At that time, the Office notified Exelixis that the PTA for this patent was a total of 368 days, corresponding to 283 days of A delay, 85 days of B delay, 0 days of C delay under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(C) and subtracting 61 days for applicant delay in prosecution ("C reduction" under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(C)). The Office's calculation of the B delay, the issue in the case, credited Exelixis for 85 days from the time between the date that was three years after the application was filed and the date the Final Rejection was mailed; the Office did not give this patent the benefit of another 114 days corresponding from the date the RCE was filed until the grant date, implementing Office policy that filing an RCE stops the accumulation of B delay in the Office's PTA calculation. These 114 days and the Office's policies that deprived the '622 patent of this additional PTA prompted the lawsuit. The Court set forth a helpful timeline:

The case involved an application filed by Exelixis that resulted in grant of U.S. Patent No. 7,989,622 entitled "Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Inhibitors and Methods of their Use." The application was filed on January 15, 2008 and a first Office Action promulgated by the Office on February 22, 2010, resulting in an "A delay" (the time from the filing date to the first substantive action in a case pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(A)) of 283 days. The PTO issued Final Rejection on March 9, 2011 (38 months, i.e., 2 months from the three-year date calculated from the filing date), to which the applicants responded on April 11, 2011; this response was filed with an RCE. "Less than three weeks later" (a time the Court characterized as "commendable, if, with respect to this application, uncharacteristic alacrity"), the Office issued a Notice of Allowance. Despite payment of the Issue Fee almost immediately (on April 28, 2011), the patent did not grant until August 2, 2011. At that time, the Office notified Exelixis that the PTA for this patent was a total of 368 days, corresponding to 283 days of A delay, 85 days of B delay, 0 days of C delay under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(1)(C) and subtracting 61 days for applicant delay in prosecution ("C reduction" under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b)(2)(C)). The Office's calculation of the B delay, the issue in the case, credited Exelixis for 85 days from the time between the date that was three years after the application was filed and the date the Final Rejection was mailed; the Office did not give this patent the benefit of another 114 days corresponding from the date the RCE was filed until the grant date, implementing Office policy that filing an RCE stops the accumulation of B delay in the Office's PTA calculation. These 114 days and the Office's policies that deprived the '622 patent of this additional PTA prompted the lawsuit. The Court set forth a helpful timeline:

The Court recognized the context of the dispute being based in an assessment of Congressional intent in implementing the provisions of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which changed the term of U.S. patents from 17 years from issue to 20 years from the filing (or earliest priority) date, and the provisions of the AIPA apparently aimed at restoring term lost as the result of Patent Office delays in prosecution. "Taken as a whole," the Court said:

[T]he clear goal and purpose of these provisions is to provide a successful applicant with a patent that can be enforced against putative infringers for approximately 17 years -- 20 years from the date of application less three years for prosecution and examination -- and to reach this goal by providing applicants with day for day patent term extension for delays attributable to the PTO and day for day reductions for the patent term extension for delayed attributable to an applicant's failure to act with alacrity in certain circumstances.

The Court characterizes the provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 154(b) as "guarantees" according to the titles of the three sections of § 154(b) relating to PTO delay, which is significant because the Court notes (in a footnote) that it is permissible for courts to use titles and headings in statutes in interpreting the meaning of the substantive provisions of law.

On summary judgment, the Court ruled against the PTO's interpretation of the statute based on its construction of the statutory provisions and Congressional intent discerned inter alia from how Congress described and characterized those provisions in the statute. The Court applied the deferential standard that agency action must be upheld unless it is "arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion or otherwise not in accordance with law" under the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A)), noting that an erroneous interpretation of the law satisfies this standard, citing Star Fruits S.N.C. v. U.S., 393 F.3d 1277, 1281 (Fed. Cir. 2005), and Arnold Partnership v. Dudas, 362 F.3d 1338, 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

The Court's opinion begins with the "plain language of the statute," and the Court found that the meaning of the statute was "clear, unambiguous, and in accord with both the statute's structure and purpose." Section 154(b)(2) clearly and "simply" is intended by its terms to provide a guarantee of no more than a three-year application pendency, according to the Court's opinion, and this goal is accomplished by "(i) starting a three year clock on the date the application is filed, (ii) tolling the running of this clock if, within the three year period, any of three events occur, including an RCE filing, and (iii) adding a day for day PTA to the patent term for any delay in the issuance of a patent after the three year clock, less any tolling, runs out."

In the Court's view, the provisions of the statute involving RCEs have to do solely with tolling the clock with regard to the three-year date. The opinion states that the portion of the statute concerning RCEs "clearly and unambiguously modifies and pertains to the three year period and does not apply to, or refer to, the day to day PTA remedy." The Court characterizes as "[e]specially notable" that the statute "does not address the filing of an RCE after the expiration of the three year clock" (emphasis in original). The statute "makes [it] clear that once the three year clock has run, PTA is to be awarded on a day for day basis regardless of subsequent events" in the Court's view. The Court also notes that the filing of an RCE is not contained in the section setting forth the day to day reduction in PTA occasioned by applicant delay in prosecution, and concludes that the statute does not consider the filing of an RCE to be an action that warrants reduction in PTA under the statute. The Court concludes that "RCE's gave no impact on the PTA after the three year deadline has passed."

The Court rejected PTO arguments in favor of the Office's interpretation. Specifically, the opinion swiftly dismissed the argument that the statute must be interpreted as if it included the word "then" in such a way that would support its interpretation by simply noting that the word "then" did not appear in the statute and on the grounds that the Office's interpretation would effectively treat the filing of an RCE as a failure to "engage in reasonable efforts to conclude prosecution of the application," i.e., the grounds for applicant delay where the Court had expressly found RCE filings were not included. If this is the interpretation the Office wants to apply to RCEs, the Court tartly recommends that the Office should be sure to "issue any notice of rejection prior to the expiration of the three year period" as well as require prompt filing of an RCE. The Court also rejects the Office's position that it should be accorded deference, saying that "deference is unwarranted when [] the statute is unambiguous." In this regard the Court notes that the Federal Circuit had rejected this level of deference in the last case decided on PTA issues, Wyeth v. Kappos. Finally, the Court noted that any disparate treatment that might result one application to the next (depending on whether an RCE was filed before or after the 3-year anniversary date) was something within the Office's power to control or minimize.

It is likely that the government will appeal to the Federal Circuit, and thus that the finality of this interpretation of the statute will remain delayed until that review of complete. This means that there is time for prudent patent practitioners to review the PTA status of their clients' patents to determine where there are instances where the PTA was "improperly" calculated under the interpretation set forth in this opinion. But time may be of the essence for some because the statute also imposes a 180-day statute of limitations on filing challenges to Office PTA determinations (see "USPTO Posts Notice Regarding Wyeth Decision"), and while an intervening change in the law may permit challenges outside that period it makes better sense to identify important patents and file a lawsuit based on this interpretation of the B delay statutory provisions to best protect both clients and practitioners.

Exelixis, Inc. v. Kappos (E.D. Va. 2012)

Memorandum Opinion by Judge T.S. Ellis, III