When can a district court's factual findings related to the extrinsic evidence in a claim construction determination not be given deference by the Federal Circuit? At least one situation is when the findings do not "override" "the totality of the specification," especially when the specification "clearly indicates . . . the purpose of [the] invention . . . ." This is what the Federal Circuit held earlier this week in the Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera Corp. case. Writing for the majority, Chief Judge Prost noted that the intrinsic evidence for a patent related to modifying polynucleotides to be used with nucleic acid probes suggested that the claims could only be directed to detection by indirect means (such as with biotin/avidin or antibody/antigen complexes). As a result, the District Court's claim construction was vacated, as was the jury verdict of infringement, and the case was remanded for further findings based on the new claim construction. Judge Newman dissented, pointing out that if the expert testimony was given its proper deference, the correct outcome would have been affirmance.

When can a district court's factual findings related to the extrinsic evidence in a claim construction determination not be given deference by the Federal Circuit? At least one situation is when the findings do not "override" "the totality of the specification," especially when the specification "clearly indicates . . . the purpose of [the] invention . . . ." This is what the Federal Circuit held earlier this week in the Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera Corp. case. Writing for the majority, Chief Judge Prost noted that the intrinsic evidence for a patent related to modifying polynucleotides to be used with nucleic acid probes suggested that the claims could only be directed to detection by indirect means (such as with biotin/avidin or antibody/antigen complexes). As a result, the District Court's claim construction was vacated, as was the jury verdict of infringement, and the case was remanded for further findings based on the new claim construction. Judge Newman dissented, pointing out that if the expert testimony was given its proper deference, the correct outcome would have been affirmance.

This case has been going on for over 10 years (2004), when Enzo and Yale University filed suit against Applera and Tropix for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 5,449,767 (the '767 patent), among others, in the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut. In fact, this is not the first time this case has been before the Federal Circuit. In 2010, this Court reversed a summary judgment determination that the '767 patent was invalid, although the invalidity and non-infringement determination of other patents were upheld (see "Enzo Biochem, Inc. v. Applera Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2010)"). Ultimately, the case went to trial, and the jury returned a verdict for Enzo in the amount of around $48.5 million. In early 2014, Judge Arterton added pre-judgement interest in the amount of around $12.5 million, for a total of around $61 million.

This case has been going on for over 10 years (2004), when Enzo and Yale University filed suit against Applera and Tropix for infringement of U.S. Patent No. 5,449,767 (the '767 patent), among others, in the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut. In fact, this is not the first time this case has been before the Federal Circuit. In 2010, this Court reversed a summary judgment determination that the '767 patent was invalid, although the invalidity and non-infringement determination of other patents were upheld (see "Enzo Biochem, Inc. v. Applera Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2010)"). Ultimately, the case went to trial, and the jury returned a verdict for Enzo in the amount of around $48.5 million. In early 2014, Judge Arterton added pre-judgement interest in the amount of around $12.5 million, for a total of around $61 million.

The '767 patent was directed to "Modified Polynucleotides and Methods of Preparing Same." As the opinion explains, these modified polynucleotides can be used in probes, which can be used to identify the presence of nucleic acids in a sample. For example, these probes can be used to sequence DNA. Previously, the probes were labeled with radioactive isotopes, although this was not ideal because they were hazardous, expensive, and unstable. Measuring the radioactive signal was a form of direct detection. The polynucleotides of the present patent instead contained a nucleotide with a constituent "A" that was "at least three carbon atoms and represent[ed] at least one component of a signaling moiety capable of producing a detectable signal." At issue was the District Court's claim construction of this term from 2006, as well as the phrase "signaling moiety." Put simply, the issue was whether the claim terms covered just indirect detection, or both direct and indirect.

Independent Claim 1 was (with the relevant language underlined):

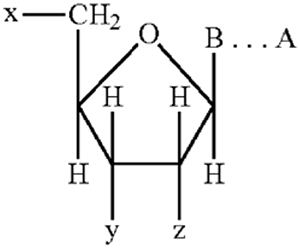

1. An oligo- or polynucleotide containing a nucleotide having the structure:

wherein B represents a 7-deazapurine or a pyrimidine moiety covalently bonded to the C1 '-position of the sugar moiety, provided that whenever B is a 7-deazapurine, the sugar moiety is attached at the N9 -position of the 7-deazapurine, and whenever B is a pyrimidine, the sugar moiety is attached at the N1 -position of the pyrimidine;

wherein A comprises at least three carbon atoms and represents at least one component of a signaling moiety capable of producing a detectable signal;

wherein B and A are covalently attached directly or through a linkage group that does not substantially interfere with the characteristic ability of the oligo- or polynucleotide to hybridize with a nucleic acid and does not substantially interfere with formation of the signalling moiety or detection of the detectable signal, provided also that if B is 7-deazapurine, A or the linkage group is attached to the 7-position of the deazapurine, and if B is pyrimidine, A or the linkage group is attached to the 5-position of the pyrimidine;

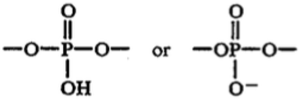

wherein one of x and y represents

and the other of x and y is absent or represents --OH or --H; and

wherein z represents H-- or HO--.

The Court started with the language of the claim, noting that "at least one component" indicates that the signaling moiety has multiple parts. Also, the fact that the attachment of "A" does not interfere with the formation of the signaling moiety suggests that the claimed compound does not include a "formed" signaling moiety. Judge Newman pointed out, however, that the use of the phrase "at least one" has been consistently interpreted to mean "one or more." Also troubling was the context of claim 1 in relation to its dependent claims. The first set of claims was drawn to indirect detection embodiments, such as claim 3:

3. An oligo- or polynucleotide of claim 1 wherein A is a ligand.

Claim 67, however, represented a set of dependent claims that were drawn to direct detection.

67. An oligo- or polynucleotide of claim 1 or 48 wherein A comprises an indicator molecule.

If claim 1 can have dependent claims drawn to both direct and indirect detection, the District Court reasoned, the claim certainly cannot be limited to just one of these. The Federal Circuit, however, was dismissive of District Court's reliance on these claims. The Federal Circuit concluded that "dependent claims cannot broaden an independent claim from which they depend." It is unclear, however, why these dependent claims were not be used to define the scope of claim 1 in the first place.

The Court continued by looking to the specification. It is black letter patent law that the description of a preferred embodiment should not be used to limit the claims to that particular embodiment. In this case, though, the Federal Circuit stated that the "background portion of the specification further describes the invention," which was used to support the narrowing of claim 1 to indirect detection mechanisms. The section of the specification cited is reproduced here:

To circumvent the limitations of radioactiviely labeled probes or previously utilized chemical and biological probes, a series of novel nucleotide derivatives that contain biotin, iminobiotin, lipoic acid, and other determinants attached covalently to the pyrimidine or purine ring have been synthesized. These nucleotide derivatives, as well as polynucleotides and coenzymes that contain them, will interact specifically and uniquely with proteins such as avidin or antibodies. The interaction between modified nucleotides and specific proteins can be utilized as an alternative to radioisotopes for the detection and localization of nucleic acid components in many of the procedures currently used in biomedical and recombinant-DNA technologies.

Nowhere in this section does it mention "the present invention," much less can this be considered a clear disavowal of the claim scope that might cover direct detection methods.

The Federal Circuit also pointed to the fact that the specification only discusses direct detection. However, the Court ignored example 9, which the District Court concluded, "based on expert testimony," teaches direct detection. "[T]his sole factual finding does not override our analysis of the totality of the specification, which clearly indicates that the purpose of this invention was directed towards indirect detection, not direct detection." Whether a claim term can be limited by "the purpose of" the invention is an interesting question, but the Teva case required the Federal Circuit to give deference to findings of fact. Reliance on what an expert says about the meaning of the specification would appear to be just the type of evidence that should be entitled to the "clear error" standard. In fact, Judge Newman pointed out that the majority did not cite to any contrary evidence to support a reversal of the District Court. In addition, she pointed out that the majority also ignored Applera's expert, Dr. Kricka, who conceded on cross-examination that "several parts of the original application disclosed compounds that allowed for direct detection." The Court relied, in part, on the fact that Enzo did not raise this argument on appeal. However, is that significant, especially when the Court was explicitly interpreting claims in view of Teva, yet in a manner inconsistent with the District Court's fact findings.

As much as there was concern in the community when the Teva case came down that attorneys would be motivated to set up as many facts as possible in a claim construction proceeding, it is equally true that appellees should be motivated to cite to the district court's reliance on those factual findings. Conversely, a party seeking to reverse a claim construction determination should establish how the correct construction is clear from the claim language alone, and therefore no deference is due. Perhaps the soundness of these propositions is the best take-away lesson that can be gleaned from this case.

Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera Corp. (Fed. Cir. 2015)

Panel: Chief Judge Prost and Circuit Judges Newman and Linn

Opinion by Chief Judge Prost; dissenting opinion by Circuit Judge Newman