True Oil LLC v. BLM[1] is a recent opinion by the Wyoming Federal District Court, based on the appeal of an order out of the BLM Rawlins Field Office. At issue was whether a fee surface owner can grant a subsurface easement through federal minerals without BLM approval.[2] The district court found that the surface owner has the right to grant subsurface access, but the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) can require a federal Application for Permit to Drill (“APD”).

I. The Background

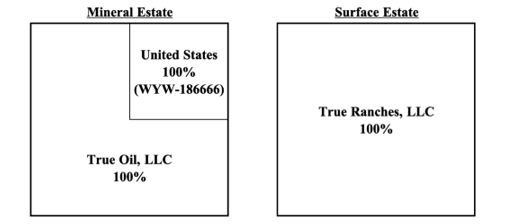

True Oil LLC (“True Oil”) owns the minerals under the NW/4 and S/2 of Section 10-T12N-R65W in Laramie County, Wyoming. The federal government owns the minerals underlying the NE/4 of Section 10, subject to Federal Lease No. WYW-186666. True Ranches LLC (“True Ranches”) owns the surface estate of Section 10.[3]

True Oil planned to drill several horizontal wells across Section 10, some of which were slated to traverse the NE/4. Due to delays in obtaining federal drilling permits and various pending environmental lawsuits,[4] True Oil decided it would drill through – but not perforate or complete within – the NE/4 of Section 10. True Oil took the position that as long as True Ranches granted permission, and no production was to take place on the NE/4, a state permit was adequate. In other words, no federal permit should be required. True Oil thus filed for an APD with the Wyoming Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (the “WOGCC”) but did not file for an APD with the BLM. The BLM took the opposite stance, informing True Oil that absent a federal APD, it would not authorize True West’s request to traverse WYW-186666.[5] Any attempt to drill through the NE/4 would result in the BLM pursuing civil and/or criminal penalties for trespass.[6]

II. Who Owns the Subsurface Rights?

The question presented to the district court was if a federal mineral estate has been severed from a fee surface estate, who holds the right to grant a subsurface easement? True Oil’s argument that this right is held by the surface owner did not persuade the court because it “relie[d] on Texas cases that do not involve federal minerals.”[7] The court instead pointed sua sponte to the Stock Raising Homestead Act of 1916 (the “SRHA”), [8] under which the original surface patent had been issued. The SRHA states that all patents issued thereunder “shall be subject to and contain a reservation to the United States of all the coal and other minerals in the lands so entered and patented . . .”[9] What remains unclear under the SRHA, is whether the United States only reserved the minerals (and the right to extract the minerals), or the subsurface geological formations themselves.[10]

The trial court first emphasized that the SRHA reserved “coal and minerals in the lands so entered and patented.” Thus, it appears that Congress intended that only the minerals within the ground be reserved to the United States, not everything under the surface. If the United States had intended to retain the entire subsurface, the SRHA could have said so expressly.[11] Moreover, if the entire subsurface was reserved, there would be no need for the extensive body of caselaw that has emerged analyzing the meaning of “minerals” under the SRHA.[12] The SRHA thus reserved only the extractable minerals to the United States, not the entirety of the soil beneath its surface.

III. Can the BLM Require an APD?

The court next analyzed whether, if the surface owner also owns the subsurface matrix embracing the minerals, the BLM has the right to require an APD to traverse the subsurface. In finding such a requirement reasonable, the court first noted that under the SRHA Congress did not fully relinquish its ability to protect the United States’ property interests below the surface.[13] Instead, Congress retained a robust ability to protect its mineral interests, including the ability to restrict subsurface activity by the surface owner. Moreover, the Property Clause of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress (and its regulatory delegatees) the right to regulate private property to protect its own.[14] Thus, it is well within the BLM’s authority to regulate subsurface activity, and such a requirement is not a complete prohibition on drilling activity. It merely provides the BLM a mechanism for monitoring activity and protecting the interests of the United States.

The court found that policy considerations support its decision because “[t]he federal government owns the mineral rights on 11 million acres of the nearly 12 million acres of split estate lands in Wyoming . . . If the surface owners on those 12 million acres could permit subsurface activity, without notice to the federal government, millions of acres of public resources could be endangered. Setting aside the risk of unpermitted extraction of federal minerals, the location and amount of traversing wells could jeopardize future extraction for those sites. The BLM needs notice and regulatory authority so it may protect the United States’ interests and preserve minerals for future extraction.”[15]

IV. Takeaway and Appeal

True Oil stands in contrast to the notion that a surface owner has the unfettered right to grant a subsurface easement as long as it does not unduly interfere with mineral extraction. It instead appears to carve out an exception for surface estates overlaying federal minerals. While the surface owner can consent to subsurface use, according to the trial court the BLM can require a permit to do so.

True Oil has potentially broad implications for everything from subsurface use agreements and easements to pore space ownership and carbon sequestration where federal minerals are involved. It the court’s decision stands, it may mean that both a severed surface owner and the BLM will need to sign off on subsurface activity. This case was appealed on December 1, 2023 and is one to keep an eye on.

References

[1] 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 221156 (D. Wyo. 2023).

[2] Note that the right to grant a subsurface easement through severed fee minerals is generally held by a surface owner. See generally Lightning Oil Co. v. Anadarko E&P Onshore, LLC, 520 S.W.3d 39 (Tex. 2017).

[3] Id. at 2.

[4] These lawsuits were pending in the U.S. District Court for the District of Montana and challenged a December 2017 oil and gas lease sale for failure to protect sage grouse habitats and other issues.

[5] Id. at 3-4.

[6] Id. at 5.

[7] Id. at 10. The court is presumably referring to Lightning Oil Co. v. Anadarko E&P Onshore, LLC and its progeny. 520 S.W.3d 39 (Tex. 2017).

[8] 43 U.S.C. §§ 291, et seq.

[9] 43 U.S.C. § 299.

[10] 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 221156 at 12.

[11] Id. at 12-13.

[12] Id. at 13. See, e.g., United States v. Union Pac. R.R. Co., 353 U.S. 112 (1957).

[13] 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 221156 at 18.

[14] Id. at 19-20.

[15] Id. at 23-24.