At some point, a legal claim is just so old and stale that it’s unfair to allow the plaintiff to bring it. The statute of limitations and the doctrine of laches are two different solutions to this same problem. The former puts specific time limits on certain types of claims. On the other hand, the equitable doctrine of laches (from the old French “laschesse,” meaning “slackness”) eschews the one-size-fits-all approach and allows a judge to use common sense and fairness to determine whether a plaintiff’s delay was unreasonable given the particular circumstances of each case.

But what happens if the statute of limitations tells you a claim is still fresh, while the doctrine of laches tells you that the very same claim is too old?

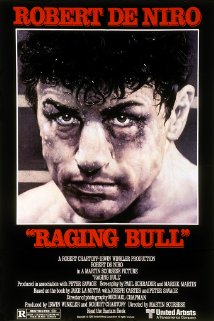

The statute of limitations on a civil copyright claim is three years, and Paula Petrella brought her claim against the distributors of the film Raging Bull within three years of the infringement about which she complained. Nevertheless, the 9th Circuit held that her claim was barred by the doctrine of laches. Now, the Supreme Court will have to resolve, in Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. , a “severe” circuit split over whether the laches defense is available at all in the copyright context. How did this split come about? The answer is buried in the uncomfortable intersection between the statute of limitations, the doctrine of laches, and the “rolling” nature of copyright infringement.

The statute of limitations on a civil copyright claim is three years, and Paula Petrella brought her claim against the distributors of the film Raging Bull within three years of the infringement about which she complained. Nevertheless, the 9th Circuit held that her claim was barred by the doctrine of laches. Now, the Supreme Court will have to resolve, in Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. , a “severe” circuit split over whether the laches defense is available at all in the copyright context. How did this split come about? The answer is buried in the uncomfortable intersection between the statute of limitations, the doctrine of laches, and the “rolling” nature of copyright infringement.

A History of Delay

In the case of the US Copyright Act, there was originally no statute of limitations. Thus, prior to 1976, judges applied the limitations periods of the jurisdictions in which they presided or, if they felt it was appropriate, used equitable doctrines such as laches to distinguish stale claims.

In 1976, Congress finally enacted a federal three-year limitations period. According to the 4th Circuit and others, this legislative enactment ought to have permanently extinguished the use of laches in the copyright context. The 2nd Circuit, on the other hand, allows laches defenses to bar injunctive relief, but not damages. Meanwhile, the 11th and 6th Circuits restrict the defense to extremely limited circumstances.

The “Rolling” Nature of Copyright Infringement

But the 9th Circuit and many others disagree, and apply laches as a defense to both damages and injunctive relief in copyright cases. After all, the argument goes, we often extend the statute of limitations for equitable reasons, so it only makes sense that the limitations period could be contracted by equity, particularly in the context of copyright where the “separate accrual” rule tends to lengthen the time period of a defendant’s potential exposure. Under that rule, each distribution of an infringing copy is a separate act of copyright infringement. For example, if you sold one infringing copy of a book each year for twenty years, each of these sales would trigger a separate copyright claim with its own three-year limitations period, such that the statute of limitations is effectively “rolling.” At the end of the twenty years, you might not be able to sue for all twenty acts of infringement, but you could still sue for the last three.

For precisely this reason, Judge Learned Hand opined in 1916 that the doctrine of laches was especially suited to copyright claims:

“It must be obvious to everyone familiar with equitable principles that it is inequitable for the owner of a copyright, with full notice of an intended infringement, to stand inactive while the proposed infringer spends large sums of money in its exploitation, and to intervene only when his speculation has proved a success. Delay under such circumstances allows the owner to speculate without risk with the other’s money; he cannot possibly lose, and he may win.”

“It must be obvious to everyone familiar with equitable principles that it is inequitable for the owner of a copyright, with full notice of an intended infringement, to stand inactive while the proposed infringer spends large sums of money in its exploitation, and to intervene only when his speculation has proved a success. Delay under such circumstances allows the owner to speculate without risk with the other’s money; he cannot possibly lose, and he may win.”

Slacking Bull

The 9th Circuit feels that this principle is no less relevant today, and should be applicable in the case of Paula Petrella. Petrella’s father, Peter, wrote a book about boxer Jake LaMotta. In 1976, he transferred his rights in the book to a film production company, which led to the 1980 motion picture, Raging Bull.

In 1990, the Supreme Court in Stewart v. Abend held that, in certain circumstances, copyright renewal rights revert to an author’s heirs even if the author signed away those rights during his life. The upshot of the ruling was that, in 1991, Petrella suddenly found herself the owner of the source material for Raging Bull, and thus arguably entitled to some of the profits from the continuing distribution of the film.

However, Raging Bull, even though it has been accorded legendary status by film critics, was not a commercial success. Demanding a piece of it in 1991 simply wasn’t worth Paula Petrella’s while. She waited until 1998, seven years later, before she even contacted the distributors of the film. When the distributors rebuffed her demands, Petrella still didn’t sue. She just kept waiting. Not until 2009, nearly 20 years after her claim accrued, did she file suit. By this time, home video versions of Raging Bull continued to be sold, the distributors were preparing for the potentially lucrative release of the 30th anniversary DVD and, presumably, the film had finally earned a profit worth suing over.

Petrella limited her claim to the alleged infringement occurring within the three years prior to her complaint, but the District court and the 9th Circuit ruled that she nevertheless had waited too long. The court held that, under the modern formulation of the doctrine of laches, Petrella’s delay was unreasonable and caused the defendants substantial prejudice, i.e. the investments they made in distribution of the film while Petrella sat on her rights.

The Question Under Review

After the 9th Circuit affirmed dismissal, Petrella filed a petition for Writ of Certioriari with the Supreme Court and, on October 1, 2013, the court granted that petition. Her argument is that the doctrine of laches and the statute of limitations cannot coexist in the copyright context, and courts ought to defer to the legislature’s three-year limitations period irrespective of equitable considerations. The question before the court is “whether the nonstatutory defense of laches is available without restriction to bar all remedies for civil copyright claims filed within the three-year statute of limitations prescribed by Congress.”