On April 21, 2014, a Federal Circuit panel reiterated its interpretation and application to the chemical arts of the KSR obviousness standard. Although applicable more broadly than the chemical arts, the opinion may be of particular interest to patent prosecutors in this technology field. A jury found the patent at issue not obvious and the Federal Circuit affirmed.

On April 21, 2014, a Federal Circuit panel reiterated its interpretation and application to the chemical arts of the KSR obviousness standard. Although applicable more broadly than the chemical arts, the opinion may be of particular interest to patent prosecutors in this technology field. A jury found the patent at issue not obvious and the Federal Circuit affirmed.

In this Hatch-Waxman litigation, the plaintiffs (patent owners and licensees) brought suit after the defendants filed an ANDA with a paragraph IV certification alleging that the claims of plaintiffs' patent 5,721,244 ("'244 patent") were obvious. The drug that was the subject of the ANDA was Tarka®, a single dosage form anti-hypertensive medication comprising a combination of the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor trandolapril and the calcium antagonist verapamil hydrochloride. There was evidence that the combination provided benefits not previously known for anti-hypertension treatment: a single daily dosage form providing longer lasting control and improved kidney function and blood vessel structure.

Claim 3 of the ’244 patent was at issue:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising:

(a) an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitor) . . . , and

(b) a calcium antagonist or a physiologically acceptable salt thereof; wherein said ACE inhibitor and said calcium antagonist are present in said composition in amounts effective for treating hypertension; . . .

3. A composition according to claim 1, wherein said ACE inhibitor is trandolapril . . . or a physiologically acceptable salt thereof, or quinapril … or a physiologically acceptable salt thereof.

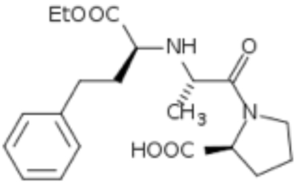

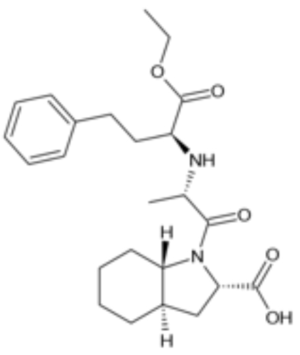

Combinations of ACE inhibitors and calcium antagonists were known in the art, although the art taught the use of so-called "single ring" ACE inhibitors like enalapril,

whereas trandolapril of the claimed composition is a "double ring" ACE inhibitor,

The defendants argued that the claim was obvious because it merely substituted one type of ACE inhibitor for another.

At trial, the defendants' expert acknowledged that the art had not suggested using a double ring ACE inhibitor in combination with a calcium antagonist but opined that the number of rings in the ACE inhibitor was unimportant to the analysis. Of course, the plaintiffs' expert disagreed, opining that those of ordinary skill in the art generally believed that the double ring compounds were not more effective than the single ring compounds because the single ring compounds fit into the "pocket" of the ACE inhibitors better than the double ring compounds. Furthermore, the plaintiffs' expert opined that combination treatments were not favored at the time of the invention.

At trial, the defendants' expert acknowledged that the art had not suggested using a double ring ACE inhibitor in combination with a calcium antagonist but opined that the number of rings in the ACE inhibitor was unimportant to the analysis. Of course, the plaintiffs' expert disagreed, opining that those of ordinary skill in the art generally believed that the double ring compounds were not more effective than the single ring compounds because the single ring compounds fit into the "pocket" of the ACE inhibitors better than the double ring compounds. Furthermore, the plaintiffs' expert opined that combination treatments were not favored at the time of the invention.

Although there were these disagreements, what was not in dispute was that the advantages provided by the claimed combination were real and not present in, nor predicted or suggest by, the prior art.

The defendants argued that, given the prior art teaching of combinations of ACE inhibitors and calcium antagonists, (1) claim 3 was unpatentable as a matter of law because it would have been "obvious to try" other combinations of agents, and (2) because the claim was unpatentable as a matter of law, the fact that the combination was later shown to have unexpectedly advantageous properties was irrelevant. This is where the Court's opinion gets interesting.

The Court rejected the defendants' arguments. The Court first noted that the "obvious to try" standard is qualified and applicable only when "there are a finite number of identified, predictable solutions" to a known problem. This "finite number" language is frequently encountered as a basis for rejecting chemical compound claims as obvious modifications of prior art compounds and appears often to be used merely in contradistinction to "infinite." But the Court reiterated its opinion in Ortho-McNeil Pharm., Inc. v. Mylan Labs., Inc., 520 F. 3d 1358, 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2008), where it stated that "finite" means that the number of options is small in the context of the art and easily traversed. Elaborating on "easily traversed," the Court cited In re O’Farrell, 853 F.2d 894, 903 (Fed. Cir. 1988), for the proposition that a claim is not "obvious to try" (and therefore obvious) where "the prior art gave either no indication of which parameters were critical or no direction as to which of many possible choices is likely to be successful."

The Court also rejected the defendants' argument that the later-discovered unexpected advantages of the claimed composition cannot be considered in an obviousness analysis. Referring to prior Federal Circuit case law and distinguishing case law cited by the defendants, the Court stated, "patentability may consider all of the characteristics possessed by the claimed invention, whenever those characteristics become manifest."

As this was an appeal from a jury verdict, the Court did not give its opinion as to application of the law to the facts, i.e., whether under the facts of the case there were a finite number of identified, predictable solutions to a known problem or even whether the (undisputed) unexpected advantages of the claimed composition were sufficient to render the composition obvious. Rather, the Court finally merely held that the jury could have reasonably found that the art "would not have predicted the longer-lasting hypertension control demonstrated by the double-ring structures of quinapril and trandolapril in combination with calcium antagonists, because of the widespread belief that double-ring inhibitors would not fit the pocket structure of the ACE." But if this is the sole and sufficient basis of non-obviousness, this holding is consistent with the proposition dating back at least to In re Papesch that an otherwise obvious invention is rendered non-obvious by unexpected properties.

Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH v. Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2014)

Panel: Circuit Judges Newman, Linn, and Wallach

Opinion by Circuit Judge Newman