Blocking funding for gas energy projects in Africa may seem like sensible climate policy. But is it?

Although the generally accepted ultimate goal is to replace fossil fuels entirely, there is a strong case for starting by replacing coal with natural gas, especially for baseload-generating capacity.

Finding alternatives to fossil fuels is one of the most pressing environmental priorities of the 21st century. Despite national commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over the coming decades, some scientists predict that the world will remain on a trajectory to warm up by 3 to 4 degrees Celsius by the year 2100.1 The consequences of this would be dire. According to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, rising sea levels would likely inundate low-lying coastal areas, including cities; desertification would likely destroy agricultural production and render vast temperate regions of the planet—including much of Africa—functionally uninhabitable; and extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and typhoons, could become more frequent and more intense.2

As the world aims for a cleaner energy future, the right environmental policy might seem to be to decline to fund new gas-fired power plants, gas pipelines or gas-based industries in Africa.

But could that actually hinder Africa's development and its move toward renewable technology?

Gas as a bridge between coal and renewable energy

Renewable energy currently accounts for roughly a quarter of new power generation worldwide, but it still lags behind new coal-fired capacity.3 Although the generally accepted ultimate goal is to replace fossil fuels entirely, there is a strong case for starting by replacing coal with natural gas, especially for baseload-generating capacity.

This is especially true in Africa's developing economies that need to grow their generation capacity—and face a choice between coal and gas. Gas-fired generation does emit GHGs, and investments in gas-fired generation capacity may divert or delay investments in renewable energy projects.

So, is the best path to net-zero simply to ban new GHG-emitting generation capacity and focus exclusively on renewable sources instead?

Burning gas generates fewer local pollutants (SOX, NOX and particulates) than coal and roughly half as much CO2 per unit of energy (see Figure 1). Thus, policy and economic conditions that allow accelerated retirement of coal-fired power plants and their replacement with gas-fired plants could still yield significant reductions in GHG emissions.

View full image: Figure 1. Natural gas generates approximately half as many CO2 emissions per unit energy as coal (PDF)

Although Africa is blessed with huge potential for solar and wind power generation, the continent currently accounts for less than 1 percent of global solar power generation. In semi-arid rural areas of Southern Africa, solar photovoltaic generation offers particular promise as a renewable energy source.

Yet solar and wind power rely on the sun shining and the wind blowing. African nations that are growing their renewable capacity still face challenges managing the intermittent availability of sunshine and wind. In addition, many of them lack available storage technologies to materially increase these power supplies without new investments in gas or other reliable back-up sources.

Africa's rapid urbanization means the greatest demand for electricity comes from cities, where space constraints can make it difficult to install new solar and wind turbine facilities. Finally, most national and regional transmission and distribution grids were developed around central generation nodes. While these might be redeveloped over the course of a century to accommodate more local renewable energy facilities, it would be difficult to implement this as a short- or even medium-term solution.

In Africa particularly, a quest for "net-zero" emissions must balance with development priorities

4%

of global electricity is consumed by Africa, which is home to almost a fifth of the world’s population.

Source: The Economist

Energy transition in much of sub-Saharan Africa is less about moving to renewables than about providing electricity where currently none exists. During the last decade, a larger share of the world's population gained access to electricity than ever before—except in sub-Saharan Africa, where it actually decreased.5

Although Africa is home to almost a fifth of the world's population, it accounts for only 4 percent of global electricity consumption. While electricity is nearly universal across North Africa, fewer than half of sub-Saharan Africans can access electricity.6

Therefore, African policy-makers face a challenging dilemma: Bridging Africa's energy deficit is crucial to the economic well-being of the continent and its people. Yet the impacts of climate change are likely to fall more heavily on Africa than other global regions.

Along with leaders in other emerging markets, African policy-makers argue that since wealthy, industrialized countries became prosperous through fossil fuel emissions, these countries should lead the way in reducing their GHG emissions to offset the impact of the developing world's quest for economic growth and greater prosperity. In addition, these countries should provide technology transfers and financial support necessary to help grow Africa's clean generation capacity.

With the exception of South Africa (and its fleet of coal-fired power stations), Africa's contribution to GHG emissions has historically been negligible. As recently as 2019, the continent accounted for less than 4 percent of global GHG emissions.7 While this may increase over time, it will very likely remain less than Europe, North America and Asia-Pacific. Measured by CO2 emissions per capita, the difference between Africa's contribution to climate change and that of other regions and countries is stark (see Figure 2)8.

View full image: Figure 2. Compared to other regions and countries, Africa's GHG emissions are modest (PDF)

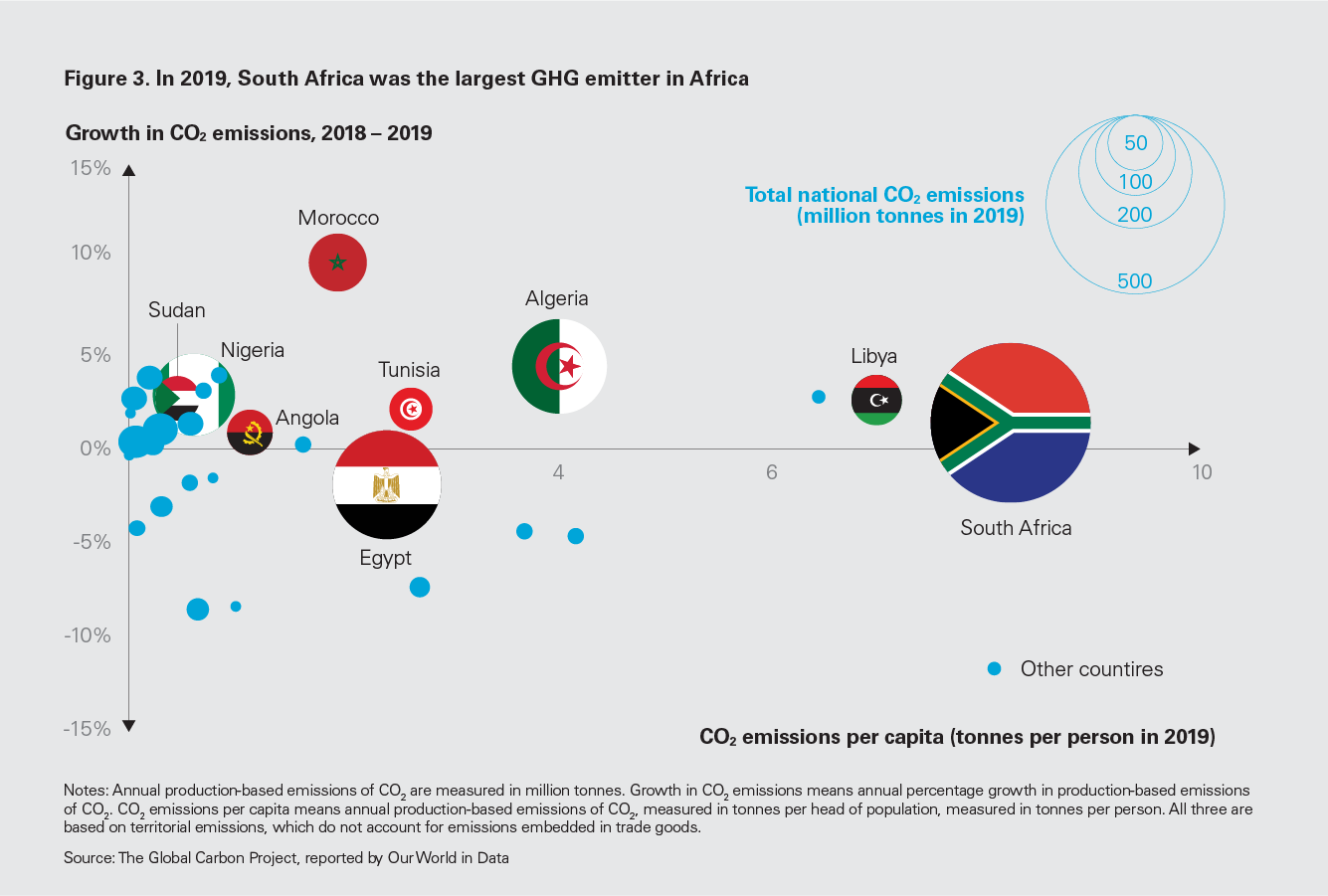

Within Africa, South Africa is the largest GHG emitter (see Figure 3). When its new coal-fired Kusile and Medupi power stations finally become fully operational, they will further increase this load.9 In addition, South Africa's fleet of coal-fired power stations are aging, with all but three of them now more than 30 years old (see Figure 4).

South Africa's utility Eskom intends to shut down more than 20 percent of its current coal-fired generation capacity by 2030 and most of the remainder by 2050,10 and replace that capacity with renewable energy sources. However, the amount of reliable baseload required to sustain the southern African economies that rely on Eskom for power could make gas an attractive option—at least as a bridging technology if battery and hydrogen technologies do not become available at the required scale over this timeframe.

View full image: Figure 3. In 2019, South Africa was the largest GHG emitter in Africa (PDF)

A wealth of potential

Africa's gas reserves are underexplored, but proven gas reserves should be sufficient to produce enough electricity to transform the continent.

Africa lacks the extensive transmission and distribution networks of Europe and North America, but it is expanding its existing networks (see Figure 5).

To minimize Africa's future GHG emissions, the countries with access to gas must prioritize it over coal or oil—while they simultaneously develop non-GHG-emitting solutions—and expand the continent's gas transmission network. While sub-Saharan African countries expect to have 60 million tonnes per year (mt/year) of export capacity of LNG by 2025 and a further 74 mt/year by 2030,11 they also expect to increase their own use of natural gas through gas-to-power projects.

View full image: Figure 5. Africa's power lines (existing and planned) and natural gas reserves (PDF)

Conclusion

The pathway to limiting global warming requires ceasing all GHG-emitting power generation. This might be feasible over the long term. Yet with major GHG-emitting countries in the developed world proving slow to reduce their own emissions, it is unfair to expect that Africa's leaders will subjugate their own socio-economic development to the world's need to eliminate GHGs.

In regions of Africa where both coal and gas are available, technology transfer and funding can be used as levers that encourage the use of gas over coal. Coupled with the development of an Africa-wide power transmission and distribution network, along with aggressive expansion of renewable energy sources and other non-GHG emitting generation, this could reduce Africa's future impact on climate change while allowing Africa's economies to develop and transform the quality of life for their people.

1 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01125-x

2 UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2022 at https://www.ipcc.ch

3 The role of gas in today's energy transitions, IEA 2019 at https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-gas-in-todays-energy-transitions

4 https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/co2_vol_mass.php

5 World Bank, 2021 at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/06/07/report-universal-access-to-sustainable-energy-will-remain-elusive-without-addressing-inequalities

6 The Economist, 2019 at https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/11/13/more-than-half-of-sub-saharan-africans-lack-access-to-electricity

7 United Nations, 2021 at https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/july-2021/cop26-climate-top-priorities-africa

8 Global Carbon Project at https://www.globalcarbonproject.org

9 https://www.gem.wiki/Kusile_Power_Station; https://www.gem.wiki/Medupi_Power_Station

10 https://renewablesnow.com/news/eskom-looking-to-renewables-as-s-africa-is-reducing-coal-power-751345/

11 S&P Global, 2021 at https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/020921-sub-saharan-africa-could-green-light-74-mil-mtyear-lng-capacity-by-2030-acting

[View source.]