Business Method Patent Survives PTAB Review

On January 22, 2016, the U.S. Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) issued a decision denying institution of a covered business method (CBM) patent review in a case captioned NRT Technology Corp. and NRT Technologies, Inc. (Petitioner) v. Everi Payments, Inc. (Patent Owner) (Case CBM2015-00167; U.S. Patent No. 6,081,792).

The PTAB determined that that Petitioner was less likely than not to prevail with respect to all of the challenged claims, and thus, the Petition to institute a CBM patent review was denied. This is a good sign for business method patent owners to show that business method patents are not outright dead. There is hope, if the claims are properly drafted.

The PTAB first noted the requirements for instituting a CBM patent review in that the Director must determine "that the information presented in the petition . . . would demonstrate that it is more likely than not that at least 1 of the claims challenged in the petition is unpatentable." 35 U.S.C. § 324(a). The threshold for instituting petitions for post grant reviews -- codified at 35 U.S.C. § 324(a) -- also applies to petitions for CBM patent reviews. The difference, of course, for a CBM patent review is that the claims challenged must be directed to a financial product or service (and thus, excludes technological inventions), and the Petitioner must be charged with infringement of the patent in order to request a CBM patent review. Prior to addressing the issue of standing, it is necessary to investigate the scope of the '792 patent.

The '792 patent subject matter

The '792 patent describes an interesting function for use of automated teller machines ("ATMs") to issue receipts for a "purchase" that can be cashed in at designated locations for cash of the purchase.

The '792 patent relates to a modified ATM or terminal that allows a customer to obtain cash from an account via various processes such as an ATM process or a point-of-sale ("POS") process using both debit cards and credit cards. In its "Description of the Prior Art," the '792 patent notes two so-called problems associated with obtaining cash from prior art ATMs (i.e., via an ATM network). First, with respect to using a debit/ATM card, a bank typically imposes a daily limit on ATM cash withdrawals. Second, with respect to using a credit card to obtain cash from an ATM, the '792 patent blames people for often not knowing the personal identification number ("PIN") that is required because they may not regularly use a credit card for that purpose.

According to the '792 patent, neither of these problems is encountered when using the same cards to make purchases, which occur over a POS network, not an ATM network. With respect to debit/ATM cards, "one can reach [his] ATM limit and not be able to obtain more cash that day from an ATM, but will still be able to purchase goods and services via a point-of sale transaction because of the distinct and separate limit for point-of-sale transactions." With respect to credit cards, the '792 patent states that PINs are not typically required to make purchases. (However, while not described in the '792 patent, as credit cards change over to the Chip-enabled technology, many credit card companies are requiring use of PINs).

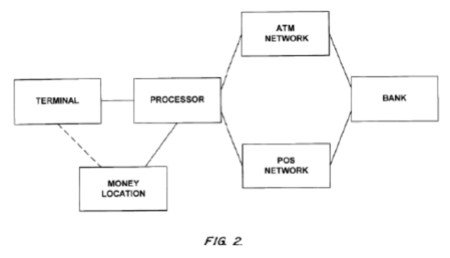

The '792 patent describes and claims methods of using a modified ATM or terminal that can access a bank via both an ATM network and a POS network. Figure 2 is reproduced below.

The '792 patent describes a method of using a modified ATM such as the terminal depicted in Figure 2, in which a cardholder first attempts to obtain money via a first type of transaction (i.e., conducted over an ATM network) and fails because he has exceeded his ATM daily limit or he cannot remember the PIN for his credit card and subsequently and successfully obtains money via a second type of transaction (i.e., conducted via a POS network).

But, the cardholder does not obtain cash (or other valuable item) directly from the terminal when using the POS network. Instead, the terminal informs a nearby money location (such as "cash windows or 'cages' within casinos or racetracks, front desks or concierges of hotels, ticket booths, will-call windows or customer service windows at stadiums, coliseums, theaters, stores, or amusement parks") of the approved transaction. The terminal may also issue a "script" or "pre-receipt" for the cardholder to take to the money location. At the money location, the cardholder cashes in the receipt for the cash. In the preferred embodiment, a check drawn against the cardholder's account is issued at the money location and made payable to the money location owner.

The challenged claims

Of the challenged claims, claim 1 is illustrative and reproduced below.

1. A method of providing money or an item of value to an account-holder, the method comprising:

identifying an account to a terminal;

entering a personal identification number into the terminal;

requesting money or an item of value based upon the account via a first type of transaction;

forwarding the first type of transaction to a processor;

forwarding the first type of transaction from the processor to a first network;

forwarding the first type of transaction from the first network to a bank;

making a denial of the first type of transaction due to exceeded pre-set limit;

forwarding the denial to the processor;

notifying the account-holder at the terminal of the denial of the first type of transaction, and asking the account holder if they would like to request the money or item of value via a second type of transaction;

requesting money or an item of value based upon the account via a second type of transaction;

forwarding the second type of transaction to the processor;

forwarding the second type of transaction from the processor to a second network;

forwarding the second type of transaction from the second network to the bank;

making an approval of the second type of transaction;

forwarding the approval to the processor;

and instructing a money location separate from the terminal to provide money or an item of value to the account-holder.

In a CBM patent review, the PTAB noted that "[a] claim in an unexpired patent shall be given its broadest reasonable construction in light of the specification of the patent in which it appears." While the Petitioner proposed express constructions, many of which would require, or at least encompass, human involvement in certain steps of the claimed methods, the PTAB agreed with the Patent Owner that the plain and ordinary meaning is readily apparent.

Petitioner has standing

The PTAB addressed the issue of standing, noting that Petitioner has shown that the (1) Petitioner has been sued for infringement of the patent and (2) the patent for which review is sought is a covered business method patent.

With respect to item (2), a CBM patent is defined as "a patent that claims a method or corresponding apparatus for performing data processing or other operations used in the practice, administration, or management of a financial product or service, except that the term does not include patents for technological inventions." This requirement has two prongs: (i) that all of the claims are directed to methods used in conducting financial transactions and (i) that the patent is not for a technological invention.

To determine whether a patent is for a technological invention, the PTAB considers "whether the claimed subject matter as a whole": (1) "recites a technological feature that is novel and unobvious over the prior art"; and (2) "solves a technical problem using a technical solution." 37 C.F.R. § 42.301(b).

The Petitioner argued that "all of the claimed features that could possibly be characterized as technological (i.e., terminal, processor, ATM network, POS network) were present in the prior art." The Patent Owner disputed this position, and asserted that the software had a technological feature of "asking the account holder if they would like to request the money or item of value via a second type of transaction." But, the PTAB found that displaying declaratory and interrogatory data on a display and soliciting a response thereto is not a technological feature that is novel.

Further, the PTAB noted that the problem in the prior art which the '792 patent sets out to solve -- "obtaining cash from one's account when their daily ATM limit has been reached" -- is not a technical problem. Thus, the PTAB found that the '792 patent is a covered business method patent that is eligible for CBM patent review.

Patent-ineligibility

The Petitioner challenged the claims as patent-ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101. The PTAB noted the Supreme Court's framework for distinguishing patents that claim laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas from those that claim patent-eligible applications of those concepts. First, it is determined whether the claims at issue are directed to one of those patent-ineligible concepts. If so, we then ask, "what else is there in the claims before us?" This second step has become known as a search for an inventive concept -- i.e., an element or combination of elements that is sufficient to ensure that the patent in practice amounts to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.

The Petitioner did not identify directly "the abstract ideas" to which the claims are purportedly directed. But, the Petitioner implicitly identified them as: "providing money to an account holder" and "trial-and-error."

The PTAB found that the Petitioner oversimplified the challenged claims because the challenged claims are not directed simply to the idea of providing money to an account holder or using trial-and-error until success is achieved. Rather, the claims are directed to particular methods of providing money to an account holder using an ATM via a POS transaction after an ATM transaction has failed.

Further, Petitioner's analysis omits any consideration of the elements of the claims as ordered combinations to determine whether the additional elements transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application. The PTAB found that it was Petitioner's burden to do so. Failing to meet this burden, the Petitioner was unable to show that the claims are more likely than not patent-ineligible.

Other grounds asserted in the Petition included prior art challenges, which also failed and are not discussed in detail here. Because the information presented in the Petition did not demonstrate that it is more likely than not that any of the claims challenged is unpatentable, the Petition for instituting a CBM patent review was denied and no trial will be instituted.

This decision represents a rare instance in which a patent found to be directed to a "business method" was also found to satisfy § 101, at least with respect to the basic challenges presented. It may be the case that the Petitioner did not prepare a solid challenge, and likely did not do itself any favors by failing to directly identify "the abstract ideas" in the claims. However, on their face, the claims appear to recite enough details to withstand a § 101 challenge.

This case also shows, what is seeming to become the best way to counter a § 101 challenge, that when the elements of the claims are considered as ordered combinations, there is a better chance to show that the "additional elements" not identified as the abstract idea transform the nature of the claims into a patent-eligible application. This idea of ordered combinations of the elements makes it clear that when the claim is drafted tying each element together or showing that a subsequent element depends upon outcomes of a prior element, it is more difficult to pick apart the claim in a piecemeal manner. Following, it is more difficult to identify and remove a so-called "abstract idea" from the claim leaving only wreckage that is insubstantial generic computing components that are always found to fail the inventive concept test. Thus, using proper claim drafting techniques, "ordered combinations" of elements are a great tool to have to combat a § 101 challenge.