The Department of Health and Human Services has released extensive and significant revised final rules governing the Physician Self-Referral Law1 (the Stark law) and the Medicare Anti-Kickback Statute2 (AKS) in furtherance of its efforts to create a more hospitable regulatory climate for innovation in health care. The regulations are part of the HHS Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care and have the stated goal of removing regulatory barriers to coordinated care and value-based care in order to permit innovation designed to improve quality of care, health outcomes and efficiency in our health care system.

The final rules went on display at the Federal Register on November 20, 2020 and were officially published in the Federal Register on December 2, 2020. The final regulations, which were issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), considered comments received in response to proposed rules published in October 2019. Both final rules are effective on January 19, 2021, with the exception of certain changes to the physician self-referral group practice compensation distribution provisions, which were delayed until January 1, 2022.

The new exceptions and safe harbors for value-based arrangements were developed with the goal of removing regulatory barriers and creating flexibility for industry-led innovation in the delivery of better and more efficient coordinated health care for patients and improved health outcomes while supporting the Secretary's priorities and the trend toward adoption of value-based reimbursement models in the health care industry. These exceptions and safe harbors are meant to provide incentives to move toward non-fee-for-service payment models while also ensuring strong program integrity safeguards are in place to prevent the potential risks of value-based models such as stinting on care (underutilization), cherry-picking (choosing to care for more valuable patients), lemon-dropping (denying care to undesirable patients), and the manipulation or falsification of data used to verify outcomes.

Overarching Value-Based Framework

CMS and OIG clearly worked together in considering comments and developing these final rules. Nonetheless, differences remain between the regulations, notwithstanding the fact that both CMS and OIG acknowledged that they received comments requesting that the final regulations mirror each other as much as possible.

CMS and OIG underscored in the preambles to the final regulations that, while they have coordinated with respect to the exceptions and safe harbors for value-based arrangements, they are deliberately distinct in a number of aspects. This is because the underlying statutes have different constructs and associated penalties. The safe harbors are intended to provide protection under the Anti-Kickback Statute, which is an intent-based criminal statute. In contrast, the Stark law is a strict liability statute such that a DHS entity and a physician involved in a value-based arrangement must meet an exception in order to have referrals between those entities, regardless of intent.

The final regulations include intentional differences that allow the AKS to "provide 'backstop' protection for Federal health care programs and beneficiaries against abusive arrangements that involve the exchange of remuneration intended to induce or reward referrals under arrangements that could potentially satisfy the requirements of an exception to the Stark law."3 In this respect, the final rules work to balance each other and permit parties with arrangements that are subject to both laws to develop and implement value-based arrangements that avoid the strict liability referral and billing prohibitions of the Stark law, while ensuring that law enforcement, including OIG, can take action against parties engaging in intentional pay-for-referral schemes.

Value-Based Definitions

While the exceptions and safe harbors differ, CMS and the OIG aligned most of the primary definitions. The new exceptions and definitions work together to form the framework to allow value-based arrangements to function and succeed while being protected from the broad applications of the Stark law and AKS that may have previously inhibited health care innovation and the transition from fee-for-service to value-based care. The following definitions are applicable to both the CMS exceptions and the OIG safe harbors for value-based arrangements.

A value-based enterprise (VBE) is defined to mean two or more VBE participants that are parties to a value-based arrangement that are collaborating to achieve at least one value-based purpose. The VBE must also be subject to an accountable body or person, and have a governing document that describes the VBE and how it intends to achieve its value-based purpose(s).

The accountable body can be a governing board, committee, corporate officer, or participant within the value-based arrangement who is responsible for VBE oversight. The governing document sets forth the groundwork for the value-based enterprise.

A value-based arrangement is an arrangement between 1) a value-based enterprise and one or more of its VBE participants; or 2) among several VBE participants in the same value-based enterprise for the provision of at least one value-based activity for the target patient population.

The target patient population must be an identified patient population selected by a VBE or VBE participants based on legitimate and verifiable criteria that: (1) are set out in writing in advance of the commencement of the value-based arrangement; and (2) further the value-based enterprise's value-based purpose(s). As examples, "legitimate and verifiable criteria" used to identify the target patient population can include medical and health characteristics (e.g., patients receiving knee replacements); or can be based on other characteristics such as being members of a particular insurance plan or residing in a particular ZIP code. Under most circumstances, it would not be permissible to identify the patient population by selecting particularly wealthy or adherent patients (cherry-picking), or avoiding costly or non-compliant patients (lemon-dropping). In these instances, the selection criteria would not be considered legitimate even if verifiable.

A value-based activity is the provision of an item or service, or the taking or refraining from taking an action, provided the activity is reasonably designed to achieve at least one value-based purpose of the value-based enterprise. The OIG final regulations expressly state that "the making of a referral" is not a value-based activity. After considering comments, CMS decided not to finalize a proposal to exclude "the making of a referral from the definition of "value-based activity." CMS explained that it did not intend to exclude the development of a care plan that includes the furnishing of designated health services from the definition of "value-based activity." By not finalizing this exclusion, CMS is allowing care planning activities that meet the definition of "referral" at § 411.351 to qualify as "the taking of an action" to fall under the definition of "value-based activity." At the same time, CMS revised the definition of "referral" at § 411.351 to codify its policy that a referral is not an item or service for purposes of the Stark law.

Central to the definition of value-based activity is that it must drive toward a value-based purpose, which can be any of the following:

1. Coordinating and managing the care of a target patient population;

2. Improving the quality of care for a target patient population;

3. Appropriately reducing the costs to, or growth in expenditures of, payors without reducing the quality of care for a target patient population; or

4. Transitioning from health care delivery and payment mechanisms based on the volume of items and services provided to mechanisms based on the quality of care and control of costs of care for a target patient population.

Each of the options above underscore that improving care management or quality must be integral to the value-based purpose. Therefore, parties may not rely solely on reduction of cost as the value-based purpose.

There is no requirement that the value-based purpose be achieved for the arrangement to be protected, but if the parties are aware that an action, or the provision of item or service, will not further the intended value-based purposes of the arrangement, it will no longer qualify as a value-based activity. When the parties reach such a conclusion, they must amend or terminate the arrangement, as discussed further below.

VBE participants are defined to include a person or entity that engages in at least one value-based activity as part of a value-based enterprise. The OIG definition specifically excludes a "patient acting in their capacity as patient" from the definition.

In the proposed rule the OIG proposed to explicitly exclude certain entities including pharmaceutical manufacturers, PBMs, laboratories, DME suppliers and medical device distributors and wholesalers from being VBE participants. In the final rule, the OIG modified this position such that these entities are no longer excluded as value-based participants. But, while they can participate in a VBE, any remuneration exchanged involving these entities would not be protected under the safe harbor. As a result, there is some risk of including these entities as VBE participants even though it is permissible to do so. The OIG also created a pathway for certain "limited technology participants" that would otherwise be excluded from safe harbor protection to be protected under the Care Coordination Arrangements safe harbor if certain conditions are satisfied, as explained in more detail below.

CMS Exceptions

To fall under CMS's new exceptions for value-based arrangements, the parties to the arrangement must include an entity and a physician (otherwise, the Stark law's prohibitions would not be implicated). Also, because the exceptions at final § 411.357(aa) apply only to compensation arrangements, the value-based arrangement must be a compensation arrangement and not an ownership interest. CMS notes that existing value-based arrangements that already comply with an exception are not required to use one of the new exceptions. As long as the arrangement satisfies all elements of any applicable exception, the arrangement is permitted under the Stark law.

CMS's § 411.357(aa) exceptions do not require that compensation be set in advance, consistent with fair market value, or determined in a manner that does not take into account the volume or value of the physician's referrals or other business generated by the physician. Instead, all three of CMS's value-based exceptions require that the remuneration must be for, or result from, value-based activities undertaken by the recipient of the remuneration for patients in the target population. Therefore, the final exceptions will not protect payments, referrals, or other actions unrelated to the target population including general marketing or sales arrangements. If the remuneration is in-kind, it must be necessary and may not simply duplicate technology or infrastructure that is already owned by the recipient.

CMS recognizes that in gainsharing, shared savings, and other value-based arrangements, there may not necessarily be a one-to-one payment based on the value-based activities, but the value-based activities and their value-based purpose need to be foundational to the exchange of remuneration. In all instances, CMS requires that the remuneration cannot be for an inducement to reduce or limit medically necessary services. The CMS exceptions also do not permit "swapping" by conditioning VBE participation or the remuneration exchanged through the value-based arrangement on the referral of patients that are not part of that targeted population or business that is not otherwise covered by the value-based arrangement. Recognizing the importance of protecting patient choice, the final regulations specify that, if the remuneration paid to the physician is conditioned on referrals to a particular provider, practitioner or supplier, this requirement must be set out in writing and signed by the parties. Additionally, such a referral requirement may not apply if the patient expresses preference for another provider, practitioner, or supplier; the patient's insurer makes the determination; or the referral is not in the patient's best medical interest in the physician's judgment.

The CMS exceptions apply regardless of whether the arrangement includes care furnished to Medicare beneficiaries, non-Medicare patients, or a combination of both. For all of the value-based arrangement exceptions, records of the methodology for determining and the actual amount of remuneration paid under the value-based arrangement must be maintained for a period of at least six years and made available to the Secretary upon request.

Full Financial Risk (§ 411.357(aa)(1))

The Full Financial Risk exception applies to value-based arrangements between VBE participants in a value-based enterprise that has assumed "full financial risk" on a prospective basis for the cost of all patient care items and services covered by the applicable payor for each patient in the target patient population for the entire term of the arrangement. This would include, for example, capitation payments or global budget payments from a payor. The final rule makes clear that the exception is not limited in application to only these approaches listed in the regulation.

This exception is also available to protect value-based arrangements entered into in preparation for the implementation of the value-based enterprise's full financial risk payor contract where such arrangements begin after the value-based enterprise is contractually obligated to assume full financial risk for the cost of patient care. In the final rule, CMS extends this protection from six months to 12 months for the transition period. The exception does not require a writing, but CMS advises that it is good business practice to reduce to writing any arrangement between referral sources to ensure the arrangement can be monitored. Protected remuneration can be monetary or in kind as long as it results from value-based activities undertaken by the recipient for the patients in the target population.

Meaningful Downside Financial Risk to the Physician (§411.357(aa)(2))

The Value-Based Arrangements with Meaningful Downside Financial Risk to the Physician exception protects remuneration paid under a value-based arrangement where the physician is at meaningful downside financial risk for failure to achieve the value-based purpose(s) of the value-based enterprise. Previously, CMS proposed to define "meaningful downside financial risk" as where a physician is responsible to pay the entity no less than 25 percent of the value of the remuneration the physician receives under the value-based arrangement. In response to comments, CMS reconsidered this threshold. Physicians now will qualify for the exception where at least 10 percent of the total value of the remuneration the physician receives under the value-based arrangement is at risk. The required amount of risk was reduced to encourage physician participation, recognizing that many physicians may not be prepared to take on 25 percent of risk associated with the payments. Under this exception, the nature and extent of the physician's downside financial risk must be set forth in writing, but there is no signature requirement. This exception applies to both monetary and in-kind remuneration, and the remuneration can be for any value-based purpose included in the definition above.

CMS clarified that it intended the meaningful downside financial risk exception not be completely aligned with the OIG Substantial Downside Financial Risk safe harbor. This is because the focus of the exception is on the risk assumed by the individual physician to the value-based arrangement, whereas the safe harbor focuses on the required financial risk that the VBE (directly or through its participants) must assume for the safe harbor to be available. Thus, the exception and the safe harbor are inherently different.

Value-Based Arrangements (§411.357(aa)(3))

The Value-Based Arrangements exception applies to compensation arrangements that qualify as value-based arrangements, regardless of the level of risk undertaken by the value-based enterprise or any of its VBE participants. Because the parties undertake less risk, this exception has additional safeguards. The safeguards include the requirement of a signed writing (not required by the two other value-based exceptions), as well as annual monitoring requirements to track the value-based activities and related impact and progress of such activities. Value-based arrangements without financial risk are required to be commercially reasonable. (See below for a further discussion of the definition of "commercially reasonable.") In an important departure from the OIG safe harbor for coordinated care arrangements which only applies to in-kind remuneration, the CMS exception applies to both monetary and non-monetary remuneration. The methodology for determining remuneration must be set in advance.

With respect to the signed writing, the final regulations specify that it must include a description of the value based activities to be undertaken, how they are expected to further the purposes of the value-based enterprise, the target population, the type or nature of remuneration, the methodology used to determine the remuneration, and outcome measures against which the recipient of the remuneration is assessed, if any.

Under this exception, outcome measures are optional since CMS has recognized that they may not be applicable to all value-based arrangements. As an example, an arrangement under which a hospital provides necessary infrastructure to a physician in the same value-based enterprise may not require the physician to meet specific outcome measures to receive or maintain the infrastructure items or services. To the extent outcome measures are used to evaluate value-based arrangements, they are defined as a benchmark that quantifies: (A) improvements in or maintenance of the quality of patient care; or (B) reductions in the costs to or growth of expenditures of payors while maintaining or improving the quality of patient care. Only outcome measures that are objective, measurable, and selected based on clinical evidence or credible medical support should be used to assess whether a recipient is entitled to remuneration in a value-based arrangement. Any changes to the outcome measures must be made only prospectively and set forth in writing.

While CMS does not prescribe exactly how value-based enterprises, entities, and physicians should monitor their value-based arrangements, VBEs are expected to design their monitoring and other compliance efforts in a manner that is appropriate for the particular value-based arrangement. On an annual basis, or at least once during the term of arrangements lasting less than one year, the value-based enterprise or its parties must monitor (1) whether the parties have furnished the value-based activities required under the arrangement; (2) whether and how the continuation of the value-based activities is expected to further the value-based purpose(s) of the arrangement, and the progress toward attainment of outcome measure(s), if any, against which the recipient of remuneration is assessed.

If monitoring indicates that a value-based activity is ineffective at furthering the purposes of the value-based enterprise, the arrangement must be terminated within 30 consecutive calendar days after completion of the monitoring, or the parties must modify the arrangement within 90 days to terminate the ineffective value-based activity. When monitoring determines that an outcome measure is unattainable during the remaining term of the arrangement, the outcome measure must be terminated or replaced within 90 consecutive calendar days after completion of the monitoring.

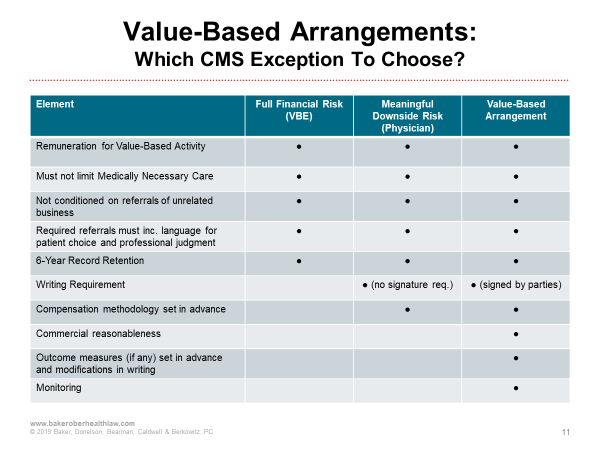

The following chart compares the elements of CMS's value-based exceptions. This will assist in evaluating arrangements to determine which exception is appropriate and the related requirements under the applicable exception.

Indirect Compensation Arrangements to which the Exceptions at §411.357(aa) are Applicable

CMS acknowledges the challenges that could arise related to certain indirect compensation arrangements that include a value-based arrangement in the unbroken chain of financial relationships. Previously, the only exception available for protection under the Stark law was the indirect compensation exception at §411.357(p). In the final rule, CMS determined at §411.354(c)(4)(iii) that the value-based exceptions are available to protect the physician's referrals to the entity when an indirect compensation arrangement includes a value-based arrangement to which the physician (or the physician organization in whose shoes the physician stands) is a direct party. In order for these exceptions to be applicable, the link closest to the physician may not be an ownership interest; it must be a compensation arrangement that meets the definition of value-based arrangement. This is a beneficial change that permits certain value-based arrangements that could not otherwise satisfy the indirect compensation exception at §411.357(p) (or a direct compensation exception) to consider analysis under the less restrictive value-based exceptions.

To clarify a potential source of confusion, CMS also finalized regulations at 411.354(c)(4)(ii) and (iii)(B) to expressly state that the exception for risk-sharing arrangements at §411.357(n) is only applicable in the case of an indirect compensation arrangement in which the entity furnishing designated health services is a MCO or IPA. Stated another way, if the entity with which the physician has an indirect compensation arrangement is not an MCO or IPA, the exception for risk-sharing arrangements is not applicable to the indirect compensation arrangement. Accordingly, the exception for risk-sharing arrangements does not apply to indirect compensation arrangements between hospitals and physicians, even if both are contractors or subcontractors to the same MCO or IPA.

OIG Safe Harbors

Like CMS, the OIG's new safe harbors and definitions for value-based arrangements are designed to further the goals of access, quality, patient choice, appropriate utilization, and competition, while protecting against increased costs, inappropriate steering of patients, and harms associated with inappropriate incentives tied to referrals. The OIG worked to balance the competing challenges of the flexibility needed for change and innovation with the safeguards necessary to protect Federal health care programs and patients. The OIG indicates that it endeavored to create rules that are clear, objective, flexible and easy to implement while also including adequate safeguards.

The safe harbors address a broad range of value-based arrangements for coordinated care activities. In order to offer safe harbor protection to a variety of potential arrangements, the final safe harbors vary by the types of remuneration protected (not all protect monetary remuneration), as well as by the types of entities that may rely on the safe harbors, the level of financial risk undertaken by the parties, and the required safeguards. The intent is that these safe harbors will protect both existing and emerging value-based arrangements.

The OIG final rule includes three new safe harbors encompassing a variety of value-based arrangements. None of these safe harbors protect ownership and investment interests. Additionally, each requires that the remuneration not be exchanged for, or used for, marketing items for patient recruitment activities. That said, the OIG recognizes that patient education can be critical to care coordination for value-based care. Parties will have to carefully consider whether certain activities are patient education activities that further a value-based purpose, or whether the activities could be construed as marketing.

As explained above, even though the OIG and CMS have some notable differences in their final rules, the value-based terminology finalized for VBEs and value-based arrangements eligible for protection under a value-based safe harbor under the Anti-Kickback Statute or a value-based exception under the Stark law are aligned in nearly all respects.

Unlike CMS, however, the OIG did include restrictions on the parties eligible to be protected under the value-based safe-harbors. While these entities are not precluded from VBE participation, remuneration from the following entities is not eligible for safe harbor protection: pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, and wholesalers; pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs); laboratory companies; pharmacies that primarily compound drugs or primarily dispense compounded drugs; manufacturers of devices or medical supplies; entities or individuals that sell or rent DMEPOS (other than a pharmacy or a physician, provider, or other entity that primarily furnishes services); and medical device distributors and wholesalers. The OIG did include a separate pathway under the care coordination arrangements safe harbor that protects limited technology arrangements involving manufacturers of devices or medical supplies and DMEPOS, under specific conditions, which will be explained in more detail below.

Value-Based Arrangements with Full Financial Risk (§ 1001.952(gg))

The VBE safe harbor for value-based arrangements with full financial risk protects arrangements in which the VBE has accepted full financial risk or is obligated to accept that risk within 12 months. This safe harbor provides the greatest flexibility, as it also requires the assumption of the most risk. Full Financial Risk is defined as responsibility for all the costs of all items and services covered by a payor for each patient in the target populations for a term of one year. The remuneration protected under this safe harbor includes both monetary and in-kind remuneration from a VBE to a VBE participant.

Generally, full financial risk is going to be some sort of capitation payment or global budget payment accepted at the VBE level. This could be the VBE enterprise or it could be multiple VBE participants that have banded together to take on the financial risk. By allowing the parties to be contractually obligated to accept full financial risk within 12 months, the OIG has acknowledged and allowed safe harbor protection of some of the pre-risk period implementation costs that can be associated with value-based arrangements.

One of the key distinctions between the OIG safe harbor and CMS exception is that the CMS rule applies to remuneration between the VBE and VBE participant or among the VBE participants. This could include two VBE participants in the same value-based enterprise. In contrast, the OIG rule only applies to remuneration between the VBE and a value-based participant, but not to downstream entities. The OIG clarified in the preamble that the safe harbor could protect a value-based participant acting on behalf of the VBE, in circumstances where the VBE is not a formal legal entity, but rather is comprised of a network of VBE participants. In these cases, the safe harbor could protect the exchange of remuneration between the VBE participant acting on behalf of the VBE and other VBE participants. In contrast, the safe harbor would not protect remuneration exchanged between two VBE participants if neither of them is currently acting on behalf of the VBE.

Another aspect of the OIG full financial risk safe harbor distinct from the CMS full financial risk exception is that the OIG safe harbor requires the VBE to have a quality assurance program to protect against underutilization and assess the quality of care for the target population.

Finally, the OIG requires a signed writing for a value-based arrangement with full financial risk to be protected under the safe harbor, whereas the CMS exception does not have a writing requirement.

Value-Based Arrangements with Substantial Downside Financial Risk (1001.952(ff))

The safe harbor for value-based arrangements with substantial downside risk protects both in-kind and monetary remuneration between a VBE and a VBE participant if the VBE undertakes the requisite amount of risk. The OIG safe harbor for substantial downside risk requires both the VBE and its VBE participants to separately be at substantial risk. In contrast, the CMS exception requires only the physician to be at meaningful downside financial risk. The VBE may satisfy the OIG safe harbor financial risk requirement in various ways, including shared savings with a repayment obligation of 30 percent of any losses associated with all items and services to the target patient population or 20 percent of any losses for episodic care. This could include taking on episodic or bundled payments related to a defined set of characteristics and across at least more than one care setting. There are also some opportunities for VBEs to meet the financial risk requirement associated with this safe harbor through an arrangement with certain partial capitation payments.

The OIG substantial downside financial risk safe harbor also requires VBE Participants to "meaningfully share" in downside risk. In the proposed rule, participants would have had to undertake risk of at least 8 percent of the amount for which the VBE is at risk. In response to comments, the OIG final rule requires VBE participants to share in at least 5 percent of the losses in savings realized by the VBE, or be at risk for a per-patient payment for a predefined set of items and services (partial capitation).

Unlike the parallel CMS exception, which allows the remuneration to be for any of the four value-based purposes, the OIG safe harbor requires remuneration to be related to one or more of the following value-based purposes: (1) coordinating and managing the care of a target patient population; (2) improving the quality of care for a target patient population; (3) appropriately reducing the costs to or growth in expenditures of payors without reducing the quality of care for a target patient population. Notably, the fourth value-based purpose in the definition (transitioning from volume to value) is not a purpose that can be used on its own to satisfy this safe harbor. Additionally, the writing required to satisfy the OIG safe harbor for substantial downside risk must be signed by the parties and must specify material terms such as the risk assumption by each party and the type of remuneration exchanged.

Care Coordination Arrangements to improve quality, health outcomes, and efficiency (1001.952(ee))

The care coordination arrangements safe harbor protects only non-monetary/in-kind remuneration. This safe harbor is the least flexible because, while it does not require the participants to take on risk, it does require that the arrangement be measured based on at least one evidence-based outcome measure, along with several other safeguards that ensure transparency. The exchange of in-kind remuneration is permitted under this safe harbor pursuant to value-based arrangement, where the parties establish legitimate outcome measures to advance the coordination and management of care for the target patient population. The arrangement and all value-based arrangements within the value-based enterprise must be commercially reasonable. In addition, in this safe harbor the recipient of the in-kind remuneration must share in at least 15 percent of the cost or fair market value of the remuneration.

To be protected under this safe harbor, the in-kind remuneration exchanged must be used predominantly to engage in value-based activities that are directly connected to the coordination and management of care for the target population. Additionally, the remuneration must not result in more than incidental benefits to persons who are not part of the target patient population. By using terminology that allows some flexibility for "incidental benefits" the OIG acknowledges that it may be difficult to anticipate some "spillover" benefits of value.

To explain how the "predominant use" requirement applies, the OIG provides an example of a health information technology tool that enables both remote patient monitoring and two-way telehealth capabilities that would be protected under the safe harbor if it is used to coordinate and manage care for the target population. If the same tool with the same functionalities may be used by the recipient for purposes other than coordinating and managing care for the target populations (e.g., for collecting tracking and analyzing the VBE participant's internal financial metrics for purposes of operating the VBE's business), it likely would not satisfy the predominant use requirement necessary to be protected by the safe harbor.

Another safe harbor requirement is that the remuneration exchanged will not be protected if it is used more than incidentally for the recipient's billing or financial management services, or for purposes of marketing or patient recruitment activities. The safe harbor does not prohibit all marketing and recruitment activities, but the requirements will not be satisfied if the remuneration exchanged is used for these purposes. The OIG clarified that the provision of objective patient education materials or engaging in patient informational activities does not constitute marketing or patient recruitment activities for purposes of satisfying this safe harbor condition.

The remuneration exchanged cannot (1) be conditioned on referrals from patients who are not part of the target population or other pull through business; (2) reduce medically necessary care; or, (3) be anticipated by the offeror to be diverted, resold, or used by the recipient for an unlawful purpose. Consistent with the CMS exception, the value-based arrangement will not satisfy the safe harbor if it limits any VBE participant's ability to make decisions in the best interest of its patients, and it may not direct referrals to a particular provider, practitioner or supplier if this goes against patient preference, a payor determination, or the direction or restriction of referrals is contrary to applicable law.

Unlike the CMS exception for value-based arrangements, the OIG safe harbor for care coordination agreements includes a participant cost-sharing requirement. Specifically, the Care Coordination Arrangements Safe Harbor requires that the recipient of remuneration must pay at least 15 percent of the offeror's cost for the remuneration, or the fair market value of the in-kind remuneration. This contribution must be made for one-time costs in advance of receiving the in-kind remuneration, or at regular intervals specified in writing for ongoing costs.

If parties to a value-based arrangement or various value-based arrangements are sharing in-kind remuneration provided by the VBE, the OIG has confirmed that it is permissible to make a reasonable good faith allocation of the required contribution of 15 percent of the offeror's cost or the fair market value of the resources shared by the various VBE participants.

Unlike the physician self-referral exception for value-based arrangements, which makes outcome measures optional, the OIG safe harbor for care coordination arrangements requires the parties to establish one or more legitimate outcome or process measures. The parties must reasonably anticipate that the measures selected relate to the remuneration exchanged under the value-based arrangement and will advance the coordination and management of care for the target patient population based on clinical evidence or other medical or scientific support (instead of relying solely on patient satisfaction or convenience). The OIG has advised that using measures validated by a credible third party would be prudent but is not required. One or more of the benchmarks selected should be related to improving coordination and management of care for the target population. While there is not a specific timeframe required for review, the benchmark(s) should be periodically assessed to ensure they continue to meet their intended purpose. The parties must include a description of the outcome or process measures in a signed writing that is made available to the HHS Secretary.

By finalizing a requirement that the outcome or process measures must be legitimate and reasonably anticipated to achieve their purpose, instead of requiring the use of evidence-based or industry standard measures, the OIG provides more flexibility with respect to the measures that may be selected. Additionally, the OIG has permitted the measures to be "process based," which could include, as an example, a measurement of the number of patients with diabetes who had their blood pressure tested. Parties may select measures applicable to the entire target population, or they may select different measures for different segments of the target population. The final rule provides an example where it would be permissible for parties to select one measure for organ transplant patients within the target population and a different measure for non-transplant patients.

The terms of the value-based arrangement must be set forth in writing and signed by the parties in advance of, or contemporaneous with the commencement of the arrangement, or any material change thereto. At a minimum, this writing should address the following key elements of the value-based arrangement, including the value-based purposes; the value-based activities undertaken; the term; the target population; a description of the remuneration, either the offeror's cost for the remuneration and the reasonable accounting methodology used by the offeror to determine its cost, or the fair market value of the remuneration; the percentage and amount contributed by the recipient; the frequency of the recipient's contribution payments for ongoing costs (if applicable), and the outcome or process measure(s) against which the recipient will be measured. The OIG has clarified that this writing requirement can be satisfied by a collection of documents.

Similar to the CMS exception, the OIG safe harbor requires annual monitoring. It differs in that the OIG requires the VBE to monitor whether there are material deficiencies in the quality of care or finds that it is unlikely that the arrangement is furthering the coordination of management of care. If the monitoring results in either of these findings, within 60 days, the parties must terminate the arrangement or implement a corrective action plan to cure the deficiencies within 120 days.

Although the OIG ultimately elected not to completely exclude pharmaceutical companies, PBMs, laboratories, and medical device companies from participation in VBEs as originally proposed, under most of the OIG safe harbors there is no protection for remuneration exchanged to and from those entities. The exception is that, under the care coordination safe harbor, the OIG established a pathway for "limited technology participants" (which can include device and medical supply manufacturers and DMEPOS suppliers). If these entities satisfy the requirements applicable to the pathway for limited technology participants, certain remuneration exchanged can be protected, but this is limited to providing "digital health technology" including hardware, software or services used for purposes of coordinating and managing care. Under this exception, the limited technology participant is prohibited from conditioning remuneration on purchases or exclusive use of any item sold by the limited technology participant. The OIG established this limited pathway in recognition that suppliers and manufacturers can provide crucial digital tools that are used in care coordination and should be allowed to participate in this manner.

CMS recognizes in the preamble that in some cases a single corporate entity may operate multiple business lines, including some that would otherwise be excluded. As examples, health systems may be involved in device and technology development, or pharmacies may be under common ownership with a PBM. In these circumstances, the OIG final rules establish a guiding principle that, where the single corporate entity operates multiple business lines, VBE eligibility turns on the entity's predominant or core business.

Patient Engagement and Support Safe Harbor

In the final rule, OIG established a new "patient engagement and support" safe harbor at 42 C.F.R. § 1001.952(hh). In addition to establishing a safe harbor under the AKS, it also serves as an exception from the definition of remuneration under the beneficiary inducement CMP. No corresponding exception has been created under the Stark law, because the focus of the patient engagement safe harbor is on patients, not physicians.

The new safe harbor allows most VBE participants to furnish appropriate, in-kind, preventive, medically necessary tools, items, goods, incentives, services, and supports to patients in a target patient population to promote the patients' engagement with their care and adherence to care protocols and to improve quality, health outcomes, and efficiency. The safe harbor does not apply to certain ineligible entities that are VBE participants, including pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, or wholesalers; pharmacy benefit managers; laboratory companies; compound pharmacies; certain device manufacturers; and DMEPOS suppliers (so long as it is not also a pharmacy, physician, or other provider). That said, the rule permits device manufacturers to furnish patient engagement tools or support that constitute digital health technology.

There are a number of requirements for patient engagement tools and support to be protected. First, the safe harbor is limited to in-kind items, goods, and support. The provision of cash, cash equivalents, and certain types of gift cards are not protected. Second, there must be a direct connection to the coordination or management of care of a target population. Third, the tools or support may not result in medically unnecessary or inappropriate items or services reimbursed by Federal health care programs. Fourth, the tools or support must be recommended by the patient's licensed health care professional. Finally, to be protected, the tools or support must advance at least one of five goals: (1) adherence to a treatment regimen; (2) adherence to a drug regimen; (3) adherence to a follow-up care plan; (4) prevention or management of a disease or condition; or (5) ensuring patient safety.

The final rule does not protect cost-sharing waivers or reductions under this safe harbor. The aggregate retail value of the tools and supports cannot exceed $500 per year (updated annually for inflation). In addition, the availability of patient engagement tools and supports cannot be determined in a manner that considers the type of insurance the patient holds.

OIG finalizes additional requirements for safe harbor protection. The tools or support must be furnished directly to the patient (or a caregiver, family member, or other person acting on behalf of the patient) by the VBE participant (or by an "eligible agent" who cannot be one of the ineligible entities noted above). The VBE participant providing the tools or support must be part of the applicable VBA.

The tools or support cannot be used or exchanged to market other reimbursable items and services or for patient recruitment purposes. The VBE participant is required to make all records and materials documenting compliance with the safe harbor available to the Secretary for a six-year period, upon request. The VBE participant cannot take into account a patient's type of insurance coverage in providing patient engagement tools or support.

In response to comments from stakeholders, the OIG decided not to include several requirements that were previously proposed. The final rule does not require VBE participants to exclude tools or support likely to be diverted, sold, or mis-utilized by a patient or to retrieve the tools or support under certain circumstances. VBE participants are not required to provide written notice to patients receiving tools or support identifying the VBE participant and describing the nature and purpose of the tools or support. The VBE participant is not required to monitor the effectiveness of the tools or support or to confirm that the tools or support are not duplicative of another item that the patient may already have.

New CMS-Sponsored Model Arrangements and Patient Initiatives Safe Harbor

In the final rule, OIG creates a new safe harbor at 42 C.F.C. § 1001.952(ii) designed to simplify the application of the anti-kickback statute and CMP authority for individuals and entities that participate in CMS-sponsored payment models approved by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation under Section 1115A(d)(1) of the Social Security Act and the Medicare Shared Savings Program under Section 1899 of the Act (collectively, the "CMS-sponsored models"). No corresponding exception has been created under the Stark law because CMS believes other existing exceptions are sufficient.

Through this new safe harbor, OIG seeks to provide greater predictability for model participants, as well as uniformity across various models. With the implementation of this new safe harbor, OIG believes the need for separate fraud and abuse waivers from the OIG for new CMS-sponsored models should be "infrequent." The safe harbor under the final rule is largely similar to the proposed rule, although some requirements have been eased and some new requirements have been added.

The safe harbor protects exchanges of value between model participants and patient incentives. Whether the safe harbor is eligible to a particular model depends on whether CMS decides to make it available. The parties to a CMS-sponsored model must reasonably determine that the remuneration advances one or more goal of the model. The OIG provides that remuneration may not induce the furnishing of medically unnecessary care or reduce or limit medically necessary care. Further, the OIG requires that remuneration may not be in exchange for federal health care program referrals or business outside of the particular model.

The final rule stresses the importance of having signed "participation documentation." Model parties must comply with the terms of the particular model in order to obtain protection. The scope of the model and the arrangements or incentives permitted under the model are determined by CMS as defined in the participation documentation. Parties under a CMS-sponsored model must make available to the Secretary upon request all materials sufficient to establish whether the remuneration was exchanged in a manner that meets the condition of the safe harbor.

Modifications and Expansions for EHR and Cybersecurity Donations

OIG and CMS also expanded and modified the existing AKS safe harbor and the Stark law exception for EHR donations. They created a new safe harbor and exception for donations of cybersecurity technology and services, as well.

EHR Donations Clarifications and Expansions

The regulations update existing provisions regarding interoperability, remove sunset provisions, offer options with respect to cost-sharing, and clarify protections for cybersecurity technology and software as part of an EHR donation.

Interoperability (deeming provisions, information blocking and data lock-in)

The existing regulations provide that software is "interoperable," if, on the date it is provided to the physician, it has been certified by a certifying body in accordance with the electronic health record certification criteria identified in the then-applicable version of 45 C.F.R. part 170. The finalized revisions change "it has been certified by a certifying body" to "it is certified by a certifying body" and remove the phrase "electronic health record" preceding certification criteria to align with the current language in 45 C.F.R. part 170 as of June 30, 2020. Under the new rules, the safe harbor and exception merely require that the software is interoperable at the time it is provided to the recipient. The EHR safe harbor and exception will remain available to protect ongoing donations of such EHR software, including updates and patches, if the EHR software is still interoperable, provided that all other requirements of the safe harbor or exception are satisfied. On the other hand, software that loses its certification is no longer interoperable and, therefore, new donations of such EHR software, including updates and patches, would not be protected under the safe harbor or exception.

HHS acknowledged that the Department now has other enforcement authorities designed to address information blocking, such as the 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act), as well as other policy efforts better suited to deter information blocking and penalize individuals and entities that engage in information blocking. Thus, HHS eliminated the information blocking provisions as conditions of the safe harbor and exception.

Cybersecurity

The EHR safe harbor and exception now expressly protect donations of cybersecurity software and services. Prior to this change, "cybersecurity software and services" were not expressly included in the scope of the safe harbor or exception. The agencies declined to expand the EHR safe harbor or exception to apply to additional services or hardware, including hardware that is donated or loaned to a recipient.

Definitions of Interoperability and Electronic Health Records

The OIG and CMS revised the definition of interoperability to align with the statutory definition added by the Cures Act and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). As finalized, interoperable means (1) able to securely exchange data with and use data from other health information technology; and (2) allows for complete access, exchange, and use of all electronically accessible health information for authorized use under applicable state and federal law. Both agencies declined to change the current definition of electronic health record.

Cost-sharing/Contribution Requirements

Both agencies retained the 15 percent cost-sharing contribution for the EHR safe harbor and exception, but revised the requirements related to the timing of payments. As finalized, a physician must pay the required cost contribution amount before receiving an initial donation of EHR items and services or a donation of replacement items and services. With respect to any periodic updates (that are provided after the initial donation and do not constitute a replacement of the EHR), the cost contribution need not be paid in advance. CMS requires physician to pay at "reasonable intervals."

Replacement Technology

Both agencies deleted the prohibition against donating equivalent technology and will now permit donations of replacement items and services. The agencies recognized there may be valid business or clinical reasons for a recipient to replace an entire system rather than update existing technology, even if the existing software meets current certification criteria and does not pose a threat to patient safety.

OIG's Expanded Scope of Protected Donors

The OIG included an expansion of the scope of protected donors to include entities comprised of the types of entities that are currently considered protected donors (e.g., parent companies of hospitals, health systems, and accountable care organizations). In declining to expand the safe harbor protection to all entities, the OIG acknowledged a continuing concern about protecting EHR donations made by laboratories or manufacturers or suppliers of items. Donations from these entities will continue to be ineligible for protection under the EHR safe harbor. CMS did not make a similar change. It is not clear that such a change would have been necessary given the scope of the Stark law.

Sunset Provision

The EHR safe harbor and exception were scheduled to end on December 31, 2021. Both agencies removed the sunset provision and made the safe harbor and exception permanent, noting that the continued availability of these protections provides necessary certainty with respect to the contribution costs related to donations of EHR items and services.

Cybersecurity Exception and Safe Harbor

The OIG and CMS finalized a new, separate cybersecurity technology and related services donation safe harbor and exception. Both agencies found that this protection was necessary to address the growing threat of cyberattacks that infiltrate data systems and corrupt or prevent access to health records and other information essential to the delivery of health care.

The AKS safe harbor and Stark law exception are slightly different, as noted below. However, both cover nonmonetary remuneration (consisting of technology and services) necessary and used predominantly to implement, maintain, or reestablish cybersecurity. The proposed arrangement must then meet the following conditions to qualify for the cybersecurity safe harbor or exception:

1. Under the AKS safe harbor:

- The donor cannot directly take into account the volume or value of referrals or other business generated between the parties when determining a potential recipient's eligibility for donation, or the amount or nature of the technology or services to be donated.

- The donor cannot condition the donation, or the amount or the nature of the donation, on future referrals.

- The arrangement must be documented in writing and signed by the parties, include a general description of the technology and services being provided and the amount of the recipient's contribution, if any.

- The donor must not shift the costs of the technology or services to any federal health care program.

2. Under the Stark law exception:

- The donor cannot condition the donation, the amount or nature of the donation, or the eligibility for donation on the volume or value for referrals or the business generated.

- The arrangement must be documented in writing.

Under both the safe harbor and exception, the donor cannot condition receipt of technology or services, or the amount or nature of the technology or services, on the recipient doing business with the donor.

Newly Defined Terms Under the Cybersecurity Safe Harbor and Exception

HHS has finalized broad definitions of cybersecurity and technology. Both agencies define cybersecurity as the "process of protecting information by preventing, detecting, and responding to cyberattacks." This definition is derived from the National Institute for Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF). The agencies explain that it provides a commonly-understood language for donors and recipients seeking to use the cybersecurity exception to improve their cybersecurity posture.

The finalized definition of technology is "any software or other types of information technology," which may include hardware, as long as all of the hardware is necessary and used predominantly to implement, maintain, or reestablish cybersecurity. The agencies explained that the cybersecurity safe harbor and exception could be applicable to hardware such as encrypted servers, encrypted drives, and network appliances under this framework. Further, as long as the requirements of the safe harbor or exception are satisfied, including the requirement that the donated hardware is necessary and used predominantly to implement, maintain, or reestablish cybersecurity, the following single-function or standalone cybersecurity hardware could be permitted:

- Computer privacy screens

- Two-factor authentication dongles

- Security tokens

- Facial recognition cameras for secure access

- Biometric authentication

- Secure identification card and device readers

- Intrusion detection systems

- Data backup systems

- Data recovery systems

The agencies posit that the broad definition of technology, coupled with the requirement that any donated hardware is necessary and used predominantly to implement, maintain, or reestablish cybersecurity, provides flexibility while safeguarding against program or patient abuse.

Other Notable Requirements:

- No restriction on the types of entities that may make cybersecurity donations under the safe harbor or exception.

- No recipient contribution requirement.

- Help desk services or staffing a recipient's practice with a full-time cybersecurity officer could meet the requirement if used predominately for implementing, maintaining, or reestablishing cybersecurity and all other conditions were satisfied under the safe harbor or exception.

- No monetary value limit on the total amount of donations that a donor can make to a recipient.

- All donations must be nonmonetary (e.g., no protection for payments of any ransom to or behalf of a recipient in response to a cyberattack).

- No "deeming" provision that would allow parties to otherwise demonstrate compliance with the cybersecurity safe harbor or exception.

Clarifying Guidance for Stark Compensation Analyses

CMS finalized new rules intended to simplify essential terms for analyzing compensation arrangements under the Stark law. Among other things, the new rules provide guidance regarding the meaning of commercially reasonable, volume or value and other business generated standards and fair market value as they relate to compensation arrangements. Definitions were revised, exceptions clarified, and a new exception for limited remuneration to a physician was created. The result of these revisions and additions is greater insight into CMS' process in analyzing financial relationships between physicians and entities.

Commercial Reasonableness

Until now, there has been no codified definition of the term commercially reasonable in the physician self-referral regulations. Given how pivotal this term is to numerous analyses under the Stark law, CMS finalized its proposed definition of commercially reasonable with some modifications (§ 411.351). Under the final rule, commercially reasonable means the arrangement furthers a legitimate business purpose of the parties to the arrangement and is sensible, considering the size, type, scope and specialty of the parties. In clarifying the definition of commercial reasonableness, CMS stated that the key question to consider when determining if an arrangement is commercially reasonable is whether the arrangement makes sense as a means to accomplish the goals of the parties. CMS noted, "the determination of commercial reasonableness is not one of valuation." In addition, CMS explained that the determination as to whether an arrangement is commercially reasonable does not depend on whether the arrangement is profitable and that compensation arrangements that are not profitable for either of the parties may nonetheless be commercially reasonable. CMS specifically codified this view.

Volume or Value of Referrals and Other Business Generated Standards

CMS' final rules on the volume or value standard and other business generated standard expressly supersede CMS' previous rules and guidance. While not adding a definition of volume or value, CMS codified the meaning of the term volume or value of referral and other business generated within the special rules on compensation. CMS' new rules address both compensation to a physician and compensation from a physician. The rules are further subdivided to address compensation that varies based on the volume or value of referrals and compensation that varies based on other business generated.

Under the new rules, at §411.354(d)(5) and (6), compensation is considered to take into account the volume or value of referrals or take into account the volume or value of other business generated "only when the mathematical formula used to calculate the amount of the compensation includes referrals or other business generated as a variable, and the amount of the compensation correlates with the number or value of the physician's referrals to or the physician's generation of other business for the entity." In response to a number of stakeholders who raised concerns about the implications of a case like United States ex rel. Drakeford v. Tuomey Healthcare System, Inc., 792 F.3d 364 (4th Cir. 2015), CMS reaffirmed that a productivity bonus for employed physicians would not be viewed as taking into account the volume or value of the physician's referrals solely because designated health services are billed each time the employed physician personally performs a service.

To further its objective of creating a bright line rule regarding what CMS considers taking into account the volume or value of referrals or other business generated, it chose not to identify circumstances not to have been determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of referrals or takes into account other business generated between the parties. Rather, CMS identifies the universe of arrangements that will be considered to take into account the volume or value of referrals or other business generated. CMS also clarified that a determination that a compensation takes into account the volume or value of referrals or the volume or value of other business generated under the new rules will be final, and that the old unit-based special rules deeming provisions will not apply. The provisions in (d)(2) and (d)(3) have not been removed, however, because they may need to be referred to for historical purposes. The final rules would be applied whenever the regulations refer to compensation "taking into account," "related to," or "based on" the volume or value of referrals or other business generated. The final rules also apply to the definition of remuneration at §411.351, the exception for academic medical centers, various exceptions for compensation arrangements at §411.357, including the new final rule exception for limited remuneration to a physician, and the group practice regulations. The rules do not apply to the exceptions for medical staff incidental benefits, professional courtesy, community-wide health information systems, electronic prescribing items and services, electronic health records items and services, and cybersecurity technology and related services, because those exceptions do not lend themselves to mathematical formulas.

We note that CMS did not finalize its proposal for additional special rules to outline the circumstances where fixed-rate compensation would be determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of referrals or other business generated by a physician for the entity paying the compensation.

In line with the other changes made to the volume or value standard and the other business generated standard, CMS removed the modifiers "directly or indirectly," commonly used in the descriptor for compensation arrangements, from the regulations in instances where the modifiers appear in connection with the standards. CMS believes it is implicit that a compensation that is not determined in any manner that takes into account the volume or value of referrals would not do so directly or indirectly. CMS notes that the changes to the modifiers would not affect instances where the statute or regulations specifically allow the parties to determine the compensation in a manner that indirectly takes into account the volume or value of referrals, such as the exception for electronic health records items and services at §411.357(w)(6).

With respect to the group practice provision at §411.352(g) and (i), the rules apply to ensure that a physician member of a group practice cannot receive compensation that directly or indirectly takes into account the volume or value of referrals for designated health services unless it is otherwise permitted by the special rules for profit shares and productivity bonuses. Additional changes to the group practice arrangements are discussed in the group practice section below.

Fair Market Value and General Market Value

CMS also finalized a new definition of fair market value (FMV) to mean "the value in an arm's-length transaction, consistent with the general market value of the subject transaction." In addition, the agency specifically defined the term FMV for transactions related to equipment and office space lease. With respect to the rental of equipment, FMV is the value of the rental equipment in an arm's-length transaction for general commercial purposes, regardless of its intended use and consistent with the general market value of the transaction. Similarly, for an office space rental it is the value of the rental property in an arm's length transaction, regardless of its intended use and without any adjustment to reflect the additional value the prospective lessee or lessor would attribute to the convenience or proximity to the lessor, where the lessor is a potential referral source.

CMS took a similar approach in its definition of general market value. The agency finalized new definitions for general market value, as it relates to an asset acquisition, compensation for services and rental of equipment or office space. Under the new rules, general market value with respect to the purchase of an asset means the price that an asset would generate on the date of the acquisition as a result of a bona fide bargain between well-informed parties who are not otherwise in a position to generate business for each other. With respect to compensation for services, general market value means compensation that would be paid at the time the parties enter into the service arrangement as a result of a bona fide bargain between well-informed parties that are not otherwise in a position to generate business for each other. General market value for the rental of equipment or the rental of office space, is defined as the price that rental property would generate at the time of the rental arrangement as a result of a bona fide bargain between well-informed parties that are not otherwise in a position to generate business for each other.

CMS also finalized its proposal to remove the rental payment language under the definition of fair market value at §411.351. Specifically, the language that states that "a rental payment does not take into account intended use if it takes into account costs incurred by the lessor in developing or upgrading the property or maintaining the property or its improvements." CMS states the language was removed because it created confusion, but that removal should not to be interpreted as disagreement with the statement.

Notably, CMS did not finalize its proposal to equate general market value with "market value." It states, "[o]ur use of the term "market value" in our preamble discussion, although not carried into the proposed definition of "general market value," may have been inaccurate. Therefore, we are retracting our statements equating "general market value," as that term appears in the statute and our regulations, with "market value," the term we identified as uniformly used in the valuation industry." The finalized rules related to fair market value can be found at §411.351.

Modifications to the Group Practice Definition

As stated above in our discussions related to the volume or value and other business generated standard, the terms "takes into account," "based on," and "related to" under the group practice provisions should be interpreted as incorporating the volume or value standards related to a physician's referrals. This means that compensation, profit shares and productivity bonuses to a physician member of a group practice may not be determined in any manner that directly takes into account the volume or value of the physician's referrals.

In connection with the new value-based exceptions, CMS finalized a deeming provision related to the distribution of profits from designated health services that are directly attributable to a physician's participation in a value-based enterprise. This distribution would be deemed not to directly take into account the volume or value of the physician's referrals and would enable physicians in a group practice who are participating in value-based arrangements to be rewarded for their participation in such models. This accommodates groups where not all of the physicians in the group participate in value-based arrangements.

In addition, CMS reiterated its view that the distribution of overall profits of all DHS for the whole group or any component of a group of five or more physicians must be aggregated before distribution. CMS rejected comments that designated health services could be distributed to group practices based on a service-by-service basis, such as distributions of profits from clinical laboratory services to a subset of physicians and distributions of profits from diagnostic imaging to a different subset of physicians. Recognizing that group practices may need to modify their compensation arrangements, CMS delayed the effective date of this change until January 1, 2022. Changes to the group practice provisions can be found at §411.352.

Patient Choice and Directed Referrals (§411.354(d)(4))

The special rules for directed referrals permit directed referrals under certain arrangements. Under this provision, an entity can direct a physician who is an employee, independent contractor, or party to a managed care contract to refer to a specific provider, practitioner, or supplier. Due to the importance of maintaining patient choice, certain conditions must be satisfied including the arrangement. Compensation to a physician is not considered to take into account the volume or value of his or her referrals, as long as the directed referral requirement does not apply if a patient expresses a preference for a different provider, practitioner, or supplier; the patient's insurer determines the provider, practitioner, or supplier; or the referral is not in the patient's best medical interests in the physician's judgment. If a referral requirement is part of a compensation arrangement, the requirement must be set out in writing and signed by the parties.

Additionally, if there are directed referrals, compensation to the physician must be set in advance for the term of the arrangement and remain consistent with fair market value, and the elements of an applicable exception must be satisfied. CMS emphasized how important the patient choice protections are when a referral requirement is in place and added an affirmative requirement to many exceptions that the arrangement meet the conditions of the revised special rule at §411.354(d)(4). The exceptions impacted include the exceptions at §411.355(e) for academic medical centers, §411.357(c) for bona fide employment relationships, §411.357(d)(1) for personal service arrangements, §411.357(d)(2) for physician incentive plans, §411.357(h) for group practice arrangements with a hospital, §411.357(l) for fair market value compensation, and §411.357(p) for indirect compensation arrangements. The requirement also extends to the new exception finalized in this rulemaking for limited remuneration to a physician at §411.357(z). As discussed previously, the new value-based arrangements exceptions at §411.357(aa) have specific requirements included that relate to remuneration conditioned on directed referrals.

In the final rule, CMS expressed concern related to program or patient abuse when an arrangement provides that a physician will not receive future compensation if he or she fails to refer as required. The same concern arises if the physician's compensation is tied to the physicians' referral to a particular provider, practitioner, or supplier. To address this concern CMS added a condition at §411.354(d)(4)(vi) that states neither the existence of the compensation arrangement, nor the amount of the compensation is contingent on the number or value of the physician's referrals to the particular provider, practitioner, or supplier. This condition must be met regardless of whether the physician's compensation takes into account the volume or value of his or her referrals to the entity with which the physician has the compensation arrangement. A physician's compensation arrangement cannot be based, that is increased, decreased, or terminated, based on either the number of referrals made, nor the value of those referrals. CMS does permit an established percentage or ratio of referrals to be made a certain entity, practitioner or supplier.

Special Rules on Compensation

CMS has provided past guidance on noncompliance related to a missing signature required for an applicable exception. In recognition of arrangements that may be found noncompliant due to a missing or late signature alone, the regulations have been expanded to provide additional flexibility that CMS believes does not pose a risk or program or patient abuse. For instance, the special rule for temporary noncompliance at §411.353(g) permitted parties to obtain signatures within 90 consecutive calendar days. In the 2019 PFS final rule, CMS removed the provision that limited the use of this special to once every three years with respect to the same physician.

In response to comments received, CMS finalized certain modifications to the special rule on compensation arrangements at §411.354(e). Due to the low risk related to arrangements that comply with an applicable exception, but for a missing signature or lack of writing, CMS has included a provision that any requirement for a compensation arrangement to be in writing and signed by the parties, will be satisfied if the parties obtain the writing(s) or signature(s) within 90 consecutive calendars days immediately following the date on which the arrangement became noncompliant. While parties must pay attention to when the clock begins for the 90 consecutive calendar days, this flexibility, along with the ability to determine that the compensation under an arrangement is set in advance via a collection of documents, will assist parties in satisfying the elements of an exception more easily at the outset of the arrangement. While it is still a recommended best practice to have the arrangement in place and in compliance with an applicable exception prior to services being rendered or payment being made under an arrangement, parties now have the 90 days to ensure this occurs. Coupled with the new exception at §411.357(z) for limited remuneration to a physician, parties have new options when considering the path to compliance with an exception.

While CMS permits 90 days to obtain the required writing and signature at the outset of the arrangement, the same flexibility does not apply to modifications of the compensation terms. It is critical to note that all modifications to compensation must fully satisfy the elements of an exception before the modification takes effect. These modifications can occur at any time, including during the first year of the arrangement, and without limit as to the frequency. However, CMS warns that the more frequent the changes to the compensation arrangements, the more concerning it may appear that these modifications reflect the volume and value of referrals from the physician or other business generated between the parties.

Period of Disallowance

CMS finalized its proposal to delete the rules on the period of disallowance in their entirety. The existing rules were meant to create the outermost limit of the time period of non-compliance and to provide assurance that noncompliance had ended. Instead, the rules have resulted in confusion when identifying the time period a physician is not permitted to make referrals. Rather than a set of prescriptive rules to determine the period of noncompliance, CMS discusses the consideration of the unique facts and circumstances of the financial relationship and how the parties operate under the arrangement in order to determine when the financial relationship has ended. While recovery of excess compensation can end the period of noncompliance, CMS is clarifying that this is not the only way to do so.

The identification and correction of noncompliance is important to CMS and can demonstrate an effective compliance program. In the proposed rule, CMS discussed its view that parties that identify administrative or operational errors or payment discrepancies during the course of an arrangement are able to cure the potential noncompliance. If this is accomplished during the term of the arrangement CMS classifies this as addressing a current problem and is not "turning back the clock." In response to commenters, as well as experience with self-disclosure submissions, CMS has extended the opportunity for the identification and correction of potential noncompliance. The final rule includes a special rule for reconciling compensation at §411.353(h) if the parties to the compensation arrangement reconcile all payment discrepancies in the arrangement within 90 consecutive calendar days of expiration or termination of the compensation arrangement, so long as the arrangement satisfied all other elements of an applicable exception during the duration of the arrangement.

CMS also offered guidance regarding potential noncompliance when the actual arrangement in practice between the parties does not match up with the terms included in the written documentation. In these instances, parties should look to the amount of compensation the physician actually received in determining whether the actual arrangement was documented and, if needed, corrected.

The additional flexibility in addressing potential noncompliance during the term of an arrangement, as well as 90 days post termination of an arrangement will likely decrease the incidence of noncompliance reported under the physician self-referral disclosure protocol for those parties with robust and effective compliance programs.

Indirect Compensation

CMS revised the definition of indirect compensation in a different manner than considered in the proposed rule. If an indirect compensation arrangement does not meet the definition under the Stark law, an exception is not needed as the referral prohibition does not apply.