New regulations issued by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) of the People’s Republic of China (the PRC) became effective on 1 June 2014. These regulations (the Regulations) will have a significant effect on the ability of lenders to take, and borrowers to provide, cross-border guarantees and security for PRC-related financings.

This memorandum looks at the Regulations and examines some of the changes in financing practice that we may expect to see in PRC-related financings.

Before the Regulations

The general position before the Regulations came into effect on 1 June 2014 was that, with some exceptions (most notably those exceptions relating to PRC banks and other financial institutions operating within their SAFE annual quotas):

-

PRC entities could not provide guarantees or security for offshore PRC financings without obtaining SAFE approval on a case-by-case basis and registering the guarantee or security in question with SAFE; and

-

Only certain limited types of PRC entities were permitted to borrow from onshore PRC financial institutions on the basis of offshore guarantees and security provided by an offshore entity, and there were stricter limits on the ability of the onshore borrower to reimburse the offshore guarantee or security provider in the event that the latter was called upon to pay out under its guarantee or security commitment.

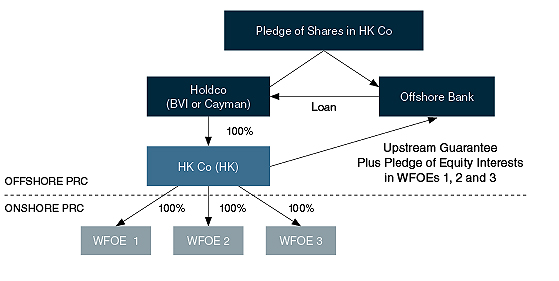

In practice, aside from certain limited types of guarantees and security (e.g., guarantees given by PRC State Owned Enterprises in relation to bond offerings by subsidiaries sold outside the PRC), SAFE generally would not give its approval for such guarantees or security proposed by non-bank PRC entities. Consequently, the practical effect was that it was impossible to incorporate guarantees or security of this nature into many PRC-related financings. This led to the classic offshore/onshore PRC financing structure illustrated below:

As can be seen in this structure, although Offshore Bank has a Pledge over the Equity Interests in WFOEs (wholly foreign-owned enterprises) 1, 2 and 3, it has no guarantee from, or security over any of the assets of, WFOEs 1, 2 and 3. Consequently, in this structure Offshore Bank is structurally subordinated to all the creditors, secured and unsecured, of WFOEs 1, 2 and 3.

In many PRC businesses, all the revenue-producing and other physical assets (e.g., land-use rights, factories, machinery, inventory, intellectual property, etc.) are located in the WFOEs (i.e., onshore) with the offshore Holdco, and the offshore intermediate holding companies, simply serving as share-holding companies with no “real assets”. In addition, in the classic offshore/onshore structure identified above, the WFOEs likely will have sourced much of their working capital and other operational financing requirements from local PRC banks on both a secured and unsecured basis.

The logical result of this structure is that when one of these PRC businesses gets into financial difficulties, the Offshore Bank lender is in a very disadvantageous position:

-

It has no recourse to any of the assets of the WFOEs;

-

It is structurally subordinated to all creditors of the WFOEs (including PRC lenders and the employees of the WFOEs);

-

It has no standing or seat at the table in any workout or insolvency proceedings relating to the WFOEs in the PRC;

-

It is at the mercy of deals struck in the PRC between lenders to the WFOEs, the WFOEs’ employees, the onshore individuals who own the Group (the Founder(s)) and other powerful interested parties, such as the local government in the PRC region where the business is located, who will be loath to see a conclusion reached that endangers local interests, e.g., local employment, payment of local taxes, etc.

As has been seen in examples such as Asia Aluminum and other less publicized cases, when an offshore/onshore structure of the type identified above gets into financial difficulties, the Offshore Bank (and other lenders to the offshore group, such as offshore bondholders) often are in very weak and unsatisfactory positions.

The Regulations

The Regulations have a significant effect on the previous position.

The Regulations apply to what are now termed “Cross-Border Guarantees”. Essentially, a Cross-Border Guarantee is a guarantee or security provided under a written, legally binding commitment that may give rise to cross-border payments and receipts, cross-border transfers of assets or other effects resulting in the transfer of funds into and out of the PRC.

The Regulations divide Cross-Border Guarantees into the following main types:

-

Nei Bao Wai Dai: Onshore security for offshore credit — this refers to guarantees or security provided by an onshore PRC entity to an offshore creditor entity in respect of an offshore financing made available to an offshore debtor entity;

-

Wai Bao Nei Dai: Offshore security for onshore credit — this refers to guarantees or security provided by an offshore entity to an onshore creditor entity (which must be a financial institution) in respect of an onshore financing made available to an onshore debtor entity (which is not a financial institution); and

-

Cross-Border Guarantees of other types.

The Regulations are clear in some areas and less clear in other areas, and there will no doubt be a settling-in period during which the market and the PRC law firms come to a consensus on what can be done under the Regulations without SAFE approval, but the following conclusions at least seem to be clear:

-

The Regulations significantly improve the position of offshore lenders looking to take guarantees or security from onshore entities to support financing made available to offshore borrowers;

-

In many cases no approval is now required from SAFE, whereas before the Regulations came into force SAFE approval was required and in practice in most cases was not obtainable;

-

Registration of Cross-Border Guarantees with SAFE is still required in many cases, but unlike the situation before the Regulations came into effect, failure to register will not necessarily adversely affect the validity or enforceability of the guarantee or security in question, though the provider of the guarantee or security may be subject to SAFE administrative penalties for failure to register;

-

In certain cases, the Regulations continue (and expand upon) the previous rules, which prohibited the ability to repatriate the proceeds of the financing in question directly or indirectly into the PRC. As a result, the Regulations do not provide a solution to all financing needs. Where the funds being raised are destined to be used in the PRC (e.g., the many high yield bond and other financings raised by PRC property developers in which the proceeds are intended for use in the PRC), the Regulations are of limited use. The Regulations are of greater potential use where the funds being raised offshore are intended for use offshore — for example, to finance a take-private of a non-PRC company; and

-

It will be easier to use the Regulations where the financing in question is in the form of a loan as opposed to an issue of bonds.

Consequences and Looking Ahead

The introduction of the Regulations will go some way to improving the position of offshore lenders providing finance to offshore holding companies of PRC businesses. It should now be possible in the above example for Offshore Bank to receive the benefit of upstream guarantees and security from WFOEs 1, 2 and 3. This at least will give Offshore Bank a seat at the table in any subsequent restructuring of the business of the WFOEs and should hopefully lead to potentially better outcomes for financiers in the position of Offshore Bank in the event of financial difficulties affecting the PRC business.

It will be interesting to see how the market reacts to the introduction of the Regulations. Questions and issues likely to arise include:

-

When an onshore entity guarantees the offshore debt of an offshore entity (Nei Bao Wai Dai), how and where will the guarantee be documented and what will its governing law be? As any such guarantee will need to be enforced through the PRC courts, there is an argument for making it subject to PRC law and having it executed in Chinese (or in both English and Chinese) and in a form that will be familiar to a PRC court, to assist the process of enforcement in the PRC courts. The offshore credit agreement (which will be in English) will be a substantial document and will include guarantees from the offshore entities. It would be possible to incorporate the guarantees from the WFOEs into this document, but on enforcement it then would be necessary to present a Chinese translation of the whole (lengthy) offshore credit agreement to the PRC court, which might cause enforcement problems. A possible solution would be to have the WFOEs execute the offshore credit agreement as guarantors but, in addition, have the WFOEs execute a separate standalone guarantee in Chinese (or in both English and Chinese) that would be used to present to the PRC court if court enforcement in the PRC were ever necessary. This separate guarantee could be subject to PRC law; alternatively, the separate guarantee could be subject to Hong Kong law and provide for arbitration in Hong Kong, with enforcement of the guarantee being achieved by means of the enforcement in the PRC courts of a Hong Kong arbitral award pursuant to the “Arrangement Concerning Mutual Enforcement of Arbitral Awards Between the Mainland and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region”, following an arbitration in Hong Kong to obtain an arbitral award in respect of the guarantee.

-

Under the classic offshore/onshore structure illustrated above, WFOEs historically have not been made party to the offshore credit agreement and have thus not been directly bound by the various covenants and undertakings given by Holdco in respect of the entire group of companies (offshore and onshore) in the offshore credit agreement — for example, the negative pledge and the restrictions on borrowings, guarantees, disposals, acquisitions, etc. We may now see practice on this change, and offshore lenders may begin to require the WFOEs to become party to the offshore credit agreement so as to directly bind themselves to comply with the various covenants regulating the operation of the group’s business, thus further strengthening the offshore lender’s hand in any subsequent restructuring negotiations.

-

Download PDF

* * *