AliceStorm at the USPTO

While AliceStorm's effect is most visible in the courts, because of their public nature, the real impact is largely unseen: it is the widespread rejection of patent applications by the USPTO. The number of patent applications that have been rejected specifically based on Alice is vastly larger than the number of invalidated patents: well over 36,000 applications have been rejected based on Alice, and over 5,000 such applications having been abandoned.1

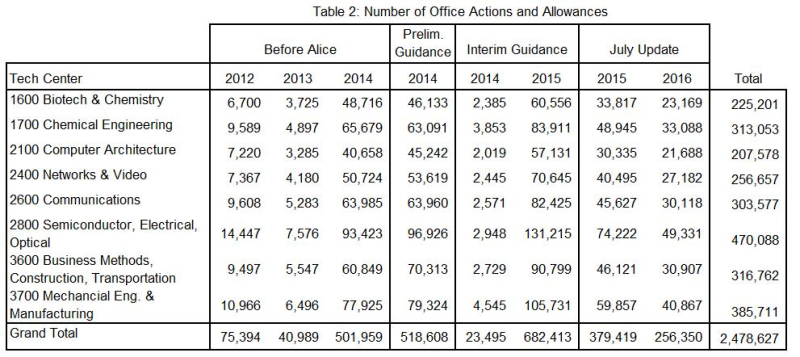

With the assistance of Patent Advisor, I have collected a large database of USPTO prosecution events (office actions and notices of allowances) issued over the past several years. Table 2 is summary of the number of prosecution events analyzed, with respect to USPTO technology centers, and various time periods:2

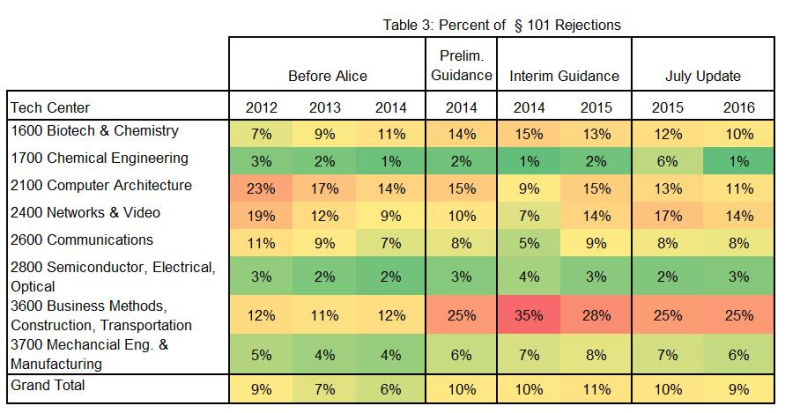

Each office action is coded as to its type (final, non-final) and the rejections therein (§ 101, 102, 103, 112) and whether it cites Alice, Mayo, or Myriad. Table 3 show the percentage of § 101 rejections (as a total of all prosecution events) per period and technology center.3 Low rejection rates are shaded green, high rates red:

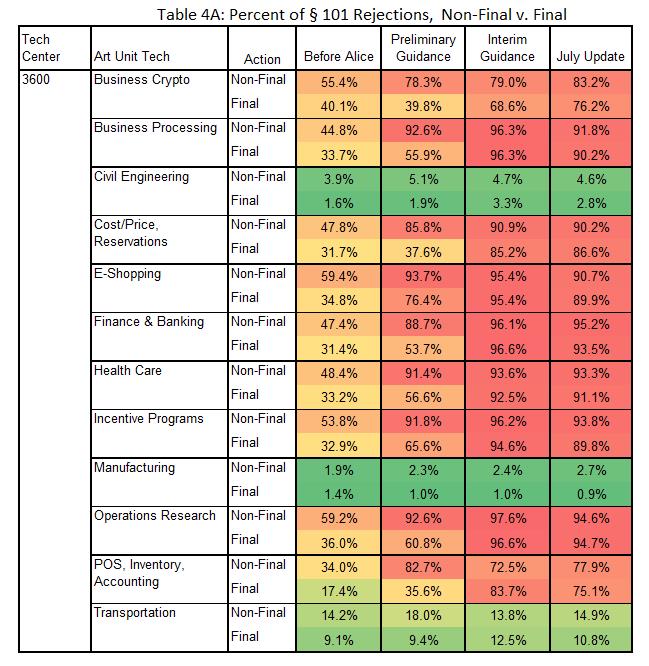

As I explained last year, Tech Center 3600 covers not just business methods, but a variety of traditional technologies, such as transportation, construction, agriculture, aviation and so forth. If we drill down into Tech Center 3600 to the level of the specific types of art unit technologies we have significantly higher § 101 rejection rates:

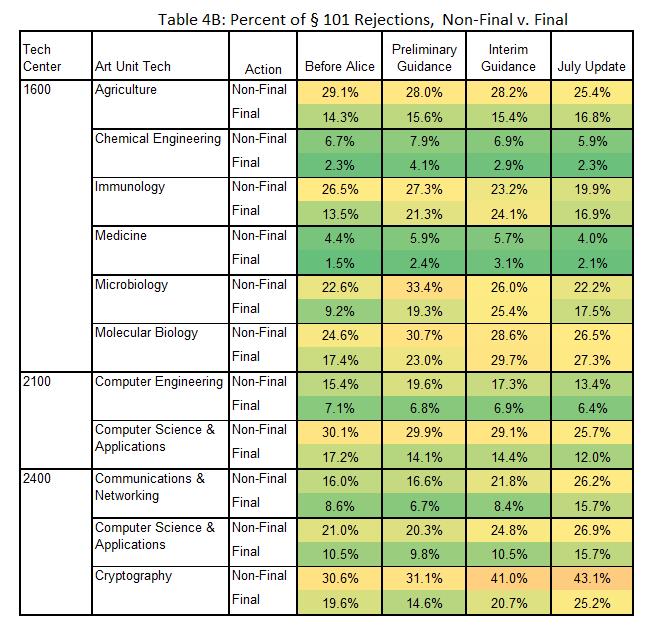

Table 4A provides an additional level of granularity, showing the § 101 rejection rates for both non-final and final rejections. We see here that E-commerce related work groups4 have maintained consistently high rates of § 101 rejections. In addition, comparing the non-final and final rejection rates we see that there is very little difference between the two, generally around a 2 percentage point drop (and sometimes an increase!). This means that these examiners rarely withdraw a § 101 rejection, regardless of the applicant's arguments or amendments. Compare this behavior to examiners in Tech Centers 1600 (Biology), 2100 (Computer Architecture) and 2400 (Computer Networks):

First, the overall § 101 rejection rates are dramatically lower. The relatively low rejection rates in computer science related applications is noteworthy because inventions in computer science inherently rely on forming abstract representations of the problem domain and solution, gathering data, performing some steps that can almost always be reduced to mathematics, and then outputting a result—all using a general purpose computer. These are precisely the steps we're frequently told that are nothing more than applying an abstract idea on a generic computer, with trivial pre- and post-solution activity. Even applications in cryptography, with their extremely heavy emphasis on mathematical algorithms, do not suffer the levels of abstract idea rejections seen in E-commerce. Similarly, applications in biotechnology--which are suspect anytime there is any claimed correlation between biological markers and an identifiable biological event or condition—are far less frequently rejected for ineligibility.

First, the overall § 101 rejection rates are dramatically lower. The relatively low rejection rates in computer science related applications is noteworthy because inventions in computer science inherently rely on forming abstract representations of the problem domain and solution, gathering data, performing some steps that can almost always be reduced to mathematics, and then outputting a result—all using a general purpose computer. These are precisely the steps we're frequently told that are nothing more than applying an abstract idea on a generic computer, with trivial pre- and post-solution activity. Even applications in cryptography, with their extremely heavy emphasis on mathematical algorithms, do not suffer the levels of abstract idea rejections seen in E-commerce. Similarly, applications in biotechnology--which are suspect anytime there is any claimed correlation between biological markers and an identifiable biological event or condition—are far less frequently rejected for ineligibility.

Further, compare the drop in § 101 rejection rates between non-final to final rejections. Here we see significant reductions. For example, in TC 2100, Computer Science & Applications in both the Interim Guidance and July Update period, the § 101 final rejection rate is less than half the non-final rate. This means that these examiners are withdrawing their rejections—presumably equally well founded as their peers in E-commerce—in response to arguments and amendments by the applicants.

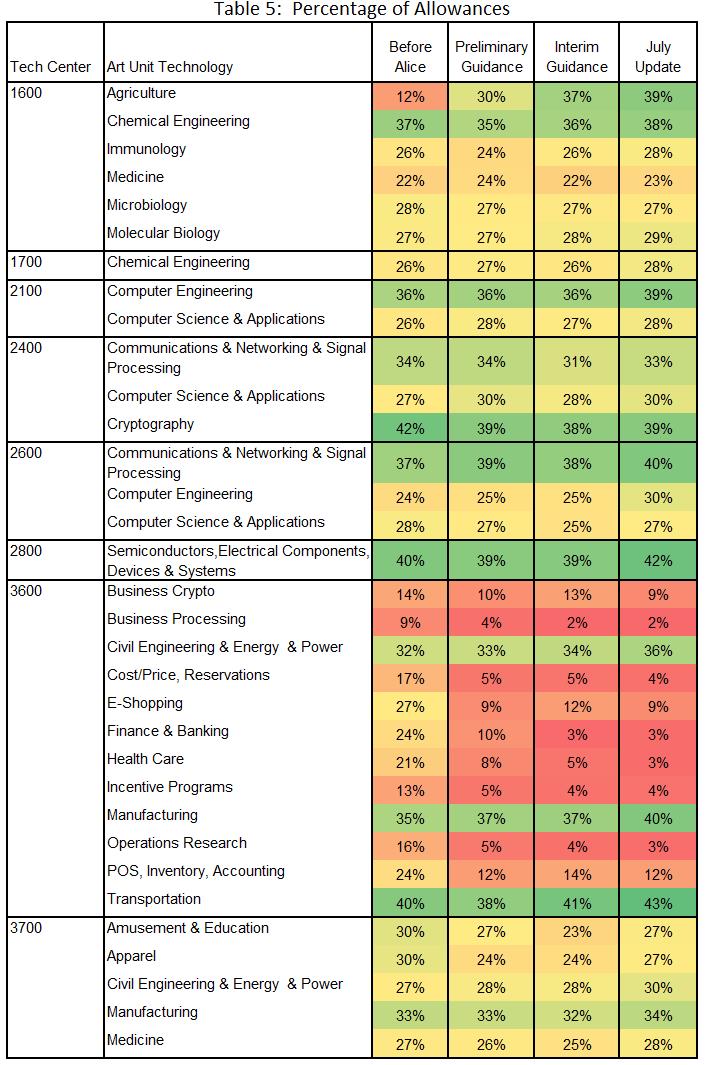

We see the same differential behavior in the rates of notices of allowances across the technology centers:

Here, the E-commerce work groups have very low rates of allowances5 relative to other work groups. More important, we can see that over time, the allowance rates in every other technology center have slightly increased, whereas in the E-commerce work groups they have either remained flat or declined by one or two points.

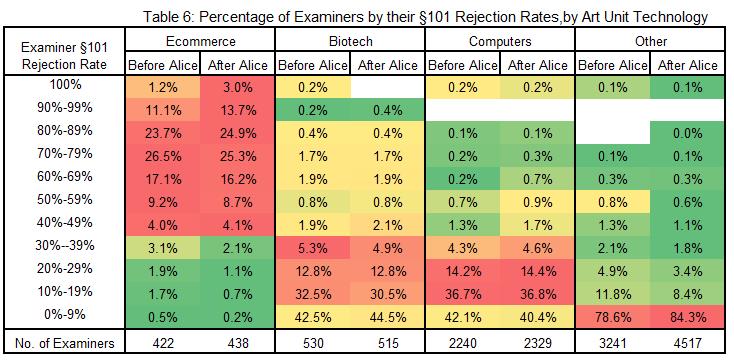

Another way of understanding the behavior of examiners is to consider their individual rates of § 101 rejections: the percentage of office actions by an examiner that contain a § 101 rejection. Table 6 illustrates:

The left column ("Examiner § 101 Rejection Rate") are percentage bins for the percentage of office actions by an examiner that include a § 101 rejection. The top row, for example, are those examiners who have issued a § 101 rejection in every office action in the indicated period (Before Alice or After Alice). Some observations:

-

Thirteen E-commerce examiners out of 438 have a 100% Section 101 rejection rate—compared to just seven out of 7,361 examiners in the rest of the USPTO. This stands in contrast to last year’s survey, which reported that 58 E-commerce examiners had 100% Section 101 rejection rates.

-

Last year, E-commerce examiners with § 101 rejection rates of 50% or more accounted for 88.8% of their examination corps. This year that has edged up to 91.7%. By contrast, in biotechnology only 5.2% of examiners have a 50% or more § 101 rejection rate; 2.2% in Computers, and a minuscule 1.1% in the rest of the examination corps.

-

Last year, there were (only) 20 E-commerce examiners in the 90% bin (row 2) and 49 in the 80% bin (row 3). This year: 60 examiners in the 90% bin (a 3x increase) and 109 in the 80% bin (a >2x increase).

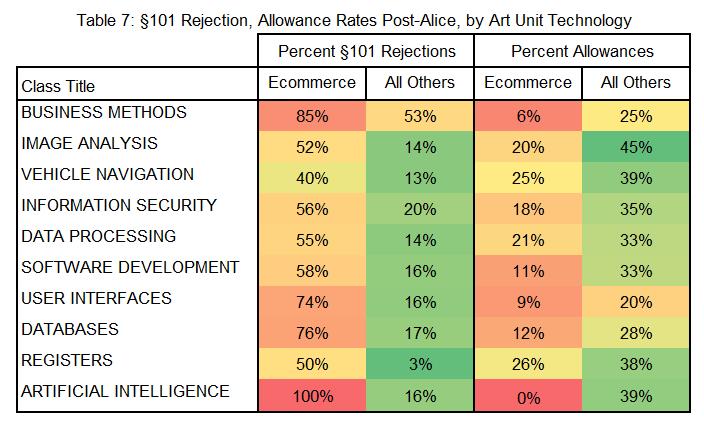

One of the potential rebuttals to the foregoing is that one would expect E-commerce examiners to have higher § 101 rejection rates because the applications they review tend to be more directed towards economic behavior, and thus abstract ideas. That hypothesis is undermined by the following:

Table 7 shows the respective § 101 rejection rates and allowance rates of E-commerce examiners as compared to examiners in all other art units with respect to the top ten technology classes of the examined applications (n=98,951) reviewed in the E-commerce art units. This allows an "apples-to-apples" comparison of examination behavior. What we find is that in every class, E-commerce examiners reject similarly classified technology under § 101 at significantly higher rates than their peers. Significantly, when examiners outside of the E-commerce work group examine business method patents, they issue § 101 rejections only 53% of the time. We also see that E-commerce examiners have a consistently lower allowance rate than their peers.

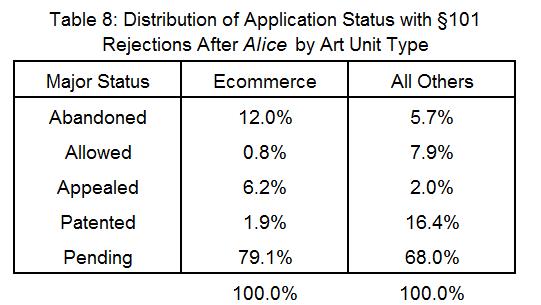

Finally, Table 8 shows the 98,951 applications from Table 7 in terms of their application status:6

Of applications in the E-commerce area that received a § 101 rejection, 12% of those abandoned, compared to similarly rejected applications in other art units. Similarly, a much higher percentage of E-commerce applications with § 101 rejections cases are appealed.

Conclusion

Alice has had dramatic impacts on both software and business method patents. Not unexpectedly, in the federal courts business method patents have fared poorly, being invalidated under § 101 about 77% of the time. The courts have been almost equally hostile to software patents, invalidating 64% of software patents under Alice—even though Alice did not set forth any general rule that software patents are suspect, let alone presumed ineligible.

More surprising, however, is the impact on pending patent applications before the USPTO—an impact that I believe is far more consequential in the long run. If a patent is invalidated, then the only loser is the patentee: the public still gains all the benefit of the bargain because the invention has been disclosed to the public, and in some cases, the technology has been brought to market, thus further benefiting society through whatever gains the invention offers—improved quality, reduced costs, new functionality, or the like. In short, the public got what it "paid" for, and then suddenly received a potentially significant rebate—the early termination, sometimes by many years, of the patentee's rights. This is of course true when a patent is invalidated on any grounds, not just § 101; the difference here is that the rules of eligibility have radically changed midstream, whereas the rules of novelty, non-obviousness, claim construction have not.

In contrast, for patent applications that are never issued—they are abandoned following § 101 rejections, the public many receive no benefit whatsoever if the application was never published—which is not unusual for many small startups. And even if the application is published before being abandoned, the absence of patent protection may result in the company deciding to not bring the technology to market or worse: the company may simply go out of business. These results seem much worse outcomes than issued patents that will never, in fact, monopolize some overly grand statement of an "abstract idea." And if a company, perceiving the odds against both getting through the USPTO and surviving in court, decides to forego developing a pioneering technology—say, tackling the hardest problems of artificial intelligence or biotechnology, or both—then the loss to society simply cannot be measured.

It is true that Alice has been successfully used to combat patent troll litigation based on poor quality patents—and that society benefits when these patents are invalidated. But the price of such benefits cannot be measured because we cannot know at what costs these outcomes came: we will never know what inventions did not get funded and developed because of Alice. That is why it is necessary for the courts and the USPTO to tread carefully.

________________________________

Footnotes:

1 Actually, it's worse than that because statistics presented here are based on published applications, which have historically accounted for 60% of all patent applications. It is reasonable to assume that unpublished applications get the same treatment with respect to § 101 as published ones. The upshot: the actual number of applications rejected due to Alice is likely closer 60,000, and the number abandoned is likely closer to 8,400.

2 The data has been collected through March 31, 2016. "Before Alice" is the period before June 19,2014; "Preliminary Guidance" is the period from June 19, 2014 to December 13, 2014; "Interim Guidance" is the period from December 14, 2014 to July 30, 2015; "July Update" is the period from July 31, 2016 to May 4, 2016.

3 In the following tables, the percentages reflect the number of office actions of a given type divided by the total number of prosecution events (office actions and notices of allowance) issued in the indicated period. Thus, these are percentages of event occurrences. The figures are highly correlated with, but different than the percentages of applications rejected or allowed during the periods, since a given application may be rejected multiple times. In my view, this number is a more accurate reflection of examiner behavior than simply tallying rejected or allowed applications themselves.

4 Work Groups 3620, 3680 and 3690. See http://goo.gl/hOcZOY for details.

5 As above, allowance rates here are the percentage of prosecution events that are notice of allowance. Not all cases that are allowed end up issuing as patents. Thus, these rates should not be interpreted as the percentage of applications in these work groups that issue as patents. Those numbers are generally a bit lower.

6 The percentage of allowed cases here, 0.8.% cannot be directly compared to the "percent allowances" in Table 7. Table 8 is based on application status in PAIR, whereas Table 7 is based on the types of prosecution events. An application that receives a notice of allowance may end up being abandoned, appealed or remain pending, or patented.