The Federal Circuit recently vacated a District Court decision by Federal Circuit Judge Dyk, sitting by designation, based on erroneous claim construction in Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc.

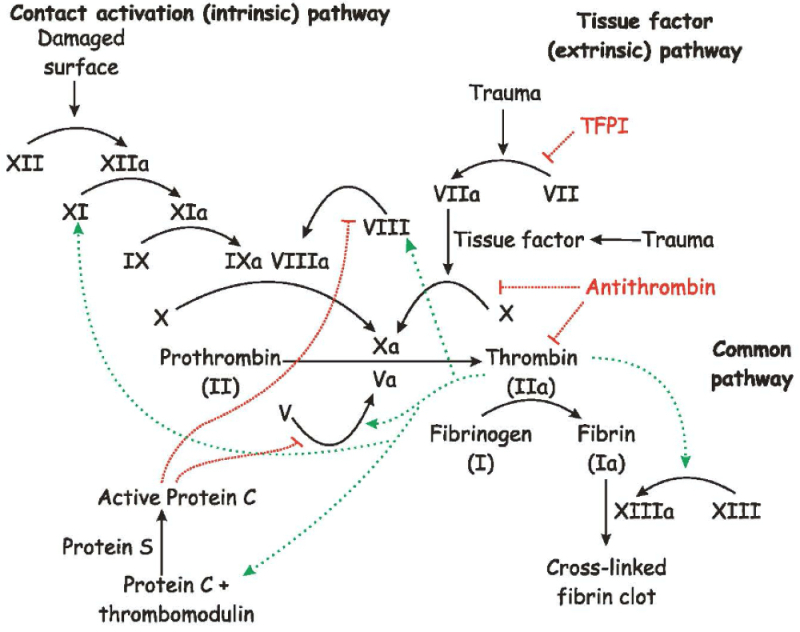

The case arose over Genentech's Hemlibra® (emicizumb-kxwh) product, which Baxalta alleged infringed its U.S. Patent No. 7,033,590. Baxalta asserted claims 1, 4, 17, and 19; these claims were directed to certain elements of the "blood clotting cascade" for treatment of hemophilia A. The invention claimed in the '590 patent involved using antibodies or antibody fragments to replace binding of Factor VIII (which is deficient or inhibited in hemophiliacs) to Factor IX, which permits restoration of the cascade (wherein Factor IX activates Factor X) as set forth in the following drawing:

The Federal Circuit found Claims 1, 4, and 19 to be illustrative:

1. An isolated antibody or antibody fragment thereof that binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

4. The antibody or antibody fragment according to claim 1, wherein said antibody or antibody fragment is selected from the group consisting of a monoclonal antibody, a chimeric antibody, a humanized antibody, a single chain antibody, a bispecific antibody, a diabody, and di-, oligo- or multimers thereof.

19. The antibody or antibody fragment according to claim 4, wherein the antibody is a humanized antibody.

At trial, the parties proposed alternative claim constructions for the terms "antibody" and "antibody fragment." Baxalta's proposed claim construction defined "antibody" as "[a] molecule having a specific amino acid sequence comprising two heavy chains (H chains) and two light chains (L chains)." Genentech's proposed construction was that "antibody" should be construed as "[a]n immunoglobulin molecule, having a specific amino acid sequence that only binds to the antigen that induced its synthesis or very similar antigens, consisting of two identical heavy chains (H chains) and two identical light chains (L chains)" (emphasis added). These differences were relevant because Genentech's Hemlibra® product was a bispecific antibody, i.e., the heavy and/or light chains comprising the antibody were different, thus permitting the two portions of the antibody to recognize and bind to different antigens. Judge Dyk, sitting by designation, held that the term "antibody," without more, could have different meanings to the skilled worker and both parties' definitions were consistent with these different meanings. In deciding to adopt Genentech's proposed construction, Judge Dyk held that Baxalta's specification contained a definition of the term that was dispositive:

Antibodies are immunoglobulin molecules having a specific amino acid sequence which only bind to antigens that induce their synthesis (or its immunogen, respectively) or to antigens (or immunogens) which are very similar to the former. Each immunoglobulin molecule consists of two types of polypeptide chains. Each molecule consists of large, identical heavy chains (H chains) and two light, also identical chains (L chains).

This definition was inconsistent with the remainder of the '590 specification, that disclosed bispecific antibodies, and also inconsistent with other naturally occurring antibody embodiments, such as IgM and IgA. Judge Dyk also dismissed the inconsistencies that this construction raised between claim 1 and claims 4 and 19 based in the one instance of express disclosure in the '590 specification. The District Court also relied on amendments made during prosecution of the '590 patent claims, wherein Baxalta amended claim 1 as filed to replace "antibody derivatives" with "antibody fragments." In Judge Dyk's view, these amendments amounted to a disclaimer of bispecific antibodies and limited the claims to antibody fragments.

With regard to the District Court's construction of the phrase "antibody fragments." Baxalta proposed construction of "[a] portion of a molecule having a specific amino acid sequence comprising two heavy chains (H chains) and two light chains (L chains)," whereas Genentech proposed to construe this term to mean "[a] fragment of an antibody which partially or completely lacks the constant region; the term 'antibody fragment' excludes all other forms of antibody derivatives." Again relying on express language in the specification ("antibody fragments . . . partially or completely lack the constant region" and identifying examples of fragments (Fv, Fab, Fab' [and] F(ab)'2)," Judge Dyk construed the phrase "antibody fragment" to mean "a fragment of an antibody which partially or completely lacks the constant region" and that "the term 'antibody fragment' excludes bispecific antibodies."

Based on these constructions, the parties stipulated that Genentech's Hemlibra® product did not infringe, and after the District Court entered judgment, Baxalta appealed.

The Federal Circuit vacated Judge Dyk's claim construction and final judgment and remanded, in an opinion by Judge Moore joined by Judges Plager and Wallach. The panel opinion reviewed Judge Dyk's construction de novo because the only evidence relied upon in Judge Dyk's decision was intrinsic evidence and thus the Federal Circuit owed the District Court no deference; see Teva Pharma. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 574 U.S. 318 (2015)). Under this standard, the Federal Circuit found that Judge Dyk erred in construing the term "antibody." Relying on the plain language of the claim (the first canon of claim construction under Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc); Judge Dyk joined 9 other Federal Circuit judges in this opinion), the Federal Circuit held that "nothing in the plain language of claim 1 limits the term "antibody" to a specific antibody consisting of two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains or an antibody that only binds the antigen that induced its synthesis or very similar antigens." The panel also opined that the dependent claims "confirm[ed] that [the term] "antibody" is not so limited," inter alia, wherein dependent (and asserted) claim 4 expressly recited a bispecific antibody as a species of antibody or antibody fragment. Construing a term in an independent claim to exclude expressly recited species in dependent claims is "inconsistent with the plain language of the claims," according to the panel, citing Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., 902 F.3d 1372, 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2018); and Ortho-McNeil Pharm., Inc. v. Mylan Labs., Inc., 520 F.3d 1358, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Genentech argued (at trial and before the Federal Circuit) that the proper outcome was to invalidate any such inconsistent dependent claims, which the panel refused to do based on the plain language of the claims.

Turning to the specification, the panel also rejected the District Court's reliance on specific disclosure set forth above. While acknowledging that, in isolation, that paragraph could be interpreted as providing a definition, "claim construction requires that we 'consider the specification as a whole, and . . . read all portions of the written description, if possible, in a manner that renders the patent internally consistent,'" citing Budde v. Harley-Davidson, Inc., 250 F.3d 1369, 1379–80 (Fed. Cir. 2001). Judge Dyk's use of the specification to support his claim construction was also inconsistent with the practice of the Court, inter alia, because this excerpt is devoid of language that renders such "general statements" limiting, as set forth, for example, in Luminara Worldwide, LLC v. Liown Elecs. Co., 814 F.3d 1343, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2016). Considering the specification as a whole, the panel notes that it contains "specific disclosures regarding bispecific, chimeric, and humanized antibodies and methods of production thereof," all of which rebut the District Court's construction. The specification also expressly discloses methods for producing humanized or chimeric antibodies which are also inconsistent with Judge Dyk's claim construction.

Finally, the Federal Circuit considered the prosecution history and concluded that it did not support the District Court's claim construction based on prosecution history disclaimer. According to the panel, the disclaimer perceived by Judge Dyk was not "sufficiently clear and unmistakable" to amount to clear disclaimer, citing 3M Innovative Properties Co. v. Tredegar Corp., 725 F.3d 1315, 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2013). The District Court's construction was also inconsistent with allowance of claim 4, which expressly recites bispecific antibody fragments.

The panel concludes by mandating the construction to be used on remand, wherein "antibody" is construed to mean "an immunoglobulin molecule having a specific amino acid sequence comprising two heavy chains (H chains) and two light chains (L chains)."

Turning to construction of the phrase "antibody fragments," the Federal Circuit held Judge Dyk erred in his construction of this term, and held that on remand the phrase be construed to mean "[a] portion of an immunoglobulin molecule having a specific amino acid sequence comprising two heavy chains (H chains) and two light chains (L chains)." The Federal Circuit based its finding of error on the District Court's reliance on a portion of the specification that recited:

The term factor IX/IXa activating antibodies and antibody derivatives may also include . . . e.g., "technically modified antibodies" such as synthetic antibodies, chimeric or humanized antibodies, or mixtures thereof, or antibody fragments which partially or completely lack the constant region, e.g. Fv, Fab., Fab' or F(ab) etc.

The error was in confining claims to specific embodiments recited in the specification, about which the opinion states the court "has repeatedly warned against," citing Thorner v. Sony Comput. Entm't Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012). The panel also notes that the specification contained language ("may also include," "e.g.," "such as," and "etc.") indicting that the patentee did not intend to provide a limiting definition of the phrase "antibody fragments."

Thus, the Federal Circuit remanded the action back to the District Court, awarding costs to Baxalta.

Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2020)

Panel: Circuit Judges Moore, Plager, and Wallach

(note: after oral argument, Judge Plager replaced Judge Stoll, who recused)

Opinion by Circuit Judge Moore