In 1984, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Rep. Henry Waxman (D-CA) shepherded a grand legislative compromise through Congress that balanced the rights and solved inefficient regulatory consequences for both branded and generic drug makers. Forever known as the Hatch-Waxman Act (formally, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act), certain of the provisions created a safe harbor for generic drugs to be tested for purposes related to regulatory approval without incurring infringement liability (codified at 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)) as well as a pathway for generic drug makers to challenge patents listed by branded drug makers as being non-infringed, invalid, or unenforceable and litigation (ANDA litigation) to resolve these allegations (codified at codified at 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)). For branded drug makers, the Act provided for extension of patent term (PTE) to make up for regulatory delay in obtaining marketing approval (codified at 35 U.S.C. § 156 et seq.). Litigation has ensued robustly under § 271(e)(2) and PTE's obtained by numerous branded drugs in the 35+ years since enactment of the Hatch-Waxman Act, but the proper application of the Act with regard to PTE provisions continued to be litigated, most recently in Biogen Int'l v. Banner Life Sciences LLC (ANDA litigation is almost a patent law specialty, for good or ill; see "Yet Another Study Suggesting Changes in Hatch-Waxman Regime").

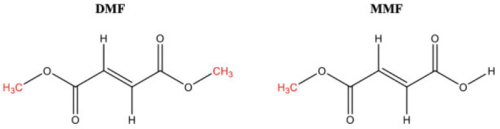

The case arose in an infringement action by Biogen asserting U.S. Patent No. 7,619,001 against Banner over Banner's application under 21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(2) (a § 505(b)(2) application) for its generic version of Biogen's Tecfidera® (dimethylfumarate), a drug for treating multiple sclerosis. As set forth in the Federal Circuit's opinion, DMF is metabolized to the monomethyl form (MMF), as illustrated in this figure:

Claim 1 of the '001 patent was considered representative by the Court:

1. A method of treating multiple sclerosis comprising administering, to a patient in need of treatment for multiple sclerosis, an amount of a pharmaceutical preparation effective for treating multiple sclerosis, the pharmaceutical preparation comprising at least one excipient or at least one carrier or at least one combination thereof; and dimethyl fumarate, methyl hydrogen fumarate, or a combination thereof.

Importantly for the issues before the Court, Banner obtained its approval for the monomethyl form, which would be infringing as being recited in the '001 patent claims if and only if the '001 was entitled to extension of term for this drug. As set forth in more detail below in the context of the Federal Circuit opinion, PTE is limited to claims that encompass the approved drug and extended claims can be asserted only against infringement for drugs subject to FDA approval.

The District Court granted Banner's motion to dismiss under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(c) on the grounds that the PTE did not apply to Banner's product because, while encompassed by the '001 patent claims, those claims were not entitled to PTE because MMF was not the drug approved by the FDA for which Biogen was entitled to PTE for regulatory delay. The District Court rejected Biogen's argument that, for method claims, the extension applied to any approved drug that fell within the scope of the claim. This appeal followed.

The Federal Circuit affirmed, in an opinion by Judge Lourie joined by Judges Moore and Chen. The Court based its affirmance on its interpretation of the statute, specifically that "the scope of a patent term extension under 35 U.S.C. § 156 only includes the active ingredient of an approved product, or an ester or salt of that active ingredient, and the product at issue does not fall within one of those categories." The issue for the Court was the proper interpretation of § 156(f), which "defines "product" as "the active ingredient of . . . a new drug . . . including any salt or ester of the active ingredient." § 156(f)(2)(A).

Biogen in arguing against the District Court's decision cites Pfizer Inc. v. Dr. Reddy's Labs., Ltd., 359 F.3d 1361 (Fed. Cir. 2004) for the proposition that "product" encompasses "the de-esterified form [here, MMF], particularly where 'a later applicant's patentably indistinct drug product . . . relies on the patentee's clinical data'" (which was the case for Banner's application under § 505(b)(2)). Biogen contended the term "active ingredient" meant "active moiety" and the proper interpretation was not governed by Glaxo Ops. UK Ltd. v. Quigg, 894 F.2d 392, 395 (Fed. Cir. 1990), which Banner argued excluded de-esterified forms of an active ingredient.

The Federal Circuit rejected both parties' recourse to case law and relied on the plain meaning of the statute. According to the Court, the term "active ingredient" has a specific definition as "any component that is intended to furnish pharmacological activity or other direct effect," citing 21 C.F.R. § 210.3(b)(7). It also "must be present in the drug product when administered," citing Hoechst-Roussel Pharm., Inc. v. Lehman, 109 F.3d 756, 759 n.3 (Fed. Cir. 1997), and is itself defined by what the FDA approved and is specified on the drug label under 21 U.S.C. § 352(e)(1)(A)(ii); 21 C.F.R. § 201.100(b)(4).

Here, MMF is not the approved product and is not specified on the label, and thus Banner's activities (which would have been infringing before expiry of the unextended term of the patent) were not infringing because, as to its embodiments, the '001 patent had expired.

Interestingly, while the statute expressly encompasses esters in the definition of an active ingredient, de-esterified active ingredients like MMF are not. Thus the Federal Circuit established a well-defined (perhaps arising to a "bright line") rule that:

All these precedents, and now this case, rest on the same holding: the term "product," defined in § 156(f) as the "active ingredient . . . including any salt or ester of the active ingredient," has a plain and ordinary meaning that is not coextensive with "active moiety." It encompasses the active ingredient that exists in the product as administered and as approved—as specified by the FDA and designated on the product's label—or changes to that active ingredient which serve only to make it a salt or an ester. It does not encompass a metabolite of the active ingredient or its deesterified form.

Biogen Int'l v. Banner Life Sciences LLC (Fed. Cir. 2020)

Panel: Circuit Judges Lourie, Moore, and Chen

Opinion by Circuit Judge Lourie