The Federal Circuit extended the scope of the judicially created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (OTDP) in a split decision rendered in Gilead Sciences Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd. In doing so, the panel majority applied what it viewed as the important policy motivations for the doctrine, a rationale unpersuasive to the Chief Judge in dissent.

The Federal Circuit extended the scope of the judicially created doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting (OTDP) in a split decision rendered in Gilead Sciences Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd. In doing so, the panel majority applied what it viewed as the important policy motivations for the doctrine, a rationale unpersuasive to the Chief Judge in dissent.

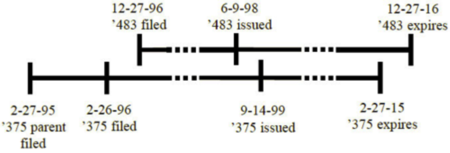

The case involved antiviral drugs and methods directed to influenza virus as claimed in U.S. Patent Nos. 5,763,483 and 5,952,375. These patents were commonly owned, named the same inventors, and were directed to related subject matter (interference with viruses by "selective interference with certain enzymes"), but did not share any priority relationship and had different filing and expiration dates set forth by the Court as follows:

As shown, the earlier issued application expires later than later-filed application.

The lawsuit arose under the provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2) upon filing of Natco's Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Gilead sued, the parties stipulated infringement, and the issue before the District Court was whether Gilead's '483 patent was invalid for OTDP in view of the earlier-filed '375 patent. Gilead filed a terminal disclaimer in the '375 patent with regard to the '483 patent (something that the Court noted "would not occur since, as explained above, the '375 patent's expiration date is before the '483 patent's expiration date" absent abandonment), but no terminal disclaimer was filed in the '483 patent, and separate examiners were not informed of the existence of the other application otherwise. According to the opinion, Gilead "crafted a separate 'chain' of applications having a later priority date than the '375 patent family," which provides a hint early in the opinion that the panel majority was attempting to prevent Gilead from avoiding OTDP strategically. The District Court determined that the extensions in patent term were "not a result of gamesmanship, but instead were a result of changes to [the] patent laws" attendant upon ratification of the GATT treaty.

The lawsuit arose under the provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2) upon filing of Natco's Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Gilead sued, the parties stipulated infringement, and the issue before the District Court was whether Gilead's '483 patent was invalid for OTDP in view of the earlier-filed '375 patent. Gilead filed a terminal disclaimer in the '375 patent with regard to the '483 patent (something that the Court noted "would not occur since, as explained above, the '375 patent's expiration date is before the '483 patent's expiration date" absent abandonment), but no terminal disclaimer was filed in the '483 patent, and separate examiners were not informed of the existence of the other application otherwise. According to the opinion, Gilead "crafted a separate 'chain' of applications having a later priority date than the '375 patent family," which provides a hint early in the opinion that the panel majority was attempting to prevent Gilead from avoiding OTDP strategically. The District Court determined that the extensions in patent term were "not a result of gamesmanship, but instead were a result of changes to [the] patent laws" attendant upon ratification of the GATT treaty.

The Federal Circuit vacated the District Court's judgment of infringement and remanded for reconsideration of Natco's invalidity contentions; notably, the opinion states that "[f]or purposes of this appeal, we assume that the '483 patent claims a mere obvious variant of the invention claimed in the '375 patent" because the District Court did not reach the merits. The decision for the majority was penned by Judge Chen joined by Judge Prost, with Chief Judge Rader dissenting.

The question the majority considered was before it was:

Can a patent that issues after but expires before another patent qualify as a double patenting reference for that other patent?

The majority answered this question "yes" under the circumstances of this case. In a nutshell:

Because the obviousness-type double patenting doctrine prohibits an inventor from extending his right to exclude through claims in a later-expiring patent that are not patentably distinct from the claims of the inventor's earlier-expiring patent, we agree with Natco that the '375 patent qualifies as an obviousness-type double patenting reference for the '483 patent.

The panel majority began its analysis by citing several Supreme Court cases (Miller v. Eagle Mfg. Co., 151 U.S. 186, 197-98, 202 (1894); Suffolk Co. v. Hayden, 70 U.S. 315, 317 (1865), and particularly Justice Story riding the First Circuit at Odiorne v. Amesbury Nail Factory, 18 Fed. Cas. 578, 579 (C.C.D. Mass. 1819)) for the proposition that the patent grant is balanced by the invention falling into the public domain once the patent expires, which implicates judicial prohibitions against extending the patent term that the OTDP prohibition is intended to impose. This included not only serial patents on the same invention but also a prohibition on patents reciting patentably indistinct inventions, i.e., ones that claimed only an "obvious modification[]" of a patented invention. The majority cited 35 U.S.C. § 253 as changing the scope of the OTDP doctrine, permitting separate patents provided that the patentee disclaimed later term, citing Application of Robeson, 331 F.2d 610, 614 (CCPA 1964), which is "tantamount for all practical purposes to having all the claims in one patent." Application of Braithwaite, 379 F.2d 594, 601 (CCPA 1967).

The majority bases its decision that OTDP applies in this situation on the "bedrock principle" that "when a patent expires, the public is free to use not only the same invention claimed in the expired patent but also obvious or patentably indistinct modifications of that invention." However:

[T]hat principle is violated when a patent expires and the public is nevertheless barred from practicing obvious modifications of the invention claimed in that patent because the inventor holds another later-expiring patent with claims for obvious modifications of the invention. Such is the case here.

Because the panel majority believes that the claims of the '483 patent are mere obvious variants of the claims in the '375 patent, they find that, if the claims of the '483 patent are patentably indistinct from the claims of the '375 patent, then the term of the '483 patent should end on the same date as the '375 patent expires (keeping in mind that neither the District Court nor the majority have yet made that determination).

The panel majority rejected Gilead's argument that extending the term of the '483 patent was not the issue, because that patent issued earlier than the '375 patent. This argument garnered no traction with the panel majority in view of the policy reasons underlying their decision. The panel acknowledged disruptions caused by the GATT treaty in the traditional term relationships between patents, stating that "the focus on controlling the patent term of later issued patents in those [earlier] cases [cited by Gilead] makes perfect sense: before the URAA [GATT}, later issued patents expired later" (emphasis in opinion). Patent issue dates under the prior regime "served as a reliable stand-in for the date that really mattered" to the panel: the patent expiration date at which time the invention fell into the public domain. Doing otherwise would encourage "significant gamesmanship" during prosecution, according to the panel majority, setting out the scenario that:

[I]f the double patenting inquiry was limited by issuance date, inventors could routinely orchestrate patent term extensions by (1) filing serial applications on obvious modifications of an invention, (2) claiming priority to different applications in each, and then (3) arranging for the application claiming the latest filing date to issue first. If that were to occur, inventors could potentially obtain additional patent term exclusivity for obvious variants of their inventions while also exploring the value of an earlier priority date during prosecution.

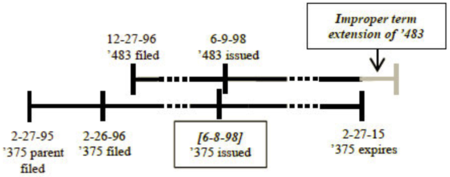

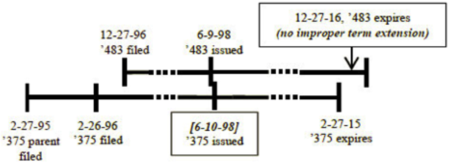

Such gamesmanship is illustrated by the change in whether or not OTDP applies based on whether the first filed application granted as a patent one day before or one day after the later-filed application:

versus

These differences are "simply too arbitrary, uncertain, and prone to gamesmanship" in the panel majority's view, and the majority opined that "Congress could not have intended to inject the potential to disturb the consistent application of the doctrine of double patenting by passing the URAA."

Thus, the majority fashioned a rule that "the earliest expiration date of all the patents an inventor has on his invention and its obvious variants" should be used for the District Court's OTDP analysis, saying that "[p]ermitting any earlier expiring patent to serve as a double patenting reference for a patent subject to the URAA guarantees a stable benchmark that preserves the public's right to use the invention (and its obvious variants) that are claimed in a patent when that patent expires."

Chief Judge Rader dissented in an opinion where he characterized the majority's decision as unnecessarily "expand[ing] the judicially-created doctrine of OTDP." While agreeing with the majority that "the doctrine has served a useful purpose over the years" under U.S. patent law prescribing a patent term of 17 years from patent grant date, under current law the Chief does not apprehend that the rationale behind the OTDP doctrine still exists. In his view, "a primary motivation behind the doctrine -- preventing the effective extension of patent term -- is largely no longer applicable." The Chief Judge does recognize what he terms "a second underlying policy concern -- preventing multiple infringement suits by different assignees asserting essentially the same patented invention." But he does not believe this concern is implicated in this case, either.

In his dissent the Chief Judge notes a logical inconsistency in the majority's argument, that if the '375 patent had never issued, Gilead would have been entitled to the full extent of the '483 patent term. Thus, the issue can be considered not as the majority has, that the term of the '483 patent is improperly extended past the expiration date of the earlier-filed '375 patent, but rather whether an earlier-issued patent's term can be cut short by later grant of an earlier-filed application (which the majority sanctioned here). And he noted that Gilead conformed to the statutory regime regarding priority and did not claim priority in the later-filed '483 patent to the related disclosure (and priority date) of the earlier-filed '375 patent. In doing so, Gilead "forfeit[ed] its earlier claim to priority and subject[ed] any new patent to intervening prior art," perhaps the antithesis of gamesmanship (giving up about 10 months of priority according to the Chief).

With regard to the majority's stated view, he recites what he believes to be "the flawed assumption that upon the expiration of a patent, the public obtains an absolute right to use the previously-claimed subject matter." The Chief Judge notes that "even a patentee [does not] have the affirmative right to use its claimed subject matter," citing Spindelfabrik Suessen-Schurr, Stahlecker & Grill GmbH v. Schubert & Salzer Maschinefabrik Aktiengesellschaft, 829 F.2d 1075, 1081 (Fed. Cir. 1987). In addition, he argues, this assumption "ignores the possible existence of overlapping patents" (such as a first patent to a genus and a later patent to a species; this argument ignores the requirement that said later species be patentably distinct from the genus). In addition to generally counseling his brethren that judicial restraint in extending judicially created patent doctrines is the more prudent path, the Chief Judge also noted the potential for unforeseen effects of the majority's decision on filing behavior under the "first-inventor-to-file" provisions of the America Invents Act.

Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2014)

Panel: Chief Judge Rader and Circuit Judges Prosy and Chen

Opinion by Circuit Judge Chen; dissenting opinion by Chief Judge Rader.