"This is not how patent law works."

[author: Andrew Williams]

Writing for the majority in Alcon Research, Ltd. v. Apotex Inc. last Wednesday, Judge Moore took issue with a position advanced by Alcon's counsel that would have essentially allowed a court to rewrite patent claims to preserve validity. Because of that, in part, the Federal Circuit reversed a lower court's finding of non-obviousness with regard to six claims of the patent covering PANTANOL®. However, because the Court affirmed the validity of two narrower dependent claims, Novartis' Alcon unit retained the ability to block generic competition of its anti-allergy eye-drops.

Writing for the majority in Alcon Research, Ltd. v. Apotex Inc. last Wednesday, Judge Moore took issue with a position advanced by Alcon's counsel that would have essentially allowed a court to rewrite patent claims to preserve validity. Because of that, in part, the Federal Circuit reversed a lower court's finding of non-obviousness with regard to six claims of the patent covering PANTANOL®. However, because the Court affirmed the validity of two narrower dependent claims, Novartis' Alcon unit retained the ability to block generic competition of its anti-allergy eye-drops.

The technology at issue in the Alcon case was the drug product olopatadine, which is used in PANTANOL® to treat allergic eye disease in humans. As background, antigens can cause the formation of antibodies in the body, and these antibodies can then bind to the surface of mast cells (which are specialized cells that are involved in the allergic reaction). Such binding causes the sensitization of the mast cells, such that any subsequent antigen binding causes the cells to release chemical mediators, such as histamine and heparin. To treat allergic reactions, anti-allergy drugs can interfere at multiple points in this process. One such class of drugs is the mast cell stabilizers, which prevent the mast cells from releasing these mediators, thereby reducing the allergic symptoms. In the human eye, mast cells are located in the membrane that covers the inner surface of the eyelid and the white part of the eyeball (the conjunctiva).

The technology at issue in the Alcon case was the drug product olopatadine, which is used in PANTANOL® to treat allergic eye disease in humans. As background, antigens can cause the formation of antibodies in the body, and these antibodies can then bind to the surface of mast cells (which are specialized cells that are involved in the allergic reaction). Such binding causes the sensitization of the mast cells, such that any subsequent antigen binding causes the cells to release chemical mediators, such as histamine and heparin. To treat allergic reactions, anti-allergy drugs can interfere at multiple points in this process. One such class of drugs is the mast cell stabilizers, which prevent the mast cells from releasing these mediators, thereby reducing the allergic symptoms. In the human eye, mast cells are located in the membrane that covers the inner surface of the eyelid and the white part of the eyeball (the conjunctiva).

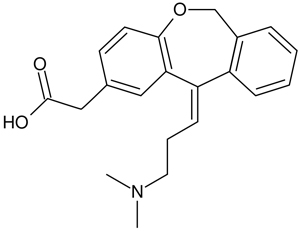

The drug product olopatadine was known in the prior art as an effective antihistamine, and chemicals related to olopatadine that were known to have mast cell stabilizing activity. However, olopatadine was not known to stabilize mast cells. Moreover, mast cells from different species, and even different tissue from the same species, can have different biological responses, referred to as mast-cell heterogeneity. Therefore, even though the drug was already known in the art, Alcon's scientists were the first to show that olopatadine could stabilize conjunctival mast cells in humans using in vitro testing. This work gave rise to U.S. Patent No. 5,641,805 ("the '805 patent"), which claimed methods for treating allergic eye diseases in humans by topically administering an olopatadine composition. The claims of this patent required that this method be accomplished by stabilizing the conjuctival mast cells. Alcon's PANTANOL® product is the commercial embodiment of the claims of the '805 patent.

The present action began when Apotex filed an ANDA seeking permission to sell a generic version of PANTANOL®, which included a Paragraph IV certification against the '805 patent. In turn, Alcon sued Apotex in the Southern District of Indiana. The lower court held that Apotex failed to establish by clear and convincing evidence that the claims of the '805 patent were obvious over the prior art. One of the reasons was that, even though olopatadine was known to be an effective antihistamine, there were significant barriers to adapting a systemic antihistamine for topical use in the eyes. In addition, the prior art did not teach that olopatadine could act as a mast cell stabilizer. Finally, the lower court found that objective evidence of non-obviousness, including unexpected results, long-felt need, and commercial success, supported its holding. Apotex appealed.

The present action began when Apotex filed an ANDA seeking permission to sell a generic version of PANTANOL®, which included a Paragraph IV certification against the '805 patent. In turn, Alcon sued Apotex in the Southern District of Indiana. The lower court held that Apotex failed to establish by clear and convincing evidence that the claims of the '805 patent were obvious over the prior art. One of the reasons was that, even though olopatadine was known to be an effective antihistamine, there were significant barriers to adapting a systemic antihistamine for topical use in the eyes. In addition, the prior art did not teach that olopatadine could act as a mast cell stabilizer. Finally, the lower court found that objective evidence of non-obviousness, including unexpected results, long-felt need, and commercial success, supported its holding. Apotex appealed.

Claims 1-3 and 5-7 Were Obvious

The Federal Circuit disagreed with the lower court's determination that claims 1-3 and 5-7 were not obvious over the prior art. The amount of administered olopatadine covered by the specific claims was important to this decision. Independent claim 1 read:

1. A method for treating allergic eye diseases in humans comprising stabilizing conjuctival mast cells by topically administering to the eye a composition comprising a therapeutically effective amount of 11-(3-dimethylaminopropylidene)-6,11-dihydrodibenz(b,e)oxepin-2-acetic acid or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof.

(emphasis added). The dependent claims specified the amount of administered olopatadine, ranging from about 0.0001% w/v to 5% w/v (claims 2 and 6) to about 0.001% to about 0.2% w/v (claims 3 and 7). The Federal Circuit reasoned that "a therapeutically effective amount" could not be a range less than 0.0001% w/v to 5% w/v, because a dependent claim cannot be broader than a claim from which it depends. With regard to the range of administered olopatadine covered by the claims, Alcon's counsel took the position that the claims required that conjuctival mast cells be stabilized, and therefore any part of the range recited in the claim that does not operate to achieve this requirement would not fall within the scope of the claim. Of course, as the Court pointed out, patent law does not work this way. Instead, if you claim a range, and part of the range is inoperative (i.e., not enabled), you cannot later disavow the invalid portion. "Courts do not rewrite the claims to narrow them for the patentee to cover only the valid portion." Alcon, slip op. at 12.

With regard to the obviousness contentions, the main reference cited against these claims was the Kamei reference, which disclosed treating eye allergies in guinea pigs using olopatadine at concentrations ranging from 0.0001% w/v to 0.01% w/v. This range overlapped the range of claims 1-3 and 5-7 of the '805 patent. Therefore, the only question for the Federal Circuit was whether there was a motivation to adapt this teaching to a use for treating allergic eye disease in humans. The Court found that the lower court erred by only looking to the '805 patent for this motivation. Instead, the Federal Circuit found that such motivation existed because the guinea pig animal model was predictive of antihistaminic efficacy in humans (a fact found by the lower court). The Federal Circuit did find that the lower court's determination that Kamei did not teach olopatadine as a mast cell stabilizer was not clear error, but nevertheless Kamei's teaching of the use of olopatadine with "overlapping concentrations, even if for a different purpose, meets these claim limitations," even without that teaching.

Important to the Court's analysis was the effect of the claim phrase: "stabilizing conjuctival mast cells." The lower court had construed this term to limit the claims to concentrations of olopatadine that so stabilize mast cells, and that are clinically relevant. The Federal Circuit stated that it was not deciding whether this construction was correct. However, as pointed out above, to the extent this construction allowed a disavowal of inoperative claim scope, the Court noted that this could not be correct. In fact, the Federal Circuit's opinion essentially read this claim term out of the claim, because it found that it was not necessary for the prior art to teach this mast-cell stabilizing effect. The reason provided was that the claim language did not impose any additional requirements beyond the cited range of administered olopatadine because the '805 patent taught that mast cell stabilization necessarily occurred at the claimed concentrations. This allowed the Court to side-step the issue of whether an inherent property of the prior art could be used in an obviousness determination. This was analogized to the situation in In re Kubin, 561 F.3d 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2009). In that case, the applicants were attempting to claim an isolated nucleic acid molecule that encoded the Natural Killer Cell Activation Inducing Ligand ("NAIL"). However, the claim also included the limitation that the polypeptide bind CD48, which was not known in the prior art:

73. An isolated nucleic acid molecule comprising a polynucleotide encoding a polypeptide at least 80% identical to amino acids 22-221 of SEQ ID NO:2, wherein the polypeptide binds CD48.

Nevertheless, because the patent application in Kubin explained that CD48 binding was an inherent property of NAIL, the prior art's failure to mention this was irrelevant to a finding that the claim was obvious.

The Federal Circuit stressed the point that these cases did not implicate inherency. However, if a property is not taught in the prior art, but the patent teaches that this property is necessarily present, it is unclear how this is different than inherency. The distinction that the Court made -- that it was the patent that taught the inherent property -- does not appear to be relevant. The problem that the Court faced was in acknowledging that the property was inherent, they would have to acknowledge that this was a case of inherent obviousness -- something that the Federal Circuit does not like to do.

Claims 4 and 8 Affirmed as Non-obvious

With regard to the remaining two claims, claims 4 and 8, the Federal Circuit found that Kamei could not be used to render them obvious. Both of these claims required the administration of olopatadine at a concentration of 0.1% w/v. Kamei only tested olopatadine to a concentration of 0.01% w/v. The Federal Circuit could not say that the lower court erred in finding that Kamei did not teach or suggest the higher concentration. Apotex had also argued that a second reference, Lever, taught the use of a different ophthalmic formation at the concentration or 0.1% w/v. However, a person of ordinary skill would not assume that you could simply substitute active ingredients in a formulation without adjusting concentrations. Finally, PANTANOL® achieved nearly 70% market share within two years, and therefore the finding of commercial success was not clearly erroneous. At the end of the day, therefore, Alcon was left with two valid claims, and as a result, Apotex will not be able to receive approval to market a generic version of PANTANOL® before the expiration of the '805 patent.

Alcon Research, Ltd. v. Apotex Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2012)

Panel: Circuit Judges Prost, Moore, and O'Malley

Opinion by Circuit Judge Moore