Key Takeaways

- Patents are increasingly being used to protect innovation in the food technology space.

- Food technology companies should carefully decide whether to use patents or trade secrets to protect their proprietary assets.

- Food technology is a global industry and the countries selected for trademark registration provide a hint as to where companies foresee future success for the industry.

- Disputes in the field underscore the importance of having a strong intellectual property strategy.

The food technology industry has grown rapidly in recent years, reaching an estimated $8 billion in 2022, according to the Good Food Institute. As food tech companies continue to innovate, expand, and enter new markets, it is essential that they develop a cohesive intellectual property (IP) strategy to protect their critical assets.

There are four main types of intellectual property: patents, trademarks, trade secrets, and copyrights. A company can protect its proprietary technology using patents, which grant exclusive rights to an invention, or trade secrets, which can include any type of confidential information. A company can protect its brand using trademarks, which are used to protect words, phrases, designs, or a combination of these that identify a company’s product. This article will focus on IP protection, using patents, trade secrets, and trademarks. However, copyrights can also be used to protect a company’s intellectual assets, including packaging, commercials, and other ads.

Patents

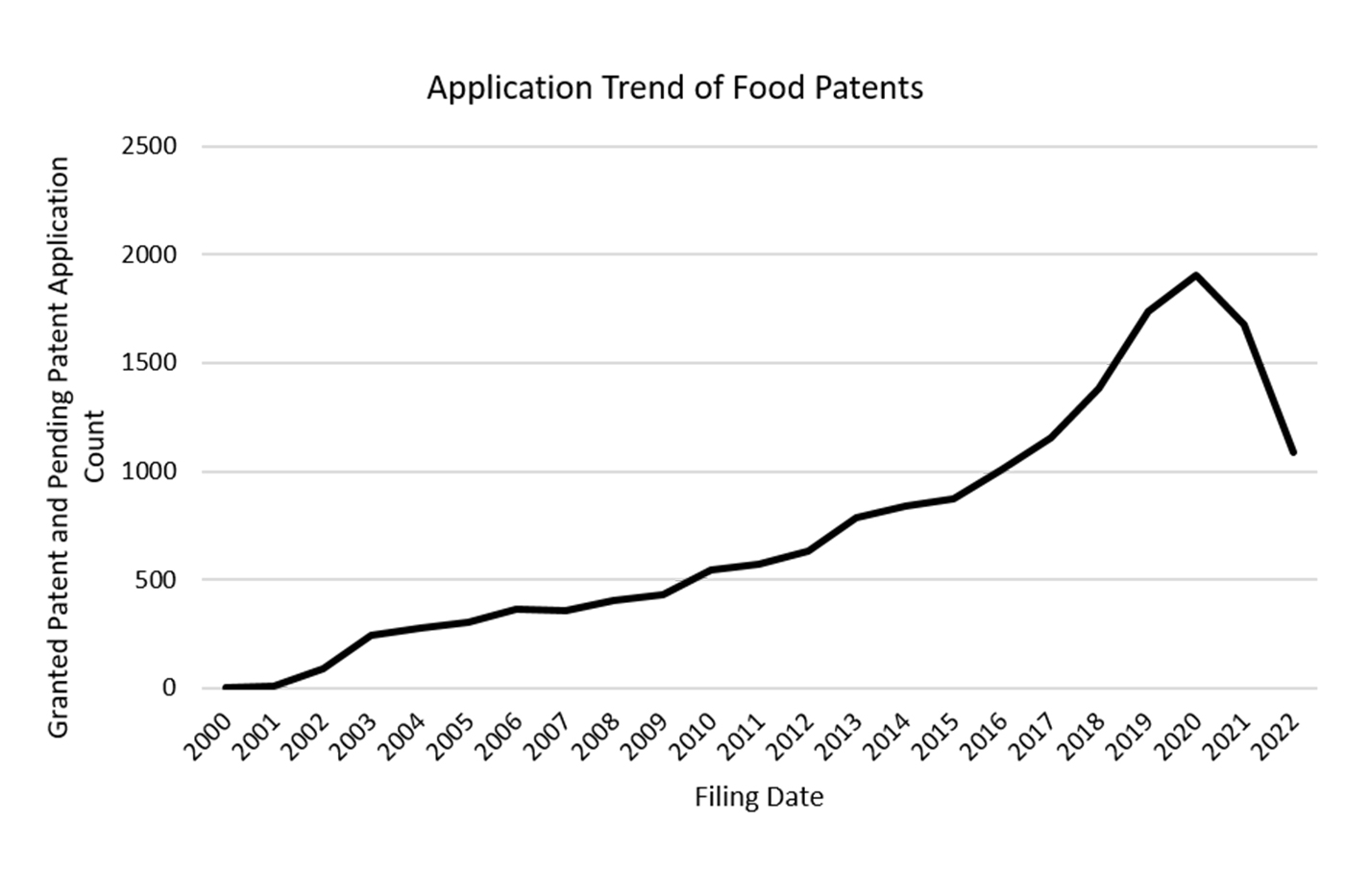

While the food industry has historically relied on trade secrets and trademarks for protection, over the last decade there has been an increase in patent filings in this space. A technology qualifies for patent protection when it is new, useful, functional, and innovative. For example, inventing a way to grow food-grade meat in a lab without raising a chicken is patentable as long as it is not an obvious step to take based on previously existing technologies.

Source: Search of U.S. and WIPO patent database on Aug. 21, 2023 (patent and patent application results generated using the keyword query: IPC:(A23) AND SIMPLE_LEGAL_STATUS:(1 OR 2) NOT IPC:(B OR D OR E OR F OR H OR A01 OR A21 OR A22 OR A24)) for granted patents and pending patent applications in the “Food or Foodstuffs…” category excluding agriculture, packaging, etc.

Source: Search of U.S. and WIPO patent database on Aug. 21, 2023 (patent and patent application results generated using the keyword query: IPC:(A23) AND SIMPLE_LEGAL_STATUS:(1 OR 2) NOT IPC:(B OR D OR E OR F OR H OR A01 OR A21 OR A22 OR A24)) for granted patents and pending patent applications in the “Food or Foodstuffs…” category excluding agriculture, packaging, etc.

Interestingly, we are also starting to see an increase in litigation in this space due to parallel developments of similar technology. Impossible Foods filed the first ever food tech U.S. patent infringement lawsuit in the United States in March 2022 against defendant Motif FoodWorks.1 In response, Motif filed a motion to dismiss the case and parallel inter partes review (IPR) petitions at the Patent and Trademark Appeal Board (PTAB) related to the same patents that Impossible asserted against it in the district court case, arguing that Impossible’s patents should not have been granted in the first place. The district court judge denied Motif’s motion to dismiss,2 which means that Motif and Impossible are set to continue the battle in district court. Motif and Impossible will also be fighting it out at the PTAB, which agreed to institute an IPR to examine one of Impossible’s U.S. patents, U.S. Patent No. 9,943,096 (IPR2023-00209).

Meanwhile, Impossible also faces challenges to its patent portfolio in Europe in the form of an opposition at the European Patent Office (EPO). Reiser & Partner Patentanwälte mbB, a German patent law firm, requested reexamination of Impossible’s patent EP2943072 in 2018 and the patent was revoked on December 19, 2022. However, Impossible filed a Notice of Appeal (No. T0425/23) with the EPO on February 17, 2023, the results of which are pending.

Food tech companies should consider the outcomes to the challenges of the Impossible patents in the strategic planning of their own patent portfolios and general IP strategy. For example, if Impossible is victorious, companies who use hemeprotein technologies may consider licensing Impossible’s patents as they develop new plant-based meat products. If Impossible loses these challenges, early entrants to their respective food tech fields may consider reevaluating the strength of their patents and whether they would stand up to a challenge from a direct competitor.

Trade Secrets

The food and beverage industry has historically used trade secrets to protect proprietary assets. Heinz ketchup’s secret recipe, Campari’s blend of herbs and spices, and Coca-Cola’s secret formula are all protected as trade secrets. Recently, there has been a wave of new laws and regulations around the world—for example, in the European Union, China, Japan, and the United States—strengthening trade secret protections and making it appealing for food companies to continue to protect proprietary assets as trade secrets.

On the one hand, there are several advantages for a food tech company to protect proprietary assets as trade secrets. For example, a trade secret owner does not have to establish that the protected information meets a country’s statutory requirements for patent protection or disclose the proprietary information. Additionally, patents have a time limit, for example 20 years in the United States, while trade secrets can be protected indefinitely. On the other hand, proprietary assets would no longer be eligible for trade secret protection if a competitor is able to independently develop or reverse engineer a company’s secret information. Also, a company can only protect proprietary information as trade secrets if it can prove that it took the statutorily required steps to protect the information as trade secrets, while granted patents enjoy a presumption of validity.

The advantages and potential pitfalls of protecting proprietary assets as trade secrets instead of as patents are illustrated in a recent lawsuit. Two food tech startups developing fungi-based meat alternatives are currently embroiled in a lawsuit regarding theft of trade secrets and the inventorship of a patent owned by The Better Meat Co. (U.S. Patent No.11,058,137 or “the ’137 patent”). Meati Foods argued that the ’137 patent describes Meati’s trade secret and confidential information that was stolen by The Better Meat Co., and that its scientists should be listed as inventors in the ’137 patent. The Better Meat Co. argued that Meati has not shown that it stole the technology covered by the ’137 patent, and Meati cannot stop The Better Meat Co. from practicing its own granted patent.3 This case is currently ongoing and no definitive decision regarding the patent inventorship or trade secret misappropriation issues have been decided so far.4

Trademarks

Another way to protect a company’s intellectual property is by applying for trademarks, which safeguards a brand’s commercial identity by preventing others from adopting a similar name or logo. A company can obtain a trademark through use in a specific geographical area alone (common law trademark) or through registration. The Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property is an international treaty that provides a path for a company to file a trademark application with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), based on a trademark registered in its home country, and enter national stage registration in any of the Paris Convention’s over 150 signatory countries.

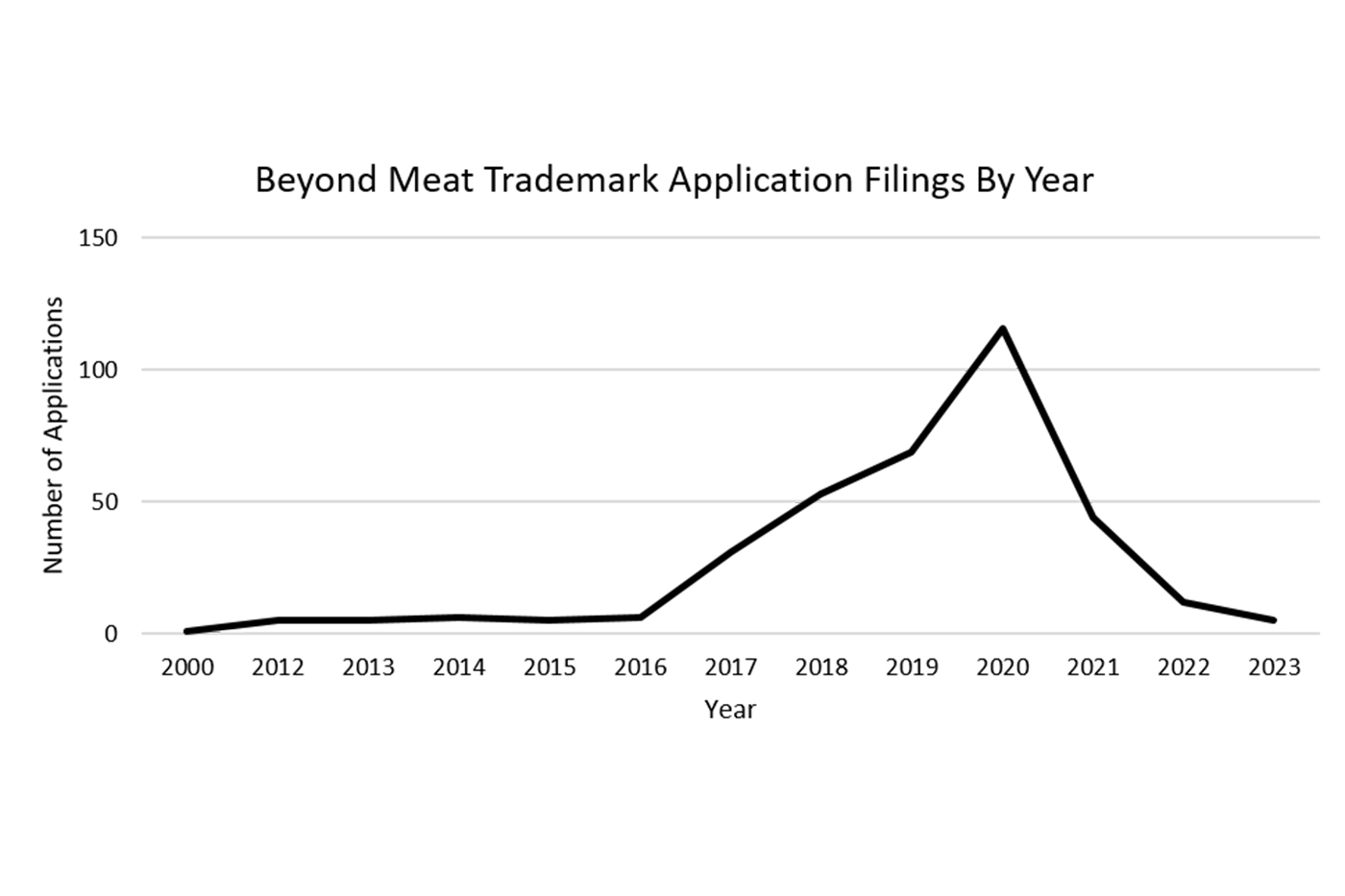

Beyond Meat is a plant-based meat company founded in 2009 and is one of the earliest entrants to the plant-based meat market. It is one of the most recognizable brands in the plant-based meat industry, and its commercial success led it to be the first plant-based meat company to go public in 2019.5 According to the WIPO’s Global Brand Database, it first started to register for trademark protection in 2000. Currently, Beyond has 200 registered trademarks and 61 pending applications and the top two countries to which it has designated its trademark applications for national entry are the United States and the United Kingdom. Interestingly, Beyond also started filing trademark applications for Beyond Milk in 2021, signaling its intention to expand into the vastly successful plant-based milk industry.

Source: Search of the WIPO’s Global Brand Database Search System at https://branddb.wipo.int/en/advancedsearch for registered trademarks and pending trademark applications filtered for owner: Beyond Meat Inc. and Savage River Inc.

Cultivated, or lab-grown, meat is a much newer entrant to the food technology industry. Notably, this industry is still in the process of obtaining regulatory approval around the world. Upside Foods is one of the earliest entrants to the cultivated meat market and the first cultivated food company to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, which was granted in November 2022.6 According to the WIPO’s Global Brand Database, Upside currently has 41 registered trademarks and 16 pending applications. The top three countries to which it has designated its trademark applications for national entry are Mexico, the United States, and Brazil. Upside only started to file for trademark registrations recently, starting in 2021. As the cultivated meat market expands, it will be interesting to see where Upside Foods and other cultivated meat and seafood companies choose to file trademarks.

Conclusion

With more and more entrants into the food technology industry, food technology companies should carefully consider their intellectual property options and how to best protect their critical assets using different types of intellectual property. The recent Impossible Foods and Meati patent and trade secret disputes underscore the importance of selecting the best type of intellectual property to protect critical assets in this fast-growing and competitive market. Therefore, as companies develop food for the future, they should also consider how they can protect their brand and innovations against market competitors.

1 Complaint at 7-11, Impossible Foods Inc. v. Motif FoodWorks Inc., No. 1-22-cv-00311 (D. Del. Mar. 9, 2022), ECF No. 1.

2 Memorandum Opinion and Order, Impossible Foods Inc. v. Motif FoodWorks Inc., No. 1-22-cv-00311 (D. Del. Mar. 9, 2022), ECF No. 31.

3 Emergy Inc. v. The Better Meat Co., 2022 WL 7101973 (E.D. Cal. Oct. 12, 2022), and Better Meat Co. v. Emergy, Inc., 2023 WL 4358122 (E.D. Cal. June 27, 2023).

4 Order, Better Meat Company v. Emergy, Inc. et al., No. 2-21-cv-02338 (E. Cal. Dec. 17, 2021) ECF No. 153, and Order, Emergy, Inc. v. Better Meat Company et al., No. 2-21-cv-02417 (E. Cal. Dec. 27, 2021) ECF No. 42.

5 Beyond Meat. 2019. “Beyond Meat Goes Public!” https://www.beyondmeat.com/en-US/whats-new/beyond-meat-goes-public.

6 Upside Foods. https://upsidefoods.com/company.

This article was originally published on December 15, 2023 for the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) Food Technology Magazine as a Digital Exclusive. The article can be found on the IFT website at this link: https://www.ift.org/news-and-publications/food-technology-magazine/issues/2023/december/columns/mastering-the-recipe-of-food-technology-intellectual-property.