Newsletter sections:

For earlier Anchovy News publications, please visit our Domain Names practice page. Learn more about Anchovy® - Global Domain Name and Internet Governance here.

Domain name industry news

Third phase of .TR launch

The Turkish domain name Registry recently started opening registrations directly under the Top Level Domain (TLD) .TR. The launch follows a specific schedule in order to allow registrants of existing Turkish domain names to secure their matching .TR domain names. The third phase just started and will last for three months.

Up until recently, the Registry only allowed the registration of domain names at the second level under extensions such as .COM.TR, .GEN.TR or .INFO.TR. Like other Registries, such as Australia (.AU) most recently, it is now allowing registrations directly at the top level.

A Grandfathering period divided into three categories started in September 2023. First, applicants falling into Category 1 (that is to say owners of existing domain names registered under .GOV.TR, .EDU.TR, TSK.TR, BEL.TR, POL.TR and K12.TR, which are the extensions for the government, education, police, etc) could secure their matching domain names under .TR. Then in November 2023, it was the turn of applicants falling into Category 2 – namely owners of existing .ORG.TR domain names (that is to say public institutions, public benefit associations, tax-exempt foundations, employee or employer professional organisations) that were registered before 25 August 2023.

Category 3 applications opened on 14 February 2024 and will last until 14 May 2024. This concerns owners of existing domain names under all of the other Turkish extensions, as well as owners of .ORG.TR domain names registered after 25 August 2023. During this period, where multiple applicants apply for the same .TR domain name, priority will be given to the owners of the corresponding second-level domains in the following order: .KEP.TR, .AV.TR, .DR.TR, .COM.TR, .ORG.TR, .NET.TR, .GEN.TR, .WEB.TR, .NAME.TR, .INFO.TR, .BBS.TR, .TEL.TR. Thus for example, if the registrants of anchovy.com.tr and anchovy.gen.tr both apply for the domain name anchovy.tr, priority will be given to the registrant of the .COM.TR domain name.

After the Grandfathering period is over, General Availability is expected to start in June 2024. Anyone will then be able to register their desired .TR domain names on a first-come, first-served basis.

For more information on the launch of .TR, please contact David Taylor or Jane Seager.

Back to the top.

CENTR sets out key principles to “safeguard Europe’s digital future”

CENTR, an association of European country code Top-Level Domain (ccTLD) Registries that includes .DE (Germany), .BE (Belgium) and .IT (Italy), recently launched its initiative: Towards a Stronger Internet: Principles for the Next Digital Decade (the “Initiative”). The principles set out in the Initiative are intended to provide a framework for maintaining “the core elements of the free and open internet” throughout the next five-year EU legislative term and beyond.

CENTR has launched the Initiative in the context of the upcoming European Parliament elections to be held in June 2024 and in anticipation of the advent of Web 4.0 (or “Next Generation Internet”), which will see that “advanced artificial and ambient intelligence, the internet of things, trusted blockchain transactions, virtual worlds and XR capabilities, digital and real objects and environments are fully integrated and communicate with each other, enabling truly intuitive, immersive experiences, seamlessly blending the physical and digital worlds”.

To summarise, the Initiative sets key principles in the following relevant areas:

Interoperability

The Next Generation Internet must continue to be based upon open standards and all stakeholders, notably governments, should support this aim. The EU and its Member States should support and encourage compatibility and interoperability with existing foundational aspects of essential Internet infrastructure by way of mechanisms such as public procurement. On this point, the Initiative affirms that “In order to maintain the internet's openness and ability to evolve further without excluding anyone, interoperability with existing internet infrastructure is a must.”

Competition

On the basis that “diverse, decentralised systems ensure that there is no single point of failure”, EU policymakers should “refrain from harmonising beyond the baseline of open standards: legislation should be technologically neutral to ensure it is future-proof and promotes competition.” In this way “knowledge and power are distributed, not concentrated, increasing consumer welfare and choice.”

Access

Regulatory initiatives should not disproportionately impact the ease of access of European citizens and businesses to digital identifiers such as domain names, as doing so would “push EU citizens to less regulated and less secure environments”.

Cybersecurity

EU policymakers should continue to support collaboration in the area of cybersecurity, working towards the objectives outlined in the Digital Decade Programme 2030, under which:

“…everyone has the skills to use everyday technology. Even small businesses use technology to make better business decisions, interact with their customers or improve parts of their business operations. Connectivity reaches people living in villages, mountains and remote areas, so everyone can reach online opportunities and participate in the benefits of the digital society. Key public services and administrative procedures are online for the convenience of citizens and businesses.”

The Initiative asserts that European ccTLDs have “built up decades of experience in securely managing digital identifiers while safeguarding data protection principles (such as data minimisation) and insisting on respect for human rights (such as due process)” and that European ccTLDs are “available to share that experience”.

Fundamental Rights

This section of the Initiative covers both human rights and privacy and data protection. With regard to human rights, the Initiative states that “EU policymakers should make human rights impact assessments public without exception, to ensure transparency in the face of public scrutiny” and that decision making in the multistakeholder model must be “guided by the tenets of the rule of law, due process, and transparency of decision-making.”

With regard to privacy and data protection, the Initiative states that “Strong data protection safeguards are strictly necessary in a democratic society” and as such, existing data protection standards should be enforced and strengthened. It goes on to observe that:

“Critiques stating that privacy-enhancing and data protection requirements hamper innovation and societally beneficial progress should be met with the already existing legal grounds in the Union’s data protection law, e.g., informed consent to data processing or warrants for law enforcement agencies.”

Online Content

Online content removal at the infrastructure level (e.g. domain name suspension) must be respectful of due process, transparency and involve a competent public authority in order to avoid undesirable outcomes such as human rights breaches and “collateral damage to end-users”.

In this respect, the Initiative asserts that:

“Respect for due process and involvement of public competent authorities when removal of online content is sought, as well as recognition of different levels of intervention at infrastructure level (such as deletion of domain names as a measure of last resort), has resulted in Europe consistently leading the charts of low DNS abuse, and effective consumer protection.”

Finally, it affirms that:

“Studies that accompany impact assessments of proposed legislation targeting removal or blocking of online content should be public without exception.”

Governance

The Initiative states that “the success of the multistakeholder model relies solely on its support from all stakeholders, including governments.” As such, the EU must ensure support for the evolving multistakeholder model by allocating adequate resources and “actively participating in and insisting on its relevance.”

With reference to the Initiative, Polina Malaja, Policy Director at CENTR has commented that:

“CENTR members are committed to making the internet ecosystem stronger, more resilient, and future-proof, and these principles reflect that dedication. As EU heads toward the next digital decade, we must maintain the core elements of the free and open internet that have allowed information society to develop and thrive.

By underlining clear priorities for each area, CENTR puts forward a guiding framework to ensure a safe and human centric digital future.”

The full Initiative: Towards a Stronger Internet: Principles for the Next Digital Decade, can be found here.

For more information, please contact David Taylor or Jane Seager.

Back to the top.

Q4 Domain Name Industry Brief shows continued growth

The Domain Name Industry Brief (DNIB) recently released its report for the fourth quarter of 2023, which shows continued growth across all Top-Level Domains (TLDs).

Q4 2023 closed with 359.8 million domain names across all TLDs, representing an increase of 0.6 million domain names, or 0.2% compared with Q3 2023. Year over year results showed an increase of 8.9 million registered domain names, or 2.5%. Annual registration counts show a rising trend year over year since 2021, as Q4 2022 had closed at 350.4 million domain names and Q4 2021 at 341.7 million.

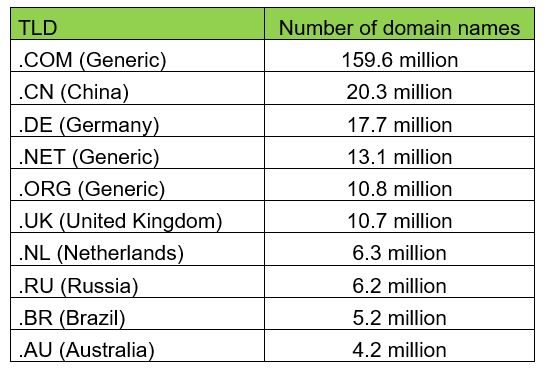

The report shows that the top 10 largest TLDs by number of reported domain names as of 31 December 2023 was as follows:

The fourth quarter closed with 138.3 million domain names across the country code Top Level Domains (ccTLDs), representing an increase of 0.2 million domain names, or 0.2%, compared to the third quarter of 2023. Year over year results showed an increase of 5.3 million registered domain names, or 4.0%. Not surprisingly, yearly registration counts for ccTLDs reflect the same rising trend as mentioned above for all the TLDs.

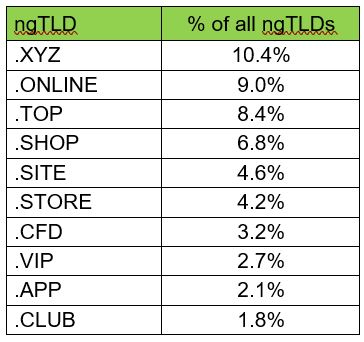

The total number of domain names under the new generic Top Level Domains (ngTLDs) was 31.8 million at the end of Q4 2023, representing an increase of 1.6 million domain names, or 5.3% compared with Q3 2023. Year over year results showed an increase of 4.4 million domain names, or 15.9%.

The top 10 ngTLDs represented 53.2% of all ngTLD domain names, as per the following breakdown:

For more information on the registration of domain names under any TLD, please contact David Taylor or Jane Seager.

Back to the top.

Stable growth for .NL in 2023

SIDN (Stichting Internet Domeinregistratie Nederland), the Registry responsible for running the .NL country code Top Level Domain (ccTLD) for the Netherlands, recently published information concerning the growth of its ccTLD during 2023.

According to SIDN, at the end of 2023 there were 6.3 million registered .NL domain names, which was similar to the number of domain names at the end of 2022. This number peaked in the middle of 2023 at 6.5 million, but it was followed by a decrease due to a combination of factors, such as the non-renewal of domain names (for various reasons such as lack of use, price increase, or simply by inadvertence) and the cancellation of malicious domain names.

SIDN was not surprised by this trend as there was, perhaps inevitably, a downturn in market growth after the unanticipated rapid expansion during the COVID pandemic years. Nonetheless, the high rate of registrations off-set the cancellations and so there was no major reduction of .NL registered domain names. In 2023 there were 915,000 new .NL domain name registrations, which was 10% higher than in 2022 (828,000).

Interestingly, SIDN cites the "disappointing summer weather" as a key reason for the growth. According to them, during periods of good weather, people spend less time indoors at their computers, which often results in a downturn in registrations. Summer 2023 was “abnormally wet" and registrations in August 2023 increased by 34% compared with August 2022. Moreover, more domain names were registered in the summer than in the winter, which runs contrary to the usual pattern.

Overall, there was very little change in terms of the market share for .NL domain names and SIDN believes that .NL, and the domain name industry in general, will experience another year of stability in 2024.

To visit the SIDN website, please click here.

For more information on the registration or recuperation of domain names under .NL, please contact David Taylor or Jane Seager.

Back to the top.

Domain name recuperation news

Unauthorised domain name registration does not necessarily equal bad faith registration

In a recent decision under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) before the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a Panel denied a UDRP Complaint for the disputed Domain Name century21norte.com. The Panel found that the dispute, which arose after the termination of a franchise agreement, did not fall within the scope of cybersquatting or a "similar mischief" that the UDRP was designed to resolve.

The Complainant, Century 21 Real Estate, LLC, was a US company that franchised real estate services in numerous countries worldwide under the brand and trade mark CENTURY 21. The Complainant owned various trade mark registrations for CENTURY 21 dating from April 1977, including in the United States.

It was not disputed that an entity controlled by, inter alia, the Respondent was previously an authorised franchisee of the Complainant. According to the Complainant and documents exhibited by the Complainant, the relevant franchise commenced on 22 May 2007 and terminated on 31 May 2012.

The disputed Domain Name was registered on 15 November 2006. The decision does not provide any details as to the pointing of the Domain Name other than the fact that the Complainant asserted that at the time of filing the Complaint, the Respondent used the Domain Name to divert Internet users from the Complainant's website to its own by misrepresenting a continuing connection with the Complainant.

To be successful in a complaint under the UDRP, a complainant must satisfy the following three requirements:

- The domain name registered by the respondent is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant has rights; and

- The respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name; and

- The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

The Complainant argued that the Domain Name contained, and was therefore confusingly similar to, its CENTURY 21 trade mark. The Complainant also submitted that the Respondent had no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the Domain Name and was not authorised by the franchise agreement to register any domain name comprising its CENTURY 21 trade mark.

The Respondent did not submit a formal Response, but stated informally that it previously had a relationship with the Complainant's CENTURY 21 brand but was in the process of rebranding to stop using it. However, it would like to retain its personal email accounts associated with the Domain Name.

In relation to the first element of the UDRP, the Panel was satisfied that the Complainant had established registered trade mark rights in respect of the mark CENTURY 21 and that the Domain Name was confusingly similar to the Complainant's trade mark.

In relation to the second element of the UDRP, the Panel indicated that the Complainant had established a "good arguable case" that the Respondent had no subsisting rights or legitimate interests in respect of the Domain Name. However, in light of the Panel's findings as to the third element of the UDRP, the Panel declined to reach a firm conclusion in relation to this element of the UDRP.

On the evidence provided, the Panel was not satisfied that the Domain Name had been registered in bad faith. The Panel noted that the Respondent registered the Domain Name some months before its appointment as franchisee of the Complainant, being apparently entitled in that capacity to use the Complainant's CENTURY 21 trade mark in commerce. Although the Complainant contended that the Respondent was not authorised under the relevant franchise agreement to register the Domain Name, the Panel was not satisfied that the Complainant had provided clear evidence that such registration was expressly prohibited.

The Panel further noted that, even if the registration of the Domain Name was unauthorised, as the Complainant argued, that would not automatically constitute registration in bad faith. To make a finding of bad faith registration, the Panel would need to be satisfied that when registering the Domain Name, the Respondent intended to divert business away from the Complainant or its authorised franchisees, or otherwise to take unfair advantage of the Complainant's goodwill in the CENTURY 21 trade mark. The Panel had seen no evidence to that effect and suggested that in the circumstances it would be reasonable to infer that the Respondent registered the Domain Name with a view to becoming a franchisee of the Complainant.

Among the exhibits provided by the Complainant was a money judgment obtained by the Complainant against the Respondent in the Dominican Republic in July 2014, as well as letters from the Complainant to the Respondent, including the following:

Letter dated June 2016 in which the Complainant offered the Respondent settlement terms under which it could obtain a new franchise agreement. Such terms included the immediate transfer to the Complainant or its assignees of "your website century21norte.com and any other website that uses the name Century 21 as any part of the url".

Letter dated July 2016 in which, after "many" failed attempts to reach agreement with the Respondent, the Complainant informed the Respondent that it hereby denied the Respondent and its business the right to use the brand CENTURY 21.

The Panel found that the correspondence exhibited by the Complainant showed that it was aware of the Respondent's use of the Domain Name and indeed that the Complainant had liaised with the Respondent for several years using an email address linked to the Domain Name, before seeking the transfer of the Domain Name as part of a commercial arrangement in June 2016. As a result, the Panel found that there was nothing to suggest that the Respondent had registered the Domain Name improperly and so the Complainant had failed to establish registration in bad faith.

Given that bad faith registration and bad faith use are conjunctive requirements under the UDRP, the Panel declined to consider bad faith use.

The Panel denied the Complaint and found that this case did not fall within the scope of cybersquatting or similar mischief that the UDRP was designed to resolve. Rather, the Panel noted that this case may be better suited to a contractual claim in a national court.

Comment

This decision underlines that a UDRP panel is not a general domain name court and that the UDRP is narrowly crafted to apply to a particular type of abusive registration arising from cybersquatting. This decision also makes it clear that, even if a complainant were to adduce evidence that a disputed domain name had been registered in breach of a commercial agreement, that alone would not necessarily be sufficient to constitute bad faith registration. When it comes to bad faith registration, evidence of a respondent's intention to take unfair advantage of a complainant or of the goodwill in its trade mark is also required.

The decision is available here.

Back to the top.

Running out of evidence of bad faith under .IO Policy

In a recent decision under the .IO Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (.IO Policy) before the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a Panel refused to transfer the disputed domain name courir.io, finding that the Complainant had failed to prove that the Domain Name had been registered or used in bad faith. While .IO is in fact the country code for the British Indian Ocean Territory, it can also be read as an abbreviation for input/output in computer science, and this has made its use significantly more popular in recent years, especially by tech companies.

The Complainant was Groupe Courir, a French retail company selling sneakers, ready-to-wear clothesh and fashion accessories for men, women and children. In 2018 it had 188 stores and 50 affiliated stores in France, as well as 27 stores in Spain, Poland, the Maghreb, the Middle East and overseas territories. The Complainant owned various registered trade marks in COURIR and its main website was linked to the domain name courir.com, registered in 1998.

The Respondent was an individual located in Belgium. In November 2023, he registered the Domain Name courir.io, which resolved to a parking page with commercial "click through" links.

The Complainant initiated proceedings under the .IO Policy for a transfer of ownership of the Domain Name.

To be successful under the .IO Policy, a Complainant must satisfy the requirements of paragraph 4(a) of the .IO Policy, namely that:

(i) the disputed domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trade mark or service mark in which the complainant has rights;

(ii) the respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name; and

(iii) the disputed domain name was registered or is being used in bad faith.

Under the first element of paragraph 4(a) of the .IO Policy, the Complainant indicated that the Domain Name was identical to the COURIR trade mark. The Panel confirmed that the Domain Name was identical to the trade mark, irrespective of the fact that the country code Top-Level Domain (.IO in this case) also appeared.

With regard to the second element of paragraph 4(a) of the .IO Policy, the Complainant claimed that the Respondent had no rights or legitimate interests in the term "courir".

The Respondent answered that "courir" was a French verb meaning "to run" and that the Complainant was attempting to hijack a dictionary word. In addition, he argued that he was an elite track and field athlete who had started running more than 40 years ago. He explained that he was a former 1500m champion and a member of "CABW" which was one of the top Belgian athletics clubs and that he had registered the Domain Name for use in connection with an athletics-related blog which had not yet been created.

The Panel considered that the Complainant had established a prima facie case that the Respondent did not have rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name as the Complainant had not authorised, licensed or permitted the Respondent to register or use the Domain Name. The Panel then stated that the onus was on the Respondent to produce evidence demonstrating rights or legitimate interests. The Panel assessed the evidence of the Respondent's athletic credentials and pointed out that the Respondent had provided limited documentary evidence to support his claim, namely an undated printout of what appeared to be various results in his name regarding a "4x1500" event. The printout seemed to derive from a CABW web address, which upon online search by the Panel, appeared to be the Royal Athletics Club of Walloon Brabant. Further online research led the Panel to conclude that the Respondent was, at least, a competitive amateur athlete who was the record holder at a Belgian club. As a result, the Panel considered that the Respondent's athletics background rendered his argument that he had registered the Domain Name because of its ordinary meaning (i.e. "to run") was at least plausible and credible. However, the Panel noted that the Respondent had done no more than state that he had not had the time to create a hosting account to create the blog/newsletter for which the Domain Name had been registered.

The Panel explained that, as expressed in decisions under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (a similar policy applying to domain names under generic extensions such as .COM), non-exhaustive examples of prior use, or demonstrable preparations to use the Domain Name, in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services could include: (i) evidence of business formation-related due diligence, legal advice or correspondence, (ii) evidence of credible investment in website development or promotional materials such as advertising, letterhead, or business cards (iii) proof of a genuine (i.e., not pretextual) business plan utilising the domain name, and credible signs of pursuit of the business plan, (iv) bona fide registration and use of related domain names, and (v) other evidence generally pointing to a lack of indicia of cybersquatting intent. The Panel specified that, whilst such elements were assessed pragmatically in light of the case circumstances, clear contemporaneous evidence of bona fide pre-complaint preparations was required and that, in the case at hand, the Respondent had produced no contemporaneous evidence corroborating his intent to produce a blog of any kind linked to the Domain Name.

The Panel concluded that it was challenging to determine whether the Respondent had successfully rebutted the Complainant's claim that he had no rights or legitimate interests in the Domain Name. However the Panel noted that it was unnecessary to reach a conclusion on the issue, given the Panel's finding on bad faith.

Under the third element of paragraph 4(a) of the .IO Policy, the Panel held that the Complainant had failed to prove that the Respondent had registered or used the Domain Name in bad faith.

The Complainant argued that the Respondent had linked the Domain Name to a parking page with click through links. It had also been offered for sale on the domain name market place SEDO for USD 3,950. The Respondent indicated that he had mistakenly listed the Domain Name on SEDO for a short period of time but it was not for sale. He also presented SEDO records and stated that he had earned no revenue from the parking of the Domain Name.

In assessing whether the Domain Name had been registered or was being used in bad faith, the Panel noted that (i) the Complainant's evidence comprised a page from the domain name afternic.com (not SEDO) showing the Domain Name offered for sale for USD 3,950, (ii) after checking, the Domain Name was no longer listed for sale on that platform but it still resolved to a parking page, although when the Panel accessed that page from the United Kingdom with a Safari browser, it produced a page with links written in what appeared to be Chinese characters, and the page in question appeared to have been provided by SEDO, and (iii) the Respondent had produced evidence which, on its face, appeared to show that he had earned no revenue from SEDO during the time that the Domain Name had been registered.

The Panel considered that the Respondent had not provided a great deal of information about his intended blog, the nature of the mistake and the reason for the listing on SEDO. However the Panel suggested that the limited evidence could be linked to the Respondent's anger caused by the complaint as he found it hard to believe that his registration of a dictionary word relevant to his background as an athlete could be challenged in such a manner.

Taking the evidence as a whole and on the balance of probabilities, the Panel gave the Respondent the benefit of the doubt and accepted that he was not acting in bad faith and that he had chosen the Domain Name for its dictionary meaning. Amongst other things, the Panel took into consideration the fact the Domain Name was no longer for sale. In addition, the Panel added that it was not clear that any links present on the associated parking page targeted the Complainant or its trade mark.

Accordingly, the Panel was not persuaded that the evidence showed that the Respondent's intent was to target or take advantage of the Complainant or its trade mark, as opposed to registration of the word for its dictionary meaning, given the Respondent's background as an athlete and runner.

As a result, the Panel dismissed the claim for failure to meet the requirements of the third element of paragraph 4(a) of the .IO Policy.

Comment

This case demonstrates that, although the .IO Policy's only requires bad faith registration OR use (as opposed to bad faith registrant AND use under the UDRP), the standard of proof for each alleged bad faith argument under the .IO Policy remains the same and registration or use in bad faith must still be established on the balance of probabilities.

The decision is available here.

Back to the top.

Registration in bad faith is essential for a transfer under the UDRP

In a recent decision under the Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) before the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a Panel denied a UDRP complaint in relation to the disputed domain name garogroup.com. The Panel found that, although the first two elements of the UDRP were satisfied, the Complainant had not provided evidence of bad faith registration of the disputed domain name and so the third element of the UDRP was not satisfied.

The Complainant was a Swedish company that provided goods and services related to electrical installations. It owned the domain names garo.se, registered on 4 September 1996, and garogroup.se, registered on 31 August 2016. No information was available regarding the Respondent.

The disputed domain name was first registered on 18 March 2004 and, over time, previously resolved to several sites with varying content, including offering consulting services in 2008, providing contact information for various philanthropic organizations between 2011 and 2013 and offering college admissions counselling between 2014 and 2015. In January 2016, the disputed domain name stopped resolving to an active website. Between 2020 and 2021, the disputed domain name was offered for sale as a “premium domain name” without a specific price listed. A couple of months prior to filing the Complaint, the Complainant sent a cease and desist letter to the Respondent and received no response. At the time of the filing of the complaint, the disputed domain name was offered for sale for USD 15,000.

To be successful in a complaint under the UDRP, a complainant must satisfy each of the following requirements:

i) The domain name registered by the Respondent is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant has rights; and

ii) The Respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name; and

iii) The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

The Complainant argued that it was the proprietor of numerous trade mark registrations for its GARO mark, including a European Union Trade Mark for GARO, registered on 23 October 2002. In particular, the Complainant argued that it had used the GARO mark since 1939, and had been using the domain name garogroup.se since 2016. The Complainant asserted that it had established all three of the elements required under the UDRP for a transfer of the disputed domain name. The Respondent did not reply to the Complainant’s contentions.

On the first element, the Panel found that the addition of the term “group” did not prevent a finding that the disputed domain name was confusingly similar to the Complainant's GARO trade mark. Therefore the Complainant had satisfied the first element.

With regard to the second element, the Panel emphasised that the Respondent had not rebutted the Complainant's prima facie case that the Respondent lacked rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name, as outlined in the UDRP. As a result, the Panel found that the Complainant had satisfied the second element.

With respect to the third element, the Panel noted that the Complainant's European Union trade mark for GARO, registered in 2002, pre-dated the registration of the disputed domain name in 2004. However, the Panel found that there was no evidence that the GARO mark was a well-known mark and that, on that basis, that the Respondent knew or should have known about it at the time of registration of the disputed domain name. Accordingly, the core issue for the Panel was whether the available evidence permitted any inference that the Respondent was targeting the Complainant's trade mark when it registered the disputed domain name.

The Panel ultimately found that no such inference could be drawn. Although from at least 2008 to 2016 the disputed domain name resolved to a website operated by an entity calling itself the Garo Group, located in California, offering various types of consulting activities, including those related to government services, community organisations and college admissions counselling, as detailed above, the Panel found that there was insufficient evidence that the Respondent targeted the Complainant when registering the disputed domain name. The Panel noted that at the time of registration of the disputed domain name, the Complainant was operating in Sweden and the European market in the field of electrical products and services.

The Panel also considered whether the fact that the "Garo Group" website, to which the disputed domain name previously resolved, was disabled in 2016, the same year that the Complainant registered the domain name garogroup.se, supported an inference that there had been a change of ownership of the domain name. If that were the case, the Panel noted that it could have had a basis for finding that the Respondent targeted the Complainant's trade mark, particularly given that the disputed domain name was subsequently offered for sale at a high price that seemed likely in excess of the Respondent’s costs. However, on the evidence available, the Panel was unable to reach such a conclusion as the Complainant had not provided any evidence that would enable the Panel to infer that the current Respondent was not the original registrant of the disputed domain name. The Panel went on to list the types of evidence that could permit such an inference, including a recent update to the WhoIs record and evidence of recent use that unambiguously targeted the Complainant.

As the Complainant had failed to provide any evidence to support its allegation of bad faith registration, the Panel found that the third element of the UDRP was not satisfied and denied the complaint. Given that the third element of the UDRP is a conjunctive requirement, requiring both bad faith registration and use, the Panel did not need to go on to consider bad faith use. However, the Panel made it clear that the denial was made without prejudice to the Complainant’s right to initiate a new UDRP proceeding in the event that the Complainant was able to provide new information not reasonably available at the time of the filing of the Complaint showing that the Respondent had registered the disputed domain name in bad faith.

Comment

This case illustrates that Complainants should always be mindful of the requirement for both bad faith registration and use under the UDRP. Even if a domain name potentially appears to be being used in bad faith, Panels always need to consider bad faith at the time of registration, even if this was many years ago. It should also be noted that the date on which the Respondent acquired the domain name is the date that a Panel will consider in assessing bad faith registration, and not the date that the domain name was registered for the first time (which is the date that generally appears on the Whois record). In the case at hand, given what appeared on the face of it to be honest conjunctive use by an entity with a similar name a number of years ago, the Panel looked for evidence of a subsequent transfer of the disputed domain name in order to be able to assess bad faith registration at a later date, but found none and so was constrained to deny the case without going on to consider bad faith use.

The decision is available here.

Back to the top.