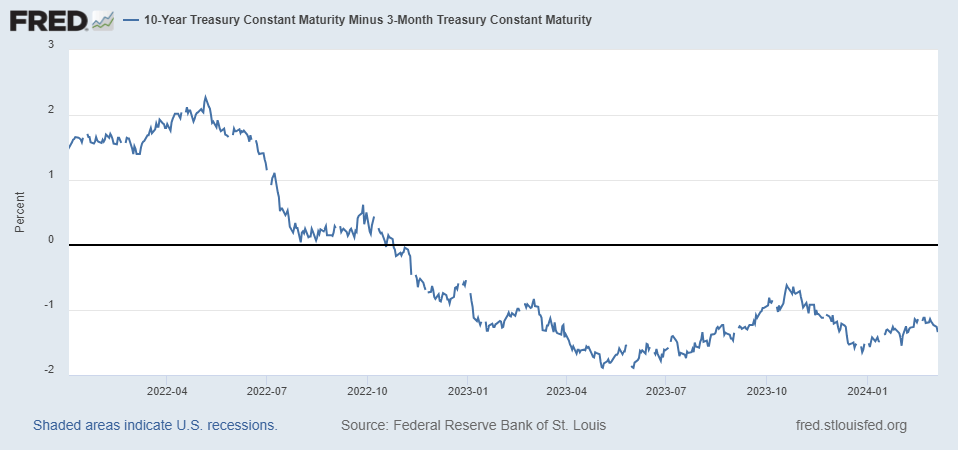

The bond yield curve inverted in October 2022.[1] When that occurred, it started a countdown to recession. At least it has every time since 1968.[2] Specifically, for the last eight recessions since 1968, every single recession was preceded by a bond yield curve inversion.[3]

The last eight recessions include the 2020 COVID-19 recession, the 2007-2009 Great Recession, the 2001 dot-com recession, the 1990-1991 savings & loan crisis recession, the 1981-1982 second double dip recession, the 1980 first double dip recession, the 1973-1975 oil crisis recession, and the 1969-1970 guns and butter recession.[4]

Additionally, since 1968, the bond yield curve inversion has not once given a false signal (an inversion with no following recession).[5] For these reasons, to date, the inversion is the most reliable indicator of a pending recession.

The Inversion Explained

What is the inversion? In short—the interest rates on shorter term U.S. treasuries become higher than the interest rates on longer term U.S. treasuries. Particularly, the primary inversion is when the interest rate on 3-month U.S. Government treasury bills (“T-bills”) becomes higher than the interest rate on 10-year U.S. Government treasury notes.[6]

This inversion of rates is a bizarre occurrence because, generally speaking, a shorter term investment should not have a higher yield than a longer term investment in essentially the same thing.[7] Typically, there is a premium with longer duration.[8] That is, lending out money for a longer time increases the return—because more can be done with the money, and an investor demands a better yield for the prolonged risk and opportunity cost of the longer commitment.[9] The bond yield inversion is a distortion of this general rule.

Arguably, the simplest (but not only) explanation for why the distortion occurs is because bond investor confidence in the economic near term is poor.[10] This increases the demand for the longer term notes—and/or makes investors more willing to accept lower rates on the longer term notes.[11] In turn, this drives down the interest rates that the U.S. Treasury borrower must accept to sell the notes.[12] Conversely, where there is reduced demand for the shorter term T-bills, the U.S. Treasury borrower must accept higher interest rates to sell the T-bills.[13] These conditions can cause the longer term yields to drop below the shorter term yields.[14]

Think of it this way. When bond investors anticipate that the economy is going to falter, they recognize that the Federal Reserve System (“Fed.”) will eventually ease monetary conditions to influence a lowering of interest rates.[15] Therefore, if an investor buys a three-month T-bill, it provides a decent interest rate for the next three months.[16] However, after that interest rates may have dropped, leaving the investor without a favorable opportunity to reinvest.[17] Alternatively, if the investor buys a ten-year note while rates are still elevated, that investor has just locked in a decent yield for the next ten years.[18]

Thus, distrust of the economic near term can increase the demand for the longer term notes, which reduces long term interest rates, and can decrease the demand for the shorter term T-bills, which puts upward pressure on short term interest rates.[19]

Accordingly, the inversion is seen as a serious red flag of investor pessimism. Commence the ominous music.

The Delay

So, if the yield curve inversion is such a dependable indicator of a pending recession, why has a recession not yet occurred? The answer is that there is always a delay. For the last six recessions, the shortest delay between the inversion and the recession was approximately (10) months (the second double dip recession of 1981-1982).[20] The average delay was approximately (14) months.[21] And the longest delay was approximately (23) months (the Great Recession).[22] Plainly, approximately (23) months after October 2022 is on or about September 2024. Therefore, if economic history (at least since the late ‘70s) is a reliable guide, the U.S. is likely to enter a recession by the early fall of 2024. If the delay period runs longer than that, it will set a new benchmark (at least compared to the data since the late ‘70s).

That said, keep in mind that a recession often starts many months before it is officially recognized. In the U.S., the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research (“NBER”) (a Massachusetts non-profit) is generally regarded as the chief umpire for calling a recession.[23] And, as the Government has previously pointed out, “because the committee depends on government statistics that are reported at various lags, it cannot officially designate a recession until after it starts.”[24]

False Signal Possibility

Despite the previous reliability of the yield curve inversion as a recession indicator, could it now be providing a false signal? That possibility cannot be ruled out.

Nonetheless, Professor Campbell Harvey—the Economist who, in his 1986 dissertation, revealed that the inversion is a harbinger—does not believe that the current inversion is a false signal.[25] On February 4, 2024, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York stated that the probability of recession in the next twelve months is at 61.473%.[26] And Economist David Rosenberg—who relies on an economic indicator that he calls the “full model[,]” which supposedly has not given a recession false signal since 1999—puts the chance of a recession in 2024 at 85%.[27] “He noted that in early 2023 this model suggested only a 12% chance of a recession[.]”[28]

Other Indicators

On top of the foregoing, some negative indicators are sprouting.

Arguably, the biggest of which is consumer debt. For consumers, “[c]redit card delinquencies surged more than 50% in 2023 as total consumer debt swelled to $17.5 trillion, the New York Federal Reserve reported Tuesday[, February 6, 2024].”[29] This is consumer debt surging against a backdrop of low unemployment and faster wage growth (discussed below). A significant part of the explanation for the burgeoning consumer debt has to be inflation.

Particularly, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (“PCE”) core inflation rate for January 2024 was 2.8%.[30], [31] That is significantly less than the high water mark of 5.3% in February 2022, but still above the 2% target.[32] Keep in mind that the current inflation run started on or about March 2021, and has its proximate roots in the money supply increasing by approximately 35% over 2020 and 2021—while, because of COVID-19, the supply of available goods and services was decreasing.[33]

Importantly, since the inflation high water marks of 2022, mostly what has occurred is disinflation (decrease of the inflation rate), not actual deflation (price decreases). Therefore, generally speaking, consumers are still living with the higher pricing that started climbing on or about March 2021.

Further, when talking about inflation experienced at the individual consumer level, arguably, the top three things that dominate that experience are food, shelter, and energy (transportation fuel, etc.).[34] And, whereas energy costs have been decreasing (at least according to the January CPI numbers), food and shelter costs are still quite elevated.[35]

So, if consumer spending buoyed the economy in 2023, and will be the primary determinant for whether a recession occurs in 2024 (given that consumption is roughly two-thirds of the economy),[36] it would seem that continued disinflation, and even some deflation, is key—particularly for food and shelter.

Turning to commercial real estate, “[t]he amount of delinquent commercial property debt held by the top banks nearly tripled in 2023 to $9.3 billion, the FT [Financial Times] said. For the overall banking sector, delinquencies on loans backed by offices, malls, apartments, and other commercial properties more than doubled last year to $24.3 billion from $11.2 billion.”[37]

Furthermore, “[t]here were 635 US commercial real estate foreclosures in January [2024], up 17% from the previous month and roughly twice as many as in January 2023, according to a report from Attom.”[38] So, some negative trending there, but not nail-biting levels of delinquencies.

“U.S. bankruptcy filings surged by 18% in 2023 on the back of higher interest rates, tougher lending standards[,] and the continued runoff of pandemic-era backstops,” although the number of 445,186 filings was still below “the 757,816 bankruptcies filed in 2019[.]”[39] Again, negative trending, but not terrible.

In the residential real estate sector, the fourth quarter 2023 seasonally adjusted home mortgage delinquency rate for one-to-four-unit residences was low at 3.88%, which is less than the historical average of 5.25%.[40] However, in December, Fitch reported that “[a]s of 2Q2023, home prices in 88% of the country’s MSAs [metropolitan statistical areas] were overvalued, with 55% of these areas by 10% or more.”[41]

More distressing, as of October 31, 2023, the average cost of a home is now 7.57 times the median household annual income.[42] That is a significant affordability deterioration from December 2019 (before the pandemic), when the average cost was 5.67 times the median household annual income.[43] Moreover, it is higher than the peak of the housing bubble in April 2006, when the average house cost was 6.81 times the median household annual income.[44] Consequently, for residential real estate, a broad downward adjustment is arguably due.

The February 2, 2024 Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) jobs report shows that, for January 2024, the unemployment rate remains low at 3.7%, which, generally speaking, is great.[45]

However, the December 2023 Employment Cost Index (“ECI”) report (released quarterly) shows compensation increasing at a rate of 4.2%—down from 5.5% in the second quarter of 2022, but arguably still inflationary.[46] As part of this, in July 2023, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston reported that wage growth among low-skilled workers has, to date, been a significant driver of supercore inflation (inflation excluding food, shelter, and energy).[47]

Specifically, “[t]he prices of services associated with low-skill workers have been a key driver of ‘supercore’ inflation, which excludes food, energy prices, and shelter prices. Low-skill-services inflation seems to be tied to faster wage growth in those industries coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic. Wage growth in low-skill services has begun to decline, suggesting that there may be lower inflation in these industries going forward. At the same time, wage growth in high-skill services has recently accelerated, suggesting that there may be higher inflation in these industries in the near future.”[48]

So, there appears to be a tension between the low unemployment rate and getting wage growth (as shown by the ECI rate) to slow down to a level that supports the overall target inflation of 2%.

The BLS January 2024 reporting also shows that the average weekly hours for U.S. workers has fallen to 34.1 hours.[49] That’s a full half hour decline from January 2023, and the lowest number since March 2020.[50] The low number could represent a labor mix shift to part-time work, and/or increased under-employment of full-time workers. Either of which might be an indicator of decreasing demand for labor, possibly because of slowing business. Alternatively, the decrease could be more reflective of the expanding gig economy, increased automation, and/or changing attitudes on the work week.

In any event, as Professor Harvey has previously pointed out, “GDP growth tells us about the past. Earnings growth tells us about the past. The unemployment rate is a well-known ‘lagging indicator’ of the business cycle.”[51] NBER data corroborates that low unemployment is a lagging indicator—showing that in the (12) recessions since 1948, (7) commenced while unemployment was less than 5%.[52] Thus, low unemployment is not a reliable gauge of a future recession.

Last, the global economy has a role to play. Specifically, Germany, Japan, and Great Britain are now in recessions.[53] And, among other economic woes, China is experiencing a persistent bout of consumer price deflation that started on or about July 2023.[54] Additionally, at the producer level, Chinese businesses have been experiencing price deflation for approximately a year.[55] Given the inter-connectedness of the global economy, these events will have some degree of negative impact on the U.S. economy.

In sum, the bond yield curve inversion shows the likelihood of a recession this year. Other economic indicators do not provide a compelling basis to disregard the inversion. To be clear, the foregoing does not address whether a pending recession will be severe or mild.

Contractor and Subcontractor Food for Thought

In the context of a recession, there are some basic things that merit discussion.

The WARN Act

First, if a Government contractor or subcontractor is going to conduct a furlough or layoff, that employment interruption (whether temporary or permanent) may be subject to the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (“WARN Act”) of 1988. See 29 U.S.C. §§ 2101-09.

With exceptions, the WARN Act requires any employer with 100 or more employees (by head count or aggregate hours) to provide notice at least 60 days prior to the employment interruption of at least 50 employees if that stoppage is occurring as part of a “plant closing” or “mass layoff”—as those terms are defined under the Act.[56] Hence, 100-60-50 is the general rule.

To be at the 100-employee threshold, the employer must be a “business enterprise that employs—(i) 100 or more employees, excluding part-time employees; or (ii) 100 or more employees, including part-time employees, who in the aggregate work at least 4,000 hours per week, exclusive of hours of overtime.”[57]

A “plant closing” is defined as “[t]he permanent or temporary shutdown of a single site of employment, or one or more facilities or operating units within a single site of employment, if the shutdown results in an employment loss at the single site of employment during any 30-day period for 50 or more employees excluding any part-time employees[.]”[58]

A “mass layoff” means “a reduction in force which– (A) is not the result of a plant closing; and (B) results in an employment loss at the single site of employment during any 30-day period for– (i)(I) at least 33 percent of the employees (excluding any part-time employees); and (II) at least 50 employees (excluding any part-time employees); or (ii) at least 500 employees (excluding any part-time employees)[.]”[59]

If the contemplated employment interruption meets the definition of a plant closing or mass layoff, the employer must provide the sixty-days-prior-notice to each employee and/or employee representative (e.g., a labor union), and to state and local government.[60]

As part of this, an employer cannot piecemeal layoffs/furloughs involving the same site to avoid the requirements of the Act.[61] To this end, the employer is supposed to bundle together employment disruptions occurring within a 90-day period to assess whether the notice requirement is being triggered.[62] That is “unless the employer demonstrates that the employment losses are the result of separate and distinct actions and causes and are not an attempt by the employer to evade the requirements of this chapter.”[63]

Despite the foregoing, there are exceptions to the sixty-day-prior-notice requirement.

Generally speaking, the exceptions include:

(1) the employer has a good faith belief that the sixty-days-prior notice would prevent the employer from obtaining capital or business that could stave off the employment interruption;[64]

(2) the interruption is caused by a not reasonably foreseeable business circumstance;[65]

(3) the interruption is caused by a natural disaster;[66]

(4) it is an employment interruption to temporary employees because of the closing of a temporary facility, or the end of a limited duration project;[67] or

(5) the employment interruption is a strike or lockout.[68]

For the first three exceptions, the employer must still “give as much notice as is practicable[,] and at that time shall give a brief statement of the basis for reducing the notification period.”[69]

The exception for a not-reasonably-foreseeable business circumstance is particularly relevant to a recession. Specifically, U.S. Department of Labor (“DoL”) regulations state that “[a]n important indicator of a business circumstance that is not reasonably foreseeable is that the circumstance is caused by some sudden, dramatic, and unexpected action or condition outside the employer’s control.”[70] For which, an “employer must exercise such commercially reasonable business judgment as would a similarly situated employer in predicting the demands of its particular market. The employer is not required, however, to accurately predict general economic conditions that also may affect demand for its products or services.”[71]

Accordingly, as stated by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, “[a] principal client’s sudden and unexpected termination of a major contract with the employer, a strike at a major supplier of the employer, and an unanticipated and dramatic major economic downturn might each be considered a business circumstance that is not reasonably foreseeable.”[72] Hence, a recession likely qualifies as a not-reasonably-foreseeable business circumstance. Indeed, even if a recession is generally anticipated, likely, it is beyond reasonable business judgment to predict the exact timing, or the scope of the impact on business operations.

It is also worth noting that, for the temporary employee exception, DoL regulations state the following.

“Certain jobs may be related to a specific contract or order. Whether such jobs are temporary depends on whether the contract or order is part of a long-term relationship. For example, an aircraft manufacturer hires workers to produce a standard airplane for the U.S. fleet under a contract with the U.S. Air Force with the expectation that its contract will continue to be renewed during the foreseeable future. The employees of this manufacturer would not be considered temporary.”[73]

Thus, regarding an employee who is hired only for a specific Government contract or subcontract (not to be reassigned to other projects), and the nature of the requirement is something unlikely to recur after the contract/subcontract is complete, that employee is likely a temporary employee for the application of the WARN Act.[74]

Overall, “[t]he purpose of the WARN Act is to protect workers by obligating employers to give their employees advanced notice of plant closings. This allows workers who will be laid off time to ‘adjust to the prospective loss of employment, to seek and obtain alternative jobs and . . . to enter skill training or retraining that will allow [them] to successfully compete in the job market.’ ”[75]

Therefore, the spirit of the law is proactive communication with employees to give them time to mitigate the harm caused by losing work. So, even where there is no notice requirement, the Act still encourages employers to provide to workers as much early warning as is practicable.[76]

DoL provides a WARN Act employer guide, available here.[77] Page 13 of the guide discusses potential penalties for non-compliance.[78]

In addition to the foregoing, some states have their own WARN statutes, which may have more imposing requirements than the Federal WARN Act. And, if any affected employee is covered by a collective bargaining agreement (“CBA”), that CBA may impose its own employer notice requirements (e.g., as part of a layoff clause). The CBA may also impose other requirements on an employer, such as conducting layoffs in the order of least-to-most seniority.

There currently is a bill in Congress that seeks to amend, and substantially increase requirements related to, the WARN Act—H.R. 6358, the Fair Warning Act of 2023.[79] The proposed expansions of the WARN Act include, among other things: (1) expanding the coverage of the Act to any employer who has 50 employees (calculated including part-time employees), or an annual payroll of $2 million; (2) increasing the prior notice requirement to 90 days; and (3) expanding the definition of a “mass layoff” to include the employment interruption of 10 employees at a single site.[80]

More EPA Clause Adjustments

At this point, inflation has been running for almost three years. In response, more fixed-price contracts now have Economic Price Adjustment (“EPA”) clauses.

When present in a fixed-price contract, an EPA clause protects the Government and the contractor from market volatility by establishing price adjustments based on certain changed cost or price inputs. Importantly, unlike the changes clause, which provides relief retrospectively to cover cost changes that already occurred, an EPA clause adjustment is prospective. It merely adjusts the going-forward unit price—often from the date of the adjustment submittal.

The most common EPA clauses are as follows.

- A tailored EPA clause in accordance with FAR 16.203-4, which typically provides an adjustment based on a cost index (or multiple indexes) that the parties choose

- FAR 52.216-2 (Economic Price Adjustment-Standard Supplies), which provides an adjustment based on a change to a contractor’s established pricing

- FAR 52.216-3 (Economic Price Adjustment-Semistandard Supplies), which also provides an adjustment based on a change to a contractor’s established pricing

- FAR 52.216-4 (Economic Price Adjustment-Labor and Material), which provides an adjustment based on a contractor’s actual costs for labor/fringe and materials

- DFARS 252.216-7000 (Economic Price Adjustment—Basic Steel, Aluminum, Brass, Bronze, or Copper Mill Products), which provides an adjustment based on a change to the contractor’s established pricing

- DFARS 252.216-7001 (Economic Price Adjustment—Nonstandard Steel Items), which provides an adjustment based on a change to labor costs and the contractor’s established pricing for steel items

- GSAR 552.216-70 (Economic Price Adjustment—FSS Multiple Award Schedule Contracts), which provides an adjustment based on a change to the contractor’s catalog/pricelist

- GSAR 552.216-71 (Economic Price Adjustment—Special Order Program Contracts), which provides an adjustment based on the Producer Price Index (“PPI”)

- I-FSS-969, which provides an adjustment based on: (1) pre-negotiated escalation rates; (2) an agreed-upon index; or (3) for extraordinary market conditions, a negotiated change

Setting aside the specifics of each clause, generally speaking, an EPA clause cuts both ways. Which is to say, it provides both upward and downward adjustments. That means it gives the Government the benefit of cost deflation. And, during a recession, there is an increased likelihood of deflation. Consequently, an EPA clause, which may have previously provided contract price increases, could start triggering contract price decreases. And to make that possibility even spicier, whereas EPA clauses typically put a ceiling on aggregate upward adjustments (e.g., 10%), there usually is no floor for downward adjustments.[81], [82]

Additionally, despite the heightened chance of EPA clause downward adjustments, a recession does not rule out the possibility of upward adjustments. Indeed, in a recession some businesses fail, or otherwise experience increased difficulty in delivering products and services. This can reduce the pool of available goods and services, and actually cause prices to go up for certain items. Therefore, for some materials and services, a contractor or subcontractor might actually experience stagflation (recession-inflation). Hence, even during a recession, EPA clause upward adjustments may occur.

More information on economic price adjustments is available in my October 10, 2022 note, An In-Depth Examination of Inflation Relief for a Government Contractor.[83]

Increased Risk of Funding Delays, Funding Shortfalls, and Options Not Being Exercised

The growing Federal debt burden will be aggravated by a recession. Either because of depressed tax revenues, stimulative Government spending, or both. This is likely to generate significant pressure for the Federal Government to reduce discretionary spending. In turn, any reconciliation of the expanding deficit will increase the risk of contract funding delays, funding shortfalls, and options not being exercised.

According to usdebtclock.org, the U.S. presently has a total system debt (Federal, state, local, financial institutions, businesses, and households) that is approximately three-and-a-half times (350%) the U.S. gross domestic product (“GDP”).[84], [85] Basically, a debt burden of $97.7 trillion over a GDP of $27.9 trillion.[86] By comparison, China’s total debt is somewhere north of 280% of its GDP.[87]

Focusing on the U.S. Federal Government, its debt currently sits at $34.4 trillion and climbing—a figure that is 123% of the U.S. GDP.[88] Stated another way, at current interest rates, the Government is adding approximately $1 trillion to the national debt every 100 days.[89]

The Government’s recent debt accumulation is mountainous. Particularly, the U.S. Government over-spent by approximately $3.13 trillion in FY2020, $2.77 trillion in FY2021, $1.38 trillion in FY2022, and at least $1.7 trillion in FY2023.[90]

Compare the above figures to the cost of WWII.[91] The inflation-adjusted cost of WWII was approximately $4.72 trillion in 2020 dollars, or approximately $5.62 trillion in 2024 dollars.[92] Thus, since 2020, the Government deficit spent ~1.6 to 1.9 times the inflation-adjusted cost of WWII (albeit not at the same proportions of GDP). In turn, to support the deficit spending, the U.S. Treasury has had to sell in the bond market more and more debt (T-bills, notes, bonds, etc.)—both to issue new debt, and to fund the retirement and/or rollover of old debt.

Turning to revenue, according to the Federal Reserve Economic Data (“FRED”), since 1929, the Federal Government has never pulled in more revenue than ~20% of GDP (the “Hauser line”).[93] For 2022, Federal receipts were 19% of GDP.[94] That is almost to the Hauser line, and hence could be considered close to tax optimality.

Yet, for 2023, the current data shows that receipts slipped to 16.2%—a significant decrease.[95] Based on the GDP figure of $27.9 trillion, those receipts (3.8% shy of ~20%) were ~$948.6 billion below the Hauser line. So, applied to the Federal Government’s current spending habits, even if the Federal Government obtained that ~$948.6 billion, it would only have offset the deficit spending for approximately 100 days.

Now, layer on top of the foregoing a recession. “Typically, receipts crash following recessions because, as people’s incomes fall, they owe less to the Treasury.”[96] For example, because of the 2007-2009 Great Recession, Federal receipts dropped from 17.74% of GDP to 14.37%.[97] Therefore, a recession will widen the gulf between the Government’s receipts and liabilities, putting additional pressure on the U.S. Treasury to sell more debt. And this is before contemplating whether Congress will conduct any expensive economic stimulus and/or bailouts—as Congress did for the Great Recession and COVID-19.

Accordingly, a recession will escalate two problems.

First, interest payments on the accumulating debt will accelerate, gobbling up more and more of the Federal budget. The current Congressional Budget Office (“CBO”) outlook shows, for FY2024, interest on the national debt is budgeted at $870 billion, and defense spending at $822 billion.[98] So, even without a recession, this fiscal year, the cost of servicing the national debt will surpass defense spending.

Further, the interest payments are also higher than the FY2024 budget for medicaid, the children’s health insurance program (“CHIP”), and health insurance subsidies ($678 billion).[99]

In fact, the interest cost is only less than the cost of two programs—social security ($1.4 trillion), and medicare ($896 billion).[100]

Nonetheless, as budget-oppressive as the interest cost is now, layer on a recession, the interest payments will balloon. And, likely, those payments will quickly surpass medicare, and start moving toward displacing social security as the number one Federal program.

The second problem is that the growing debt hampers any move by the Fed. to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates.[101] Simply, to fund deficits, the Treasury needs to attract bond investors. And, if bond investors will only purchase Government debt at elevated interest rates, that will influence the interest rates across the wider economy—working against any moves that the Fed. makes to try to lower interest rates.[102]

For these reasons, a recession twists the proverbial knife on a high Federal debt burden.

Raising taxes will not fix these problems. Raising taxes during a recession would hinder economic recovery. And, even if Congress did it, the Government could only collect so much before receipts hit the Hauser line (which would be based on a contracted GDP).

In sum, sooner or later, one way or the other, significant budget cuts will be on the table. A recession likely hastens that day.

Discretionary vs. Mandatory Spending

Moreover, when that day comes, discretionary spending is the likely loser.

Recall, Government spending is generally categorized as two types: direct/mandatory (“budget authority provided by law other than appropriation Acts; (B) entitlement authority; and (C) the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program”); and discretionary (“budgetary resources (except to fund direct-spending programs) provided in appropriation Acts.”).[103]

Since, generally speaking, discretionary spending requires recurring appropriation acts, and mandatory spending does not, it is easier for Congress to cut discretionary spending.

Currently, mandatory spending (excluding interest payments) is 60% of the total budget, and in that bucket is social security and medicare (together 36% of the total budget).[104] Furthermore, based on public polling from approximately a year ago, “79% say they oppose reducing the size of Social Security benefits and 67% are against raising monthly premiums for Medicare.”[105] Hence, mandatory spending is also more difficult to cut because it includes entitlement programs like social security and medicare that most Americans are resistant to curtailing.

The Federal Government’s procurement spend in FY2023 was $765 billion ($470 billion for defense agencies),[106] and most of the procurement spend was discretionary spending. So, given that discretionary spending is more likely to be cut than mandatory spending, procurement spending cuts will be part of any significant budget cuts.

Thus, because a recession is likely to trigger discretionary spending cuts, a recession increases the risk of contract funding delays, funding shortfalls, and options not being exercised.

Working at Risk

With the preceding in mind, it is important to note that if a contractor proceeds with contract work knowing that the Government program does not have funding, that contractor risks working for free.

Specifically, “[i]t is well established that the government is not bound by the acts of its agents beyond the scope of their actual authority.”[107] “[E]ven if a government employee purports to have authority to bind the government, the government will not be bound unless the employee actually has that authority.”[108] As part of this, the Anti-Deficiency Act makes clear that a Contracting Officer only has authority for a contract action if there is, available for obligation, correct appropriated funding.[109]

Granted, a contractor is not required to be knowledgeable about fiscal law, the appropriation, apportionment, and allotment processes, or the drawdown of an appropriation upon which a procurement is premised. All the same, a contractor is not permitted to be completely oblivious, or act contrary to knowing better. As the Supreme Court stated in Salazar, “Contractors are responsible for knowing the size of the pie, not how the agency elects to slice it.”[110]

What this means in practice is, if there is a valid and adequate appropriation at the time a contract/order is issued, a modification is made, or an option is exercised, what fiscally happens to the Government during the corresponding performance period is the Government’s problem—not the contractor’s. The contractor will be protected by the Ferris-Dougherty rule, and will still get paid—even if use of the 31 U.S.C. § 1304 judgment fund becomes necessary.[111]

Additionally, even if there is not a valid and adequate appropriation at the time of the contract action, as long as the contractor does not know it, and there is not sufficient reason for the contractor to know it, likely, the contractor is still protected.[112]

However, the Government may get free work if, at the time of the at-issue contract action, the contractor has actual knowledge that there is not a valid and adequate appropriation, or should know because it is publicly known that Congress did not appropriate sufficient funding.[113] This latter situation can arise if a procurement/program is earmarked in an appropriation bill—making it unambiguous the exact funding available for the procurement. If a contractor proceeds despite that it knew or should have known better, similar to the contractor in Sutton, compensation may be limited to what, if anything, was actually appropriated.[114]

The foregoing principles are behind contract clauses for the availability of funds, limitation of funds, and limitation of the Government’s obligation.[115] Hence, for example, in FAR 52.232-18 (Availability of Funds), it states that “[n]o legal liability on the part of the Government for any payment may arise until funds are made available to the Contracting Officer for this contract and until the Contractor receives notice of such availability, to be confirmed in writing by the Contracting Officer.”[116]

In short, the word to the wise is if there is not funding for a contract action, a contractor should be wary of performing it.

Improper Option Exercise

Last, delayed funding increases the chances that a Contracting Officer will not timely exercise an option.

“An option is an offer couched in specific terms, the acceptance of which must be unconditional and in exact accord with the terms offered. . . . Even substantial compliance with the terms of an option is insufficient.”[117]

So, if the Contracting Officer makes an untimely attempt to exercise an option, it is invalid.[118] And the contractor does not have to accept it. But see Alliant Techsys., Inc. v. United States, 178 F.3d 1260, 1227 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (where the Government improperly exercised an option, and the option exercise did not constitute a material breach, the ensuing disagreement between the Government and the contractor obligated the contractor to continue performing under the disputes clause).

Nonetheless, assuming that the contractor still wants to perform the work, the contractor is entitled to an equitable adjustment on the improperly exercised option.[119] Thus, it is prudent for the contractor to immediately inform the Contracting Officer that the improper exercise of the option is not excused, and that the contractor will seek an upward adjustment for performing the option.

Getting Reimbursed for Delays and Disruptions

In an economic downturn, generally speaking, there is an increased risk of less work. In turn, if a business does not have enough activity to adequately absorb interruptions and inefficiencies, each delay or disruption to starting or continuing contract performance can hurt more. So, when the Government hinders performance, or causes a work stoppage, it may be of heightened importance to recover the additional costs stemming from a Government-caused delay/disruption.

Although the terms “delay” and “disruption” are sometimes used interchangeably, technically, a “delay” request seeks the costs of a work stoppage, and a “disruption” or “impact” request seeks the costs associated with work becoming more expensive, difficult, and/or less efficient.[120]

A delay/disruption may be ordered by the Government (e.g., a stop work order),[121] or occur constructively from Government action, inaction, or error/omission.[122] A delay/disruption may impact all, or only part, of a contract. And a “[d]elay/disruption can cause the contractor to slow down or stop work, or perform work in an uneconomical manner.”[123]

Monetary relief for a Government-caused delay/disruption may be available under a delay clause,[124] or alternatively under the changes clause.[125] Also, there may be other contract clauses which, circumstance dependent, provide relief for a Government-caused delay/disruption.[126] Nonetheless, a delay or changes clause is the main place to seek a remedy.

Generally speaking, possible cost elements of recovery include, but are certainly not limited to, the following.

- Precontract Costs. These are the costs of ramping-up prior to contract formation when it is necessary to do so to meet the performance schedule.[127] This issue can arise where there is a delay in the contracting process.

- Idle or Inefficient Labor. These are the costs of labor being fully or partially idle, or experiencing degraded efficiency.[128] A contractor’s decision not to re-task or furlough an idle or inefficient worker must be reasonable in order to recover costs.[129] Yet, retention fears can provide a reasonable basis for not re-assigning or furloughing a worker.[130]

- Idle Facilities. An idle facility is a “completely unused” facility.[131] The cost of an idle facility is recoverable if the facility is “necessary to meet fluctuations in workload[,]” or was “necessary when acquired and [is] now idle because of changes in requirements, production economies, reorganization, termination, or other causes which could not have been reasonably foreseen.”[132] The cost is comprised of “maintenance, repair, housing, rent, and other related costs; e.g., property taxes, insurance, and depreciation.”[133]

- Underutilized Facilities (a.k.a. Idle Capacity). Idle capacity “means the unused capacity of partially used facilities. It is the difference between that which a facility could achieve under 100 percent operating time on a one-shift basis, less operating interruptions resulting from time lost for repairs, setups, unsatisfactory materials, and other normal delays, and the extent to which the facility was actually used to meet demands during the accounting period.”[134]

- Idle or Underutilized Equipment. Under FAR 31.205-17, “Facilities means . . . equipment, individually or collectively, or any other tangible capital asset, wherever located, and whether owned or leased by the contractor.”[135] Hence, generally, the cost recovery for idle or underutilized equipment follows the principles behind an idle facility and idle capacity.[136]

- Indirect Costs on Top of Direct Costs Incurred. “Indirect costs allocable to direct costs incurred as a result of the delay are allowable when computed in accordance with the contractor’s established accounting practices [ ].”[137] However, “[a]ny indirect cost (including unabsorbed overhead) submitted as [a] direct cost must be excluded from the computation of rates allocable to the delay/suspension REA or claim.”[138]

- Unabsorbed Home Office Overhead (“HOOH”) Costs (a.k.a. Eichleay damages). “Home office overhead costs are those costs that are expended for the benefit of the whole business and cannot be attributed to any particular contract.”[139] Usually, home office overhead/G&A costs are calculated by applying the applicable indirect rate to the underlying indirect and direct costs. However, where a delay/disruption causes contract direct costs to significantly decrease (if not cease entirely), the business is still incurring the HOOH cost, but a fair allocation of that cost is no longer being supported (absorbed) by the at-issue contract. Thus, “[t]he Eichleay formula provides a method of constructively calculating daily extended home office overhead, using contract billings, total billings for the contract period, total overhead, days of contract performance, and days of delay.”[140]

- Reasonable Profit on Costs Incurred. Recovery of a reasonable profit on delay/disruption-caused costs may be possible, but it depends on the contract clause used to seek recovery.[141]

Notwithstanding the foregoing, it is important to remember that, in a situation of Government caused delay/disruption, the contractor still has a duty, to a reasonable extent, to mitigate damages.[142] Failure to do so could make some costs unrecoverable.

Further, depending on the contract clause being relied upon, a contractor should pay attention to the time period for any advanced notice due to the Contracting Officer. See, e.g., FAR 52.243-2(c) (Changes-Cost-Reimbursement) (“The Contractor must assert its right to an adjustment under this clause within 30 days[.]”). To be clear, the advanced notice is not the actual submission of a request for equitable adjustment (“REA”).

Furthermore, a delay/disruption period may be followed by a work acceleration to make up for the delay/disruption. Accordingly, a delay/disruption REA is often accompanied by a changes clause acceleration REA to recover the increased costs of the work acceleration. Which could include overtime costs, or otherwise more expensive labor or materials—perhaps because those things are being obtained on an expedited basis.

Additionally, generally, the reasonable costs of preparing, submitting, and negotiating an REA are contract administration costs, and consequently are also recoverable.[143] So, it is common to include those costs in an REA, or in a follow-on mini-REA.

Finally—and this may be the most important point of all—delay/disruption costs are substantiated with record-keeping. Ideally, copious record-keeping. That means daily detailed attention to timesheets, payroll records, utilization reports, and other records that will capture the particulars as to how the delay/disruption impacts the contractor. The better the record-keeping, the easier it is to make the case for the REA.

Therefore, with the above-mentioned in mind, in a recession, a contractor may be able to mitigate the economic pain of a Government-caused delay or disruption.

Bankruptcy Protection from a Procuring Agency

If a contractor files a bankruptcy petition—whether under Chapter 7 (liquidation), Chapter 11 (reorganization), etc.—the U.S. Bankruptcy Code automatically imposes a statutory stay that prevents collection actions and judgments against the contractor. See 11 U.S.C. § 362; Santa Fe Builders, Inc., ASBCA No. 52021, 00-2 BCA ¶ 30,983 (June 16, 2000) (“The automatic stay provisions of the Bankruptcy Code, 11 U.S.C. § 362, become[s] effective the moment a bankruptcy petition is filed.”).

Specifically—

“[A] petition filed under section 301, 302, or 303 of this title . . . operates as a stay, applicable to all entities, of– (1) the commencement or continuation, including the issuance or employment of process, of a judicial, administrative, or other action or proceeding against the debtor that was or could have been commenced before the commencement of the case under this title, or to recover a claim against the debtor that arose before the commencement of the case under this title[.]”

11 U.S.C. § 362(a).

“The Stay was enacted to: (1) preserve the status quo for the benefit of the Debtor, the bankruptcy estate[,] and the creditors of the estate; (2) prevent any actions against the Debtor’s property or property of the estate; (3) prevent the continuing harassment of the Debtor; and (4) prevent actions by creditors that would negatively impact on the Bankruptcy Code’s policy of equality of distribution.”[144]

Thus, the stay provision applies broadly, holding at bay a broad swath of creditors and other parties that would otherwise take action against the bankruptcy petitioner. Unless lifted by the bankruptcy court, generally, the stay remains in effect until the bankruptcy case is dismissed or closed. See 11 U.S.C. § 362(c)(2).

What this means for a government contractor is that the stay acts as a bar to some things that the Government might do in its procurement capacity (as a marketplace participant).[145] Yet, generally speaking, the stay does not withhold the Government’s police or regulatory powers.[146]

Consequently, once a contractor files a bankruptcy petition, an agency (in its procurement capacity) is statutorily barred from taking many adverse administrative actions against the contractor.[147] For example, without permission from the bankruptcy court, generally, a procuring agency cannot default terminate the contractor,[148] issue a debt determination against the contractor,[149] or conduct an offset/recoupment against the contractor.[150]

Whether it is permissible for the agency to suspend or debar the contractor will likely depend on the basis of the proposed suspension/debarment. Specifically, whereas the bankruptcy stay may protect the contractor from a suspension/debarment merely based on contract non-performance, or the fact that the contractor filed for bankruptcy, the stay probably will not prevent a suspension/debarment that is pursuant to a police or regulatory function.[151]

Given the contractor-favorable aspects of the bankruptcy stay, a contractor may use the stay to obtain sufficient time to resolve its financial difficulties, and resume contract performance with bolstered tenacity. Alternatively, it can give the contractor an opportunity to negotiate a termination-for-convenience or no-cost termination.

Summation

To reiterate, the bond yield curve inversion shows the likelihood of a recession this year. Other economic indicators do not provide a compelling basis to disregard the inversion. Whether any recession will be severe or mild, go fish.

A recession will aggravate the Government’s already precarious levels of over-spending. This heightens the risk of discretionary spending cuts.

Also, as discussed, a recession stirs up other potential issues for Government contractors and subcontractors.

If you made it this far, thanks for going the distance and reading the whole note.

[1] See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, Fed. Res. Economic Data (“FRED”), 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Minus 3-Month Treasury Constant Maturity (T10Y3M), fred.stlouisfed.org (as of Feb. 22, 2024), available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T10Y3M/.

[2] See Phil Rosen, The inventor of the market’s most famous recession indicator is confident the inverted yield curve is accurately calling a slowdown in 2024, businessinsider.com (Jan. 20, 2024), available at https://www.businessinsider.com/recession-outlook-economy-inverted-yield-curve-inventor-financial-markets-investors-2024-1 (“Dating back to 1968, the indicator’s predictive power is eight for eight, with zero false signals. [Economist Campbell] Harvey told host Jack Farley on the Forward Guidance podcast Thursday that given that yields inverted in the fall of 2022, this suggests a recession will happen in the first or second quarter of this year.”).

[3] See id.

[4] See, e.g., List of recessions in the United States, wikipedia.com (updated Feb. 22, 2024), available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_recessions_in_the_United_States.

[5] See Jennifer Sor, The bond market’s notorious indicator is correctly signaling a coming recession, and the Fed has made a major mistake, the economist who coined the inverted yield curve says, businessinsider.com (Sept. 21, 2023), available at https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/bonds/recession-inflation-us-economy-outlook-inverted-yield-curve-fed-rates-2023-9 (quoting Economist Campbell Harvey as saying, “The indicator is eight out of eight when predicting recessions, and it doesn’t have any false signals.”).

[6] The interest rate spread between the 3-month T-bills and the 10-year treasury notes has historically provided the most accurate gauge for predicting recessions. Nonetheless, economists also look at the interest rate spread between 2-year and 10-year Treasury notes, sometimes called the 2/10 yield curve. See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Minus 2-Year Treasury Constant Maturity, fred.stlouisfed.org (as of Feb. 22, 2024), available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T10Y2Y/. “The 2/10 year yield curve has inverted six to 24 months before each recession since 1955, a 2018 report by researchers at the San Francisco Fed showed. It offered a false signal just once in that time.” David Randall and Davide Barbuscia, US yield curve hits deepest inversion since 1981: What is it telling us?, reuters.com (July 7, 2023), available at https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/several-parts-us-yield-curve-are-inverted-what-does-it-tell-us-2022-11-01/. Of note, the 2/10 yield curve first inverted in April 2022, before the primary 3/10 (3-month versus 10-year) yield curve inverted in October 2022. This suggests that a recession may occur no later than on or about April 2024. However, one cannot preclude the possibility of the delay running longer than 24 months.

[7] See, e.g., James McWhinney, The Impact of an Inverted Yield Curve, Investopedia.com (updated Aug. 20, 2023), available at https://www.investopedia.com/articles/basics/06/invertedyieldcurve.asp (“In normal circumstances, long-term investments have higher yields; because investors are risking their money for longer periods of time, they are rewarded with higher payouts.”).

[8] See id.

[9] See id.

[10] See, e.g., Daniel H. Cooper, Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, and Giovanni P. Olivei, Predicting Recessions Using the Yield Curve: The Role of the Stance of Monetary Policy, Fed. Res. Bank of Boston (Feb. 3, 2020), available at https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2020/predicting-recessions-using-the-yield-curve (“A yield curve inversion can also emerge due to a decline in longer-term interest rates. Investors’ expectations about future economic activity, and the associated expectations about future monetary policy, will drive movements at the longer end of the curve. For example, an anticipated slowdown in the pace of economic activity will put downward pressure on long-term yields, because they are driven by expectations of future short-term rates, and investors recognize that the central bank will have to lower rates eventually if the slowdown materializes. Such a decline in long-term yields can generate a yield curve inversion that is correlated with a future recession to the extent that investors correctly anticipate the downturn.”) see also Daniel Liberto, et al., Inverted Yield Curve: Definition, What It Can Tell Investors, and Examples, Investopedia.com (updated Dec. 4, 2023), available at https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/invertedyieldcurve.asp (“A yield curve inverts when long-term interest rates drop below short-term rates, indicating that investors are moving money away from short-term bonds and into long-term ones. This suggests that the market as a whole is becoming more pessimistic about the economic prospects for the near future.”).

[11] See id.; Daniel H. Cooper, Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, and Giovanni P. Olivei, Predicting Recessions Using the Yield Curve: The Role of the Stance of Monetary Policy, Fed. Res. Bank of Boston, supra.

[12] See id.; Daniel Liberto, et al., Inverted Yield Curve: Definition, What It Can Tell Investors, and Examples, Investopedia.com, supra.

[13] See id.; Daniel H. Cooper, Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, and Giovanni P. Olivei, Predicting Recessions Using the Yield Curve: The Role of the Stance of Monetary Policy, Fed. Res. Bank of Boston, supra.

[14] See id.; Daniel Liberto, et al., Inverted Yield Curve: Definition, What It Can Tell Investors, and Examples, Investopedia.com, supra. For context, U.S. Treasury transferrable offerings include T-bills (maturities of four weeks to one year), treasury notes (maturities of two to ten years), treasury bonds (maturities of twenty or thirty years), floating rate notes (“FRNs”), Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (“TIPS”), and Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities (“STRIPS”). See About Treasury Marketable Securities, treasurydirect.gov, available at https://treasurydirect.gov/marketable-securities/. The U.S. Treasury also offers savings bonds, which are non-transferable. See id.

[15] See, e.g., David Randall and Davide Barbuscia, US yield curve hits deepest inversion since 1981: What is it telling us?, reuters.com, supra (“The yield curve inverts when shorter-dated Treasuries have higher returns than longer-term ones. It suggests that while investors expect interest rates to rise in the near term, they believe that higher borrowing costs will eventually hurt the economy, forcing the Fed to later ease monetary policy.”).

[16] See id.; Jason Fernando, et al., Reinvestment Risk Definition and How to Manage It, Investopedia.com (updated Dec. 21, 2023), available at https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/reinvestmentrisk.asp.

[17] See id.; David Randall and Davide Barbuscia, US yield curve hits deepest inversion since 1981: What is it telling us?, reuters.com, supra.

[18] See id.; Jason Fernando, et al., Reinvestment Risk Definition and How to Manage It, Investopedia.com, supra.

[19] See Daniel H. Cooper, Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, and Giovanni P. Olivei, Predicting Recessions Using the Yield Curve: The Role of the Stance of Monetary Policy, Fed. Res. Bank of Boston, supra (“When risks of a future downturn increase, even with an unchanged modal path for the future course of monetary policy, there can be a ‘flight to quality’ that bids up the price of long-term Treasury bonds and lowers their yield. Thus if a recession materializes, it will be correlated with the inverted yield curve.”); Daniel Liberto, et al., Inverted Yield Curve: Definition, What It Can Tell Investors, and Examples, Investopedia.com, supra.

[20] The Inverted Yield Curve: What It Means and How to Navigate It, YCharts (Aug. 22, 2023), available at https://get.ycharts.com/resources/blog/inverted-yield-curve-what-it-means-and-how-to-navigate-it/.

[21] See id.

[22] See id.

[23] See Wall Street Journal, How a Little-Known Committee Determines When a Recession Begins, youtube.com (Feb. 8, 2023), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VYpyuJAyreM.

[24] See How Do Economists Determine Whether the Economy Is in a Recession?, whitehouse.gov (July 21, 2022), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2022/07/21/how-do-economists-determine-whether-the-economy-is-in-a-recession/.

[25] See, e.g., The Julia La Roche Show, Inventor Of The Most Famous Recession Indicator—The Inverted Yield Curve—Sees Slower Economic Growth, youtube.com (January 23, 2024 Interview with Prof. Campbell Harvey), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HkOXCFKJf0w.

[26] See Probability of US Recession Predicted by Treasury Spread, Fed. Res. Bank of N.Y. (updated Feb. 4, 2024), available at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/capital_markets/Prob_Rec.pdf.

[27] See Matthew Fox, The US now has an 85% chance of recession in 2024, the highest probability since the Great Financial Crisis, economist David Rosenberg says, businessinsider.com (Feb. 12, 2024), available at https://www.businessinsider.com/recession-outlook-financial-crisis-economy-federal-reserve-yield-curve-rosenberg-2024-2.

[28] Id.

[29] See Jeff Cox, Credit card delinquencies surged in 2023, indicating ‘financial stress,’ New York Fed says, cnbc.com (Feb. 6, 2024), available at https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/06/credit-card-delinquencies-surged-in-2023-indicating-financial-stress-new-york-fed-says.html.

[30] Personal Income and Outlays, January 2024, BEA 24-06, bea.gov (Feb. 29, 2024), available at https://www.bea.gov/news/2024/personal-income-and-outlays-january-2024.

[31] The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (as stated above, referred to as “PCE”) is calculated by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (“BEA”). For assessing inflation, and particularly whether inflation is at the desired rate of 2%, the Federal Open Market Committee (“FOMC”) of the Federal Reserve System looks primarily at the core (minus food and energy) PCE inflation rate. Notably, for assessing overall inflation, the FOMC puts more stock in PCE than the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”). Specifically, “[t]he FOMC focused on CPI inflation prior to 2000 but, after extensive analysis, changed to PCE inflation for three main reasons: [t]he expenditure weights in the PCE can change as people substitute away from some goods and services toward others[;] the PCE includes more comprehensive coverage of goods and services[;] and historical PCE data can be revised (more than for seasonal factors only).” James Bullard, President’s Message: CPI vs. PCE Inflation: Choosing a Standard Measure, Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, stlouisfed.org (July 1, 2013), available at https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/july-2013/cpi-vs-pce-inflation–choosing-a-standard-measure.

[32] See Archive, bea.gov, (last modified Feb. 26, 2024) available at https://www.bea.gov/news/archive?field_related_product_target_id=721&created_1=All&title=; see also Federal Open Market Committee, Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, federalreserve.gov (Jan. 30, 2024 reaffirmation of policy), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC_LongerRunGoals.pdf (“The Committee reaffirms its judgment that inflation at the rate of 2 percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate.”).

[33] See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, M2, stlouisfed.org (as of Jan. 23, 2024), available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M2SL#0; see also Jay Blindauer, Government Contracts Inflation Update, blindauerlaw.com (Mar. 16, 2023), available at https://blindauerlaw.com/government-contractor-inflation-update/ (I provided tables showing the since-2020 rise and fall of the inflation rate across the CPI-U, PPI, ECI, and PCE indices). As the aforementioned FRED graph shows, the steep increase of the money supply in 2020 to 2021 occurred at a pace not seen since the start of the graph in 1959. And, inflation is “too much money chasing the available supply of goods and services.” Peter N. Ireland, What Would Milton Friedman Say about the Recent Surge in Money Growth?, mercatus.org (May 2, 2022), available at https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/what-would-milton-friedman-say-about-recent-surge-money-growth.

[34] See, e.g., Greg Iacurci, There is ‘nowhere to hide’ for consumers as inflation hits food, gas, housing, cnbc.com (Mar. 10, 2022), available at https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/10/theres-nowhere-to-hide-for-consumers-as-inflation-hits-food-gas-housing.html.

[35] See Consumer Price Index Summary, bls.gov (Feb. 13, 2024), available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm (showing energy costs down 4.6% over the preceding twelve months, but food is up 2.6%, and shelter is up 6%). “Despite a slowdown in the year-over-year increase, shelter costs continue to put upward pressure on inflation, accounting for over two-thirds of the total increase in all items excluding food and energy.” Fan-Yu Kuo, Inflation Remains Sticky due to Persistent Housing Costs, Nat’l Ass’n of Home Builders, eyeonhousing.org (Feb. 13, 2024), available at https://eyeonhousing.org/2024/02/inflation-remains-sticky-due-to-persistent-housing-costs/. Based on 2022 survey data, Americans are spending, on average, approximately 33% of their annual spend on housing, and approximately 12% on food—and the numbers are even higher for the 60% of Americans not in the top two quintiles. See Share of average annual consumer expenditure on major categories in the United States in 2022, by income quintiles, statistica.com (Sept. 2023), available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/247420/percentage-of-annual-us-consumer-spending-by-income-quintiles/. “U.S. consumers spent an average of 11.3 percent of their disposable personal income on food in 2022— reaching levels similar to the 1980s.” Food Prices and Spending, Economic Research Serv., U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture (contact Anikka Martin), ers.usda.gov (last updated Feb. 14, 2024), available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-prices-and-spending/; Abha Bhattarai, Jeff Stein, Inflation has fallen. Why are groceries still so expensive?, washingtonpost.com (Feb. 2, 2024), available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/02/02/grocery-price-inflation-biden/.

[36] See, e.g., As the U.S. Consumer Goes, So Goes the U.S. Economy, whitehouse.gov (Oct. 20, 2023), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2023/10/30/as-the-u-s-consumer-goes-so-goes-the-u-s-economy/ (“Consumption spending makes up two-thirds of the U.S. economy on average, so as the U.S. consumer goes, so goes the U.S. economy.”); The Julia La Roche Show, Inventor Of The Most Famous Recession Indicator—The Inverted Yield Curve—Sees Slower Economic Growth, youtube.com, supra (during his appearance, Professor Harvey discussed the importance of the consumer and consumer spending in determining whether a recession occurs).

[37] Yuheng Zhan, Troubled commercial real estate loans outstrip reserves at top US banks, businessinsider.com (Feb. 20, 2024), available at https://www.businessinsider.com/commercial-real-estate-delinquent-loans-bank-reserves-office-values-economy-2024-2#.

[38] Patrick Clark, US Commercial Property Foreclosures Spike in January, Bloomberg (Feb. 22, 2024), available at https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/realestate/us-commercial-property-foreclosures-spike-in-january/ar-BB1iJ7wc.

[39] US bankruptcies surged 18% in 2023 and seen rising again in 2024 -report, reuters.com (Jan. 3, 2024), available at https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/us-bankruptcies-surged-18-2023-seen-rising-again-2024-report-2024-01-03/.

[40] Falen Taylor, Mortgage Delinquencies Increase in the Fourth Quarter of 2023, Mortgage Bankers Assoc’n (Feb. 8, 2024), available at https://www.mba.org/news-and-research/newsroom/news/2024/02/08/mortgage-delinquencies-increase-in-the-fourth-quarter-of-2023.

[41] Homes Prices Remain Overvalued in 88% of the U.S., FitchRatings (Dec. 20, 2023), available at https://www.fitchratings.com/research/structured-finance/homes-prices-remain-overvalued-in-88-of-us-20-12-2023.

[42] See Home Price to Median Household Income Ratio (US), longtermtrends.net (showing data up to October 31, 2023), available at https://www.longtermtrends.net/home-price-median-annual-income-ratio/.

[43] See id.

[44] See id.

[45] See Employment Situation Summary, USDL-24-0148, bls.gov (Feb. 2, 2024), available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm.

[46] See Employment Cost Index Summary, USDL-24-0146, bls.gov (Jan. 31, 2024), available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/eci.nr0.htm; see also Employment Cost Index Archived News Releases, bls.gov (last modified Feb. 2, 2024), available at https://www.bls.gov/bls/news-release/eci.htm.

[47] See Christopher D. Cotton and Vaishali Garga, Fed. Res. Bank of Boston, What Is Driving Inflation—Besides the Usual Culprits?, bostonfed.org (July 13, 2023), available at https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2023/what-is-driving-inflation-besides-the-usual-culprits.aspx.

[48] Id.

[49] See Employment Cost Index Summary, Table B-2, Average weekly hours and overtime of all employees on private nonfarm payrolls by industry sector, seasonally adjusted, bls.gov (Feb. 2, 2024), available at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t18.htm.

[50] See Women Drive US Job Gains With More Entering Workforce, bloomberg.com (Feb. 2, 2024), available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/live-blog/2024-02-02/us-employment-report-for-january; see also Monthly length of the average working week of all employees in the United States from January 2022 to January 2024, statistica.com (Feb. 2024), available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/215643/average-weekly-working-hours-of-all-employees-in-the-us-by-month/.

[51] Duke Today, It’s Official: The Yield Curve is Triggered. Does a recession loom on the horizon?, today.duke.edu (published July 1, 2019 in Academics), available at https://today.duke.edu/2019/07/its-official-yield-curve-triggered-does-recession-loom-horizon.

[52] See NBER, Unemployment Rate and Recessions since 1948, nber.org (as of October 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/research/business-cycle-dating.

[53] See Simon Constable, Germany’s Epic Recession Continues: Economy Still Can’t Catch A Break, forbes.com (Aug. 28, 2023), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/simonconstable/2023/08/28/germanys-epic-recession-continues-economy-still-cant-catch-a-break/?sh=47e992d12bd2; Hisako Ueno, Daisuke Wakabayashi, Japan’s Economy Slips Into Recession and to No. 4 in Global Ranking, The New York Times, nytimes.com (Feb. 15, 2024), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/15/business/japan-q4-gdp.html; Dearbail Jordan, Faisal Islam, UK economy fell into recession after people cut spending, bbc.com (Feb. 15, 2024), available at https://www.bbc.com/news/business-68285833.

[54] See Laura He, China has another massive headache now: It can’t stem deflation, cnn.com (Dec. 11, 2023), available at https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/11/economy/china-cpi-deflation-worsens-intl-hnk/index.html; Jason Douglas, In China, Deflation Tightens Its Grip, The Wall Street Journal, wsj.com (Feb. 8, 2024), available at https://www.wsj.com/economy/chinas-consumer-prices-fall-by-more-than-expected-cbaba7ee.

[55] See id.

[56] See 29 U.S.C. § 2102.

[57] 20 C.F.R. § 639.3(a)(1) (emphasis added); see also 29 U.S.C. § 2101(a)(8) (“[T]he term ‘part-time employee’ means an employee who is employed for an average of fewer than 20 hours per week or who has been employed for fewer than 6 of the 12 months preceding the date on which notice is required.”).

[58] Id. at § 2101(a)(2).

[59] Id. at § 2101(a)(3) (emphasis added).

[60] See id. at § 2102(a); see also 20 C.F.R. § 639.7 (contents of a notice).

[61] See 29 U.S.C. § 2102(d).

[62] See id.

[63] Id.

[64] See 29 U.S.C. § 2102(b)(1).

[65] See id. at § 2102(b)(2)(A).

[66] See id. at § 2102(b)(2)(B).

[67] Id. at § 2103(1); see also 20 C.F.R. § 639.5(c).

[68] 29 U.S.C. § 2103(2).

[69] Id. at § 2102(b)(3).

[70] 20 C.F.R. § 639.9(b)(1).

[71] Id. at § 639.9(b)(2).

[72] Hotel Employees & Rest. Employees Int’l Union Local 54 v. Elsinore Shore Assocs., 173 F.3d 175, 185 n.8 (3d Cir. 1999); see also Loehrer v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 98 F.3d 1056, 1062-63 (8th Cir. 1996) (the Government’s termination of the contract was a not reasonably foreseeable business circumstance, even though the contractor was aware that the Government was dissatisfied with the contractor’s performance).

[73] 20 C.F.R. § 639.5(c)(4).

[74] See, e.g., Kinney v. Public Consulting Grp., Inc., 2023 WL 2586277, at 7 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 21, 2023) (“That the Defendants entered into additional contracts with the NYS DOH does not create an expectation of indefinite employment. The continued relationship between Defendants and the NYS DOH is a far cry from the aircraft manufacturer example in 20 C.F.R. § 639.5(c)(4). There, an aircraft manufacturer had an ‘expectation that the contract would continue to be renewed during the foreseeable future.’ 20 C.F.R. § 639.5(c)(4). In contrast, here Defendants and the NYS DOH’s Initiative-specific contract ended—indeed the offer letter provided an expected end date—and they entered into subsequent, different contracts.”).

[75] In re APA Transp. Corp. Consol. Litigation, 541 F.3d 233, 239 (3d Cir. 2008) (quoting Hotel Employees & Rest. Employees Int’l Union Local 54 v. Elsinore Shore Assocs., 173 F.3d 175, 182 (3d Cir. 1999)).

[76] See 29 U.S.C. § 2106.

[77] See DoL Employment and Training Administration, WARN Act, Employer’s Guide to Advance Notice of Closings and Layoffs, www.dol.gov, available at https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/Layoff/pdfs/_EmployerWARN2003.pdf.

[78] See id.

[79] H.R. 6358, 118th Cong. (2023), Fair Warning Act of 2023 (introduced Nov. 9, 2023), govtrack.us, available at https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/118/hr6358/text/ih.

[80] Id.

[81] See, e.g., FAR 16.203-4(a)(4), (b)(6), and (c)(5).

[82] I note that, since March 17, 2022, to assist contractors, GSA has been more flexible with adjustment ceilings under its EPA clauses. See SPE Jeffrey Koses, Ass’t Commissioner Mark Lee, Temporary Moratorium on Enforcement of Certain Limitations Contained in Certain GSA Economic Price Adjustment (EPA) Contract Clauses, Acquisition Letter MV-22-02 (March 17, 2022), available at https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/MV-22-02.pdf; see also GSA Acquisition Letter MV-22-02, Supp. 4 (Feb. 28, 2024) (extending EPA clause changes until December 31, 2024), available at https://www.gsa.gov/system/files/MV-22-02%20with%20sups%201-4.pdf.

[83] See Jay Blindauer, An In-Depth Examination of Inflation Relief for a Government Contractor, blindauerlaw.com (Oct. 10, 2022), available at https://blindauerlaw.com/an-in-depth-examination-of-inflation-relief-for-a-government-contractor/.

[84] See U.S. Debt Clock, usdebtclock.org, available at https://www.usdebtclock.org/# (showing U.S. total debt at $97.7 trillion and U.S. GDP at $27.9 trillion).

[85] “The four components of gross domestic product are personal consumption, business investment, government spending, and net exports.” Kimberly Amadeo, Components of GDP Explained, 4 Critical Drivers of America’s Economy, thebalancemoney.com (updated Jan. 18, 2022), available at https://www.thebalancemoney.com/components-of-gdp-explanation-formula-and-chart-3306015.

[86] See U.S. Debt Clock, usdebtclock.org, supra.

[87] See Keith Bradsher, Why China Has a Giant Pile of Debt, nytimes.com (July 8, 2023), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/08/business/china-debt-explained.html.

[88] See U.S. Debt Clock, usdebtclock.org, supra.

[89] See Michelle Fox, The U.S. national debt is rising by $1 trillion about every 100 days, cnbc.com (Mar. 1, 2024), available at https://www.cnbc.com/2024/03/01/the-us-national-debt-is-rising-by-1-trillion-about-every-100-days.html.

[90] See U.S. Deficit by Year, FiscalData.treasury.gov (last updated Sept. 30, 2023), available at https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-deficit/#us-deficit-by-year; Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, Federal Surplus or Deficit (FYFSD), stlouisfed.org (last updated Oct. 24, 2023), available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSD. “FY” stands for fiscal year.

[91] See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, Federal Surplus or Deficit [-] as Percent of Gross Domestic Product, fred.stlouisfed.org (last updated Feb. 28, 2024), available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSGDA188S (showing that, in 1943, the Federal deficit got as high as 26.8% of GDP—a deficit that, as a percentage of GDP, has not since been repeated). I also note that the Federal Government’s response to the Great Recession involved significant deficit spending, but the Great Recession deficit spending as a percentage of GDP was not as high as for WWII. See also Brendan Greeley, How the US actually financed the second world war, Financial Times (Feb. 13, 2019), available at https://www.ft.com/content/e4eec640-321e-3cfe-9b82-46bacfa4d6bc.

[92] See Stephen Daggett, Costs of Major U.S. Wars, RS22926, Congressional Research Service, at 2 (July 29, 2010), available at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RS22926.pdf; see also U.S. Inflation Calculator, usinflationcalcultor.com, available at https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/. The figures of $4.72 trillion and $5.62 trillion come from taking Mr. Daggett’s FY 2011 figure of $4.104 trillion and running it through the inflation calculator.

[93] See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, Federal Receipts as Percent of Gross Domestic Product, fred.stlouisfed.org (last updated Feb. 28, 2024), available at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFRGDA188S; see also Jay Blindauer, Government Contracts Inflation Update, blindauerlaw.com (Mar. 16, 2023), available at https://blindauerlaw.com/government-contractor-inflation-update/ (I discuss the Hauser line, discovered in 1993 by W. Kurt Hauser).

[94] See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, Federal Receipts as Percent of Gross Domestic Product, supra.

[95] See id.

[96] Brian Faler, U.S. sees biggest revenue surge in 44 years despite pandemic, politico.com (Oct. 12, 2021), available at https://www.politico.com/news/2021/10/12/tax-revenue-surge-pandemic-515792.

[97] See Fed. Res. Bank of St. Louis, FRED, Federal Receipts as Percent of Gross Domestic Product, supra.

[98] See CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034, www.cbo.gov (Feb. 2024), available at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-02/59710-Outlook-2024.pdf.

[99] See id.

[100] See id.

[101] See Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Res. Sys., Open Market Operations, federalreserve.gov (last updated July 26, 2023), available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/openmarket.htm.

[102] See, e.g., Isabella Simonetti, The $24 Trillion Market That Predicts and Influences Interest Rates, wwwnytimes.com (Nov. 3, 2022), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/02/business/treasury-yields-bond-market.html; J.B. Maverick, et al., The Most Important Factors Affecting Mortgage Rates, Investopedia.com (updated Dec. 13, 2023), available at https://www.investopedia.com/mortgage/mortgage-rates/factors-affect-mortgage-rates/ (“One frequently used government bond benchmark to which mortgage lenders often peg their interest rates is the 10-year Treasury bond yield. Typically, MBS sellers must offer higher yields because repayment is not 100% guaranteed as it is with government bonds.”); see also James Chen, Dutch Auction: Understanding How It’s Used in Public Offerings, investopedia.com (Oct. 26, 2022), available at https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/dutchauction.asp (explaining how the U.S. Treasury sells bonds through Dutch auctions); Filip DeMott, Treasury bond auction runs into weak demand amid fears that soaring US debt will overwhelm Wall Street, businessinsider.com (Oct. 12, 2023), available at https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/bonds/treasury-bond-auction-us-debt-crisis-fed-buying-quantitative-tightening-2023-10.

[103] 2 U.S.C. § 900(c)(7) and (8); see also Expenditures in the United States federal budget, wikipedia.com (updated Jan. 25, 2024), available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expenditures_in_the_United_States_federal_budget.

[104] See CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034, supra (based on the 2024 budget numbers).

[105] Amanda Seitz and Hannah Fingerhut, Most oppose Social Security, Medicare cuts: AP-NORC poll, apnews.com (Apr. 7, 2023), available at https://apnews.com/article/social-security-medicare-cuts-ap-poll-biden-9e7395e8efeab68063d741beac6ef24b.

[106] Justin Siken, Record $765B in Federal Contracts Awarded in 2023, highergov.com (Jan. 17, 2024), available at https://www.highergov.com/reports/765b-federal-gov-contract-awards-2023/.

[107] Sam Grey Enters. v. United States, 250 F.3d 755, at 2 (Fed. Cir. 2000).

[108] Tracy v. United States, 55 Fed. Cl. 679, 682 (2003).

[109] See 31 U.S.C. § 1341(a)(1) (“[A]n officer or employee of the United States Government or of the District of Columbia government may not– (A) make or authorize an expenditure or obligation exceeding an amount available in an appropriation or fund for the expenditure or obligation; [or] (B) involve either government in a contract or obligation for the payment of money before an appropriation is made unless authorized by law[.]”); 31 U.S.C. § 1517(a) (“[A]n officer or employee of the United States Government or of the District of Columbia government may not make or authorize an expenditure or obligation exceeding—[ ] an apportionment[.]”); Cessna Aircraft Co., ASBCA No. 43196, 93-1 BCA ¶ 25,511 (Oct. 20, 1992) (denying Government motion to dismiss and affirming that the Board had jurisdiction to hear the contractor’s challenge that the Contracting Officer’s exercise of an option was ineffective because it violated the Anti-Deficiency Act); but see Cessna Aircraft Co., ASBCA No. 43196, 93-3 BCA ¶ 25,912 (Mar. 12, 1993) (nonetheless finding that “the option exercise is not rendered ineffective by obligation of appropriated funds prior to OMB apportionment and prior to DoD allocation of such funds.”).

[110] Salazar v. Ramah Navajo Chapter, 567 U.S. 182, 191 (2012).

[111] See Ferris v. United States, 27 Ct. Cl. 542, 546 (1892) (“A contractor who is one of several persons to be paid out of an appropriation is not chargeable with knowledge of its administration, nor can his legal rights be affected or impaired by its maladministration or by its diversion, whether legal or illegal, to other objects. An appropriation per se merely imposes limitations upon the Government’s own agents; it is a definite amount of money intrusted to them for distribution; but its insufficiency does not pay the Government’s debts, nor cancel its obligations, nor defeat the rights of other parties.”); Dougherty, for Use of Slavens v. United States, 18 Ct. Cl. 496, 503 (1883) (“[W]hen one contract on its face assumes to provide for the execution of all the work authorized by an appropriation, the contractor is bound to know the amount of the appropriation, and cannot recover beyond it; but we have never held that persons contracting with the Government for partial service under general appropriations are bound to know the condition of the appropriation account at the Treasury or on the contract book of the Department. To do so might block the wheels of the Government. The statutory restraints in this respect apply to the official, but they do not affect the rights in this court of the citizen honestly contracting with the Government.”).