Ever since the Supreme Court's decision in Dickinson v. Zurko, patent applicants (and with the advent of inter partes review proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, patentees) have found it difficult to overcome Patent Office determinations of obviousness, due to the deference to factual issues the Zurko case imposed on the Federal Circuit in reviewing PTO decisions. But one Achilles' heel to these difficulties arises over how the PTO construes claims, which remains subject to de novo review (because all the evidence before the Patent Office is inherently intrinsic evidence). And when the Office (through the PTAB) makes an error in construing a claim, the Federal Circuit remains ready to pounce, which was the basis for the Court overturning the PTAB's invalidation on obviousness grounds of Kaken Pharmaceutical's claims in the recent Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. v. Iancu decision.

The case arose in an IPR over all the claims of U.S. Patent No. 7,214,506, which are directed to methods for topically treating fungal infections in human nails. The Board initiated the IPR on petition by Acrux Ltd. and Acrux DDS Pty. Ltd. (who are not party to the appeal), and found all claims of the '506 patent to be unpatentable as obvious.

Claim 1 is representative:

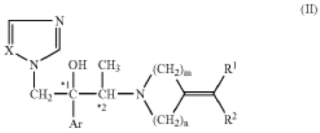

1. A method for treating a subject having onychomycosis wherein the method comprises topically administering to a nail of said subject having onychomycosis a therapeutically effective amount of an antifungal compound represented by the following formula:

wherein, Ar is a non-substituted phenyl group or a phenyl group substituted with 1 to 3 substituents selected from a halogen atom and trifluoromethyl group,

R1 and R2 are the same or different and are hydrogen atom, C1-6 alkyl group, a non-substituted aryl group, an aryl group substituted with 1 to 3 substituents selected from a halogen atom, trifluoromethyl group, nitro group and C1-16 alkyl group, C2-8 alkenyl group, C2-6 alkynyl group, or C7-12 aralkyl group,

m is 2 or 3,

n is 1 or 2,

X is nitrogen atom or CH, and

*1 and *2 mean an asymmetric carbon atom.

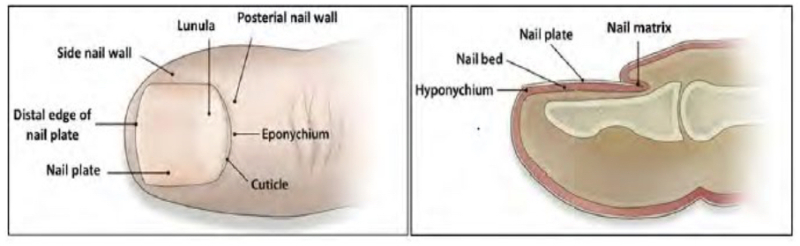

The opinion notes that the specification provides a "series of interlocking definitions" for some of the terms used in the claims. For example, the specification defines "'[o]nychomycosis' [as] a class of 'superficial mycosis' that affects the 'nail of [a] human or an animal'" and defines "superficial mycosis" as "encompass[ing] infections that attack tissues of the 'skin or visible mucosa.'" These definitions are illustrated in a Figure from the '506 patent reproduced in the opinion:

And a specific form of onychomycosis, tinea unguium, fell within the scope of onychomycosis to the extent that the patent used the terms interchangeably. These definitions vary somewhat with what the Federal Circuit termed "common usage" but these differences were not dispositive to the Court's opinion.

The patented methods were directed at solving a problem in the art whereas oral administration of antifungal drugs had undesirable features (long treatment times, unpleasant side effects) while prior art topical approaches were "largely ineffective" due to their inability to permeate the nail plate. As it turns out, the patented invention was effective when the alternative recited for substituent X is nitrogen, and this compound is identified as KP-103; the specification notes that the effectiveness of this compound as an antifungal was known in the art but not its ability to prevent onychomycosis.

Acrux relied on two sets of prior art references in its IPR petition based on obviousness. The first consisted of the three references "Japanese Patent Application No. 10-226639 (JP '639); U.S. Patent No. 5,391,367; and R.J. Hay et al., Tioconazole nail solution—an open study of its efficacy in onychomycosis, 10 CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL DERMATOLOGY 111 (1985)." These references teach onychomycosis treatment using various azole compounds, according to Acrux. The second set of references consisted of "H. Ogura et al., Synthesis and Antifungal Activities of (2R,3R)-2-Aryl-1-az-olyl-3-(substituted amino)-2-butanol Derivatives and Topical Antifungal Agents, 47 CHEM. PHARM. BULL. 1417 (1999) (Ogura); and Abstracts F78, F79, and F80, 36 INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY 113 (1996) (Kaken Abstracts)." These references taught that KP-103 was an effect antifungal agent. Acrux presented six combinations in making its obviousness arguments; the Board in its Final Written Decision (FWD) found the claims obvious over the combination of "JP '639, the '367 patent, and Hay, each in combination with the Kaken Abstracts." Relevant to the Board's FWD and the Federal Circuit's reversal thereof, Kaken argued (and the Board rejected) that the claim term "treating a subject having onychomycosis" means "treating the infection at least where it primarily resides in the keratinized nail plate and underlying nail bed." In the Board's view this construction was too narrow, because onychomycosis was expressly defined to include "superficial mycosis, which in turn is expressly defined as a disease that lies in the skin or visible mucosa" and also that the express definition of the term "nail" in the specification included "the tissue or skin around the nail plate, nail bed, and nail matrix." Based on this construction, the Board held that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to combine the references to achieve the claimed invention. The Board also gave little weight to Kaken's asserted secondary considerations of non-obviousness.

The Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB's judgment based on its incorrect claim construction, vacated the decision and remanded to the PTAB for further consideration based on the correct construction as determined by the Court, in an opinion by Judge Taranto, joined by Judges Newman and O'Malley. Applying the broadest reasonable interpretation standard, the Court held that the disputed claim term, "treating a subject having onychomycosis," means "penetrating the nail plate to treat a fungal infection inside the nail plate or in the nail bed under it," based on the specification and prosecution history. In its analysis of the specification the Federal Circuit opinion recognized that the definition of onychomycosis "links to three other crucial passages in the specification—two that provide express definitions of other terms and one that characterizes another term." Specifically, the specification discloses that onychomycosis is "a kind of the above-mentioned superficial mycosis, in the other word a disease which is caused by invading and proliferating in the nail of human or an animal." The opinion interprets this disclosure to mean, first, that onychomycosis is a nail disease and that it is a superficial mycosis. This does not compel the Board's conclusion that the claim term involves "any part of what is defined as the 'nail,' including parts other than the nail plate or nail bed, such as skin in its ordinary sense" (emphasis in opinion). The opinion finds fault in the Board's interpretation of the term to include "nail plate, nail bed, nail matrix, further side nail wall, posterial nail wall, eponychium and hyponychium which make up a tissue around thereof" which includes skin surrounding the nail. The opinion characterizes as "an unwarranted inference" that a statement that a disease that invades the body can involve (by implication) any part of the body. As pertinent illustration, the opinion states that "[a] disease that invades the nail plate or bed only is still a disease that invades the 'nail' as defined." Thus, "this language alone does not support the Board's conclusion that an infection of any individual structure of the nail constitutes onychomycosis."

The Federal Circuit also found fault in the Board's application of the specifications disclosure regarding onychomycosis as being a "superficial mycosis." Because the specification distinguished such mycosis from "deep" mycosis, the Board interpreted the term to mean fungal infection of the skin in contrast to Kaken's limitation to infections of the nail. The panel found this interpretation contrary to express disclosure in the specification distinguishing skin from nail, whereby characterization in the specification regarding the term "superficial mycosis" does not compel a construction where "every type of superficial mycosis affects every type of 'skin' structure."

The panel found other portions of the specification that supported Kaken's construction, wherein an "effective" topical treatment would need to penetrate the nail plate. The significance of this disclosure for the panel is that "[a] patent's statement of the described invention's purpose informs the proper construction of claim terms, including when the task is to identify the broadest reasonable interpretation," citing In re Power Integrations, Inc., 884 F.3d 1370, 1376–77 (Fed. Cir. 2018). And if the term was to be properly construed under the Board's interpretation, many of the recited features of the invention (such as "high activity in [the] nail plate") would be unnecessary, according to the panel. And, relevant perhaps to the Board's reaction on remand, the opinion also notes that the Board had a "flawed understanding of the relationship between onychomycosis and tinea unguium" that contributed to its claim construction error.

Turning to the prosecution history, the Federal Circuit's opinion states there is "decisive support for limiting the claim phrase at issue to a plate-penetrating treatment of an infection inside or under the nail plate." This support includes rejection, on obviousness-type double patenting grounds, over a parent application directed to using KP-103 to treat "mycosis." In responding to this rejection, Kaken expressly asserted the distinction between mycosis and onychomycosis to be that "[o]nychomycosis is a condition that specifically affects the nail plate" and that the invention "shows the unexpected ability of an azolylamine derivate to penetrate nail and be retained by the nail" (emphases in opinion). The Examiner expressly noted his reliance on these distinctions in his "Reasons for Allowance," stating "unexpectedly and in contrast to previously evaluated compositions/methods, the instantly claimed method cures the onychomycosis because the medicament upon direct administration to the nail, penetrates through the nail plate and eradicates the infection at the site" (emphasis in opinion). The consequence of this sequence of events during prosecution is dispositive, according to the opinion:

This exchange would leave a skilled artisan with no reasonable uncertainty about the scope of the claim language in the respect at issue here. Kaken is bound by its arguments made to convince the examiner that claims 1 and 2 are patentable. See Standard Oil[ v. American Cyanamid Co., 774 F.2d 448,] 452 (Fed. Cir. 1985). Thus, Kaken's unambiguous statement that onychomycosis affects the nail plate, and the examiner's concomitant action based on this statement, make clear that "treating onychomycosis" requires penetrating the nail plate to treat an infection inside the nail plate or in the nail bed under it.

The Board's disregard of these aspects of the prosecution history raises a significant question regarding whether the Board considers mere institution of an IPR as evidence that the prosecution history is necessarily flawed, its consequence having resulted in an improvidently granted patent. And any such implied disregard for the prosecution history raises conflicts at least with proper claim construction that can, as here, result in the Board coming to the wrong conclusion on patentability.

The Federal Circuit reversed the Board's obviousness determination based on its erroneous claim construction, finding in the FWD statements interpreting how a skilled worker would have applied the asserted prior art that relied on this construction. The same error affected the Board's consideration of Kaken's asserted objective indicia of non-obviousness (inter alia, that there was no nexus between these indicia and the claims). The Court remanded, based on precedent including Arista Networks, Inc. v. Cisco Sys., Inc., 908 F.3d 792, 798 (Fed. Cir. 2018), and Dell Inc. v. Acceleron, LLC, 818 F.3d 1293, 1300 (Fed. Cir. 2016), while expressing no opinion on the outcome of the IPR when the Board applies the properly construed claims mandated by the Court's opinion.

Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. v. Iancu (Fed. Cir. 2020)

Panel: Circuit Judges Newman, O'Malley, and Taranto

Opinion by Circuit Judge Taranto