On August 23, in SkinMedica, Inc. v. Histogen Inc., the Federal Circuit determined that the District Court for the Southern District of California did not err in construing the phrase "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions" in the claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,372,494 and 7,118,746, and therefore affirmed the District Court's grant of summary judgment of noninfringement to Defendants-Appellees Histogen, Inc., Histogen Aesthetics, and Gail Naughton ("Histogen").

The '494 and '746 patents, which are owned by Plaintiff-Appellant SkinMedica, Inc., relate to methods for producing pharmaceutical compositions containing novel conditioned cell culture medium compositions and uses for such compositions. During prosecution of the '494 patent, the claims were limited to pharmaceutical compositions comprising cell culture medium conditioned by animal cells cultured in three-dimensions in order to overcome an anticipation rejection based on a reference disclosing a pharmaceutical composition comprising cell culture medium conditioned by animal cells grown in two-dimensions. Claim 1 of the '494 patent, which is representative, recites:

The '494 and '746 patents, which are owned by Plaintiff-Appellant SkinMedica, Inc., relate to methods for producing pharmaceutical compositions containing novel conditioned cell culture medium compositions and uses for such compositions. During prosecution of the '494 patent, the claims were limited to pharmaceutical compositions comprising cell culture medium conditioned by animal cells cultured in three-dimensions in order to overcome an anticipation rejection based on a reference disclosing a pharmaceutical composition comprising cell culture medium conditioned by animal cells grown in two-dimensions. Claim 1 of the '494 patent, which is representative, recites:

1. A method of making a composition comprising:

(a) culturing fibroblast cells in three-dimensions in a cell culture medium sufficient to meet the nutritional needs required to grow the cells in vitro until the cell culture medium contains a desired level of extracellular products so that a conditioned medium is formed;

(b) removing the conditioned medium from the cultured cells; and

(c) combining the conditioned medium with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier to form the composition.

(emphasis in opinion).

Prior to issuance, the claims with the three-dimensional culturing limitation were rejected as obvious in view of two references, one of which discloses a three-dimensional skin culture system that uses a three-dimensional matrix to culture a variety of cells. To overcome this rejection, the inventors argued that "the conditioned medium from cells cultured in three-dimensions has desirable properties not exhibited by medium conditioned by cells cultured [in] two dimensions" and that the references on which the obviousness rejection was based did not disclose that sustained proliferation of the cells in culture is a result of factors or components of the conditioned medium.

In 2009, SkinMedica filed suit against Histogen for producing dermatological products according to methods covered by the claims of the '494 and '746 patents. The District Court construed the phrase "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions" in the claims as meaning "growing . . . cells in three dimensions (excluding growing in monolayers or on microcarrier beads)." The District Court reasoned that the inventors acted as their own lexicographers, defining "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions" away from its ordinary meaning by consistently distinguishing beads from three-dimensional cultures in the specification. Following the District Court's construction, Histogen moved for summary judgment of noninfringement, which the Court granted, finding that Histogen's process "uses beads, [which] cannot infringe the disputed claim element as construed."

In 2009, SkinMedica filed suit against Histogen for producing dermatological products according to methods covered by the claims of the '494 and '746 patents. The District Court construed the phrase "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions" in the claims as meaning "growing . . . cells in three dimensions (excluding growing in monolayers or on microcarrier beads)." The District Court reasoned that the inventors acted as their own lexicographers, defining "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions" away from its ordinary meaning by consistently distinguishing beads from three-dimensional cultures in the specification. Following the District Court's construction, Histogen moved for summary judgment of noninfringement, which the Court granted, finding that Histogen's process "uses beads, [which] cannot infringe the disputed claim element as construed."

On appeal, SkinMedica raised a single point of error, arguing that the District Court erroneously excluded beads from the definition of "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions." In finding that the District Court did not err in construing this phrase, Judge Prost, writing for the majority, states that:

The specification clearly proves that the patentees defined the three-dimensional culturing required by the claims to exclude culturing with beads, because the patent expressly confines culturing with beads to two-dimensional culturing. Whether viewed as a matter of disclaimer or of lexicography, the result is the same: the kind of three-dimensional culturing protected by the patent excludes use of beads. Because the accused method employs beads, it cannot infringe the patents in suit.

The majority opinion also states that:

In the written description, the patentees plainly and repeatedly distinguished culturing with beads from culturing in three-dimensions. They expressly defined the use of beads as culturing in two-dimensions. And they avoided anticipatory prior art during prosecution by asserting that the conditioned medium produced by two-dimensional cultures was inferior and chemically distinct from the conditioned medium produced by three-dimensional cultures.

Judge Prost notes that the specification includes four relevant references to "beads" in the specification (the parties agreed that a fifth reference was not relevant), and indicated that "[i]n each and every one of those four references, the patentees clearly distinguish culturing with beads from culturing in three-dimensions." The four references are as follows (with emphasis from the majority opinion):

[1] Conditioned medium contains many of the original components of the medium, as well as a variety of cellular metabolites and secreted proteins, including, for example, biologically active growth factors, inflammatory mediators and other extracellular proteins. Cell lines grown as a monolayer or on beads, as opposed to cells grown in three-dimensions, lack the cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions characteristic of whole tissue in vivo.

[2] Cell lines grown as a monolayer or on beads, as opposed to cells grown in three-dimensions, lack the cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions characteristic of whole tissue in vivo. Consequently, such cells secrete a variety of cellular metabolites although they do not necessarily secrete these metabolites and secreted proteins at levels that approach physiological levels. Conventional conditioned cell culture medium, medium cultured by cell-lines grown as a monolayer or on beads, is usually discarded or occasionally used in culture manipulations such as reducing cell densities.

[3] The present invention relates to novel compositions comprising any conditioned defined or undefined medium, cultured using any eukaryotic cell type or three-dimensional tissue construct and methods for using the compositions. The cells are cultured in monolayer, beads (i.e., two-dimensions) or, preferably, in three-dimensions.

[4] The cells may be cultured in any manner known in the art including in monolayer, beads or in three-dimensions and by any means . . . .

With respect to these references, Judge Prost indicates that the "reference[s] to beads in the written description [can be read as] clear and unmistakable statement[s] that bead cultures are not the three-dimensional cultures the inventors require in their claimed methods." She also notes that "[t]he inventors go to great lengths (in over twenty-five columns of text in the specification) to explain dozens upon dozens of different ways to culture cells in three-dimensions, yet do not mention beads once in any of them." In summary, Judge Prost states that:

[A]lthough the inventors never explicitly redefined three-dimensional cultures to exclude the use of beads, their implicit disclaimer of culturing with beads here was even "so clear that it equates to an explicit one." Thorner [v. Sony Computer Entm’t Am. LLC], 669 F.3d at 1368. Without fail, each time the inventors referenced culturing with beads in the specification, they unambiguously distinguished that culture method from culturing in three-dimensions. Every time they included beads in a list of methods for culturing cells, the inventors indicated that bead cultures were an alternative to three-dimensional cultures (by using the disjunctive "or") or distinct from three-dimensional cultures (by using the disjunctive phrase "as opposed to"). . . . And the patentees expressly defined culturing in beads as culturing cells in "two-dimensions," which excludes that method from the three-dimensional culturing required by the claims.

Thus, she concludes that "[i]t is therefore clear from the intrinsic record that, although the inventors never explicitly redefined 'culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions' to exclude the use beads, they affected a clear implicit disclaimer of culturing with beads from the scope of their claimed invention."

Judge Prost notes that SkinMedica asserted four reasons for not finding a disclaimer of beads. With respect to SkinMedica's first reason -- that the patentees defined "three-dimensional framework" broadly enough to encompass the use of beads -- Judge Prost indicates that this "theory misses the mark" because it would lead to a conclusion that even a monolayer culture would qualify as three-dimensional. SkinMedica next argued that the Doyle reference was incorporated by reference into the specification, and that this reference "expressly discusses the use of beads to culture cells in three dimensions." However, Judge Prost disagreed, finding that the Doyle reference does not expressly discuss culturing beads in three-dimensions.

SkinMedica also argued that a different reference (the Seldon patent) "expressly acknowledges that three-dimensional culturing with beads provides the same inherent advantages -- i.e., mimicking an in vivo environment -- as other three-dimensional culturing." However, the majority opinion points out that SkinMedica improperly relied on the Seldon patent because it raised this reference for the first time in its reply brief. With respect to this reference, Judge Prost explains that:

SkinMedica crafts a nuanced theory about cell culturing with beads by simply quoting a few short disjointed phrases from the lengthy reference. Yet it has provided no context for those quotes or any reasoning for its conclusions past the quotes themselves. And because it waited until its reply brief on appeal to first mention Seldon, neither the district court nor Histogen have had an opportunity to fully discuss the importance of the disclosures in the reference. . . . SkinMedica's tardiness has so shaded what light Seldon may have shed on the relevant art here that we cannot fairly consider it. We simply cannot decipher the import of the reference without adequate context. SkinMedica has waived its ability to rely on the reference for claim construction purposes on appeal.

Finally, with respect to SkinMedica's argument that the testimony of its expert established that skilled practitioners understood that three-dimensional culturing could be performed using beads, and that culturing using beads in three-dimensions produces the same benefits over two-dimensional culturing that the patents describe, Judge Prost responds that "[t]he first point from Dr. Salomon's testimony . . . simply confirms an assumption we already made during our analysis of the intrinsic record." As for the second point, she notes that "Dr. Salomon's opinions are unhelpful to our analysis here," adding that "[t]hey are conclusory and incomplete; they lack any substantive explanation tied to the intrinsic record; and they appear to conflict with the plain language of the written description."

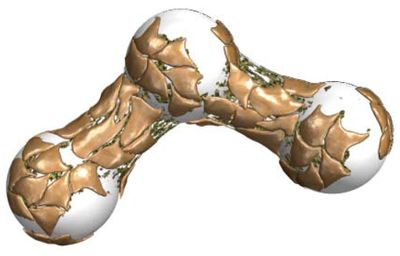

Writing in dissent, Chief Judge Rader argues that "the patentees did not disavow the ordinary meaning of 'culturing . . . cells in three-dim ensions' to exclude the use of beads." He notes that cells can be cultured on beads in either two- or three-dimensions, providing graphic representations of each:

ensions' to exclude the use of beads." He notes that cells can be cultured on beads in either two- or three-dimensions, providing graphic representations of each:

According to the Chief Judge, the four references to beads in the specification discussed by both the District Court and the majority opinion "do not amount to an unmistakable and unambiguous disavowal."  In particular, he explains that "the patentees used the disjunctive phrase 'as opposed to' to distinguish 'cells grown in three-dimensions' from cells grown 'on beads' in two-dimensions," adding that "[t]he phrase '[c]ell lines grown as a monolayer or on beads' can reasonably be interpreted to mean cells cultured as a monolayer, or, as a monolayer on beads."

In particular, he explains that "the patentees used the disjunctive phrase 'as opposed to' to distinguish 'cells grown in three-dimensions' from cells grown 'on beads' in two-dimensions," adding that "[t]he phrase '[c]ell lines grown as a monolayer or on beads' can reasonably be interpreted to mean cells cultured as a monolayer, or, as a monolayer on beads."

Because the four references in the specification "do not meet the exacting standard imposed by this court's precedent [for an unmistakable and unambiguous disavowal]," the Chief Judge states that he would find that the patentees did not unmistakably and unambiguously disavow the ordinary meaning of "culturing . . . cells in three-dimensions" to exclude the use of beads, and would have therefore reversed the District Court's grant of summary judgment.

SkinMedica, Inc. v. Histogen Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2013)

Panel: Chief Judge Rader and Circuit Judges Clevenger and Prost

Opinion by Circuit Judge Prost; dissenting opinion by Chief Judge Rader