The decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in favor of Senior Party the Broad Institute, Harvard University, and MIT (collectively, "Broad") and against Junior Party the University of California/Berkeley, the University of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (collectively, "CVC") sixteen months ago in the latest CRISPR interference No. 106,115 is the subject of appeal from both parties. CVC filed its brief on September 20, 2022; Broad (discussed herein) filed its (corrected) Responsive Brief (which included a Contingent Cross-Appeal in the event the Federal Circuit did not affirm the PTAB's decision below) on February 15, 2023.

Broad's brief is based on two arguments. The first is one they have advanced since their earlier Interference against CVC (Interference No. 106,048), where the Board held (and the Federal Circuit affirmed) that there was no interference-in-fact between Broad's claims to methods of performing CRISPR-mediated DNA cleavage in eukaryotic cells and CVC's claims for CRISPR methods not limited to cell type. The rationale in the '048 interference that was asserted in this interference is that being able to perform CRISPR in eukaryotic cells was so inherently unpredictable that only by actual reduction to practice could a party show complete conception. (It may be remembered that during the Preliminary Motions phase of the '115 interference Broad advocated this reasoning as an instance of "simultaneous conception and reduction to practice," which they later did not pursue.) Broad includes this list of the litany of inherent uncertainties recited throughout this and the earlier '048 Interference:

(1) delivery into the eukaryotic cell,

(2) expression of the components in the cell,

(3) surviving eukaryotic defense mechanisms,

(4) formation of the protein:RNA complex,

(5) toxicity to the cell,

(6) proper protein folding,

(7) localization in the nucleus,

(8) access to the desired DNA target in the chromatin, and

(9) cleavage of the DNA

based on (Broad argues) "a 1.5-billion-year evolutionary divergence," including:

• Eukaryotic cells have a nucleus protecting genomic DNA, organized into discrete structures, called chromosomes, composed of a protein/DNA complex called chromatin;

• Prokaryotic cells lack nearly all the structural organization found in eukaryotic cells, such as a nucleus and chromatin, that functions to organize and protect DNA;

• Eukaryotic cells employ different cellular machinery and mechanisms to express genes, relying on proteins and complexes not found in prokaryotic cells. Those proteins and complexes can be essential to the proper transcription and translation of genetic material;

• Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells have different environments, including different intracellular temperatures, ion concentrations, and pH; [and]

• Prokaryotic systems expressed in eukaryotic cells are often destroyed by native eukaryotic defense mechanisms

(citations to the record omitted).

The second argument was directed to CVC's incomplete conception (as held by the PTAB), based on evidence that CVC's efforts to reduce eukaryotic CRISPR to practice involved "extensive research, experiment, and modification" based in part on the experimental record and in part on CVC's improvident e-mails and other documentary evidence that (Broad argues) illustrates this incomplete conception. The brief focuses on the factual determinations made by the Board which, under In re Gartside, 203 F.3d 1305 (Fed. Cir. 2000), and Dickenson v. Zurko, 119 S.Ct. 1816 (1999), are subject to deference before the Federal Circuit.

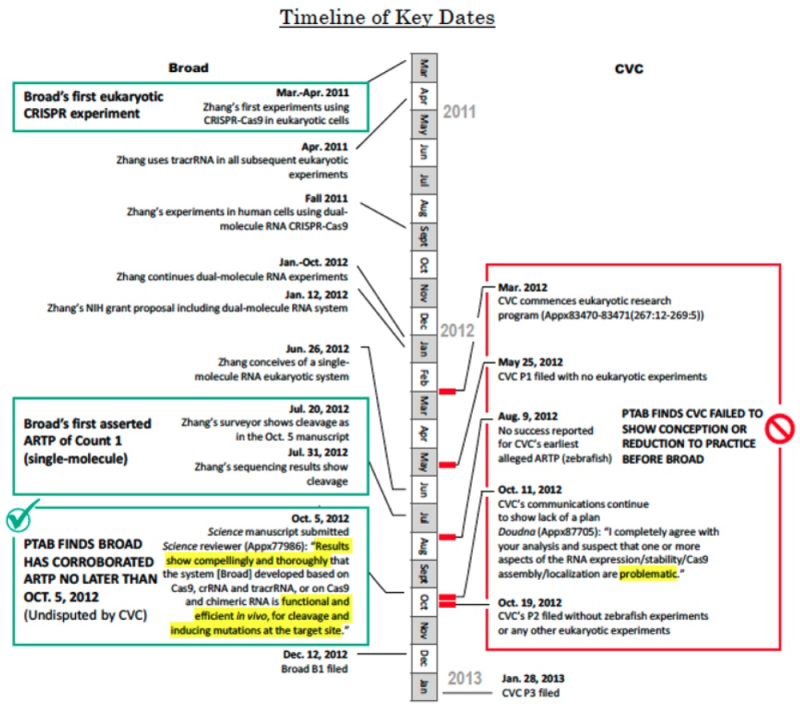

The brief provides a timeline illustrating Broad's comparison between its own conception and reduction to practice with CVC's in a revised diagram related to one advanced before the PTAB:

Broad primary legal argument regarding why the Federal Circuit should affirm the Board's decision is that the PTAB applied the standard enunciated in Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1228 (Fed. Cir. 1994), properly, that conception "is complete only when the idea is so clearly defined in the inventor's mind that only ordinary skill would be necessary to reduce the invention to practice, without extensive research or experimentation" and "conception is not complete if the subsequent course of experimentation, especially experimental failures, reveals uncertainty that so undermines the specificity of the inventor's idea that it is not yet a definite and permanent reflection of the complete invention as it will be used in practice" (emphasis in brief). The brief relies for its argument upon these three factual findings by the Board:

1. That the CVC inventors and corroborators were of at least ordinary skill in the art and that they engaged in a "prolonged period of extensive research, experiment, and modification" which was contrary to the Burroughs standard of "the exercise of ordinary skill without extensive research and experimentation."

2. That the CVC's inventors idea fell squarely within Burroughs standard of incomplete conception, saying:

[W]e are persuaded that the communications surrounding these experiments reflect "uncertainty that so undermines the specificity of the inventor's idea that it [was] not yet a definite and permanent reflection of the complete invention as it [would] be used in practice."

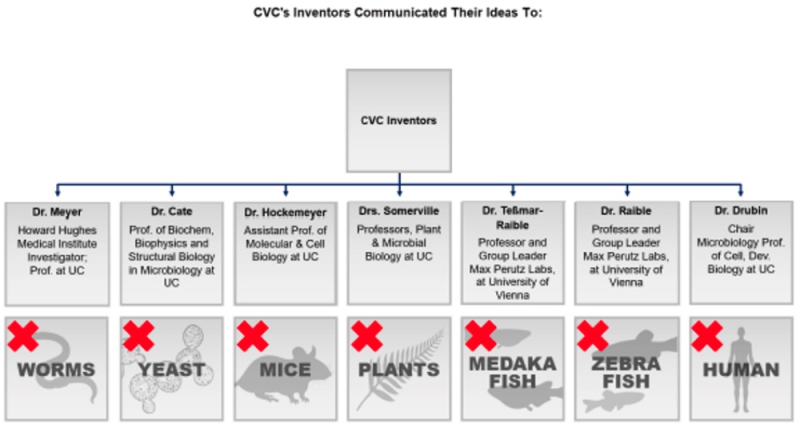

The brief Illustrates as follows this "veritable who's-who of eukaryotic-genome-editing experts—working with CVC inventors using cells from worms, yeast, mice, plants, medaka fish, zebrafish, and humans" who failed to reduced CVC's conception of eukaryotic CRISPR either entirely or not without extensive research, experiment, and modification:

Broad's illustration is in stark contrast to CVC's brief, which emphasizes the lack of ordinary skill in a graduate student that worked unsuccessfully throughout the summer of 2012 to reduce eukaryotic CRISPR to practice followed by success when these experiments were performed by a second graduate student (implied to be of greater skill in the art to explain her success).

Also in this regard the brief further addresses CVC's argument that the amount of time during which their inventors worked to reduce the invention to practice was "only four months," stating that the CVC researchers engaged in "extensive research, experiment, and modifications" during that time and that the inventors' own communications showed that they lacked a "settled plan" for reducing eukaryotic CRISPR to practice, conducted "ill-fated experiments" and did not have "a definite and permanent idea of how to address the obstacles they encountered."

3. CVC offered no evidence of such a "definite and permanent idea" of an operative CRISPR system for cleaving eukaryotic DNA in vivo, Broad emphasizing the PTAB credibility determinations and "finding that the contemporary evidence contradicted CVC's present-day declaration testimony" regarding the routine nature of reducing sgRNA-comprising CRISPR to practice once the CVC inventors conceived of the sgRNA embodiments. Broad also noted that the PTAB rejected CVC's attempts to use success by others as inuring to their benefit or showing they had conception.

As in the '048 Interference the underlying context of Broad's argument is the potential impediments in getting a prokaryotic system -- CRISPR -- to be functional in a eukaryotic cells and that CVC's failures to do so (in the context of contemporaneous evidence that CVC's inventors did not believe their attempts at reduction to practice were successful) was evidence of incomplete conception, as the PTAB held.

The Broad brief addresses CVC's arguments of PTAB legal error by arguing that CVC never raised the issue before the Board that their conception would be complete if no further invention was required, stating that CVC relied on Burroughs before the Board and is not asserting this standard now because the PTAB did not agree with them. Further, Broad argues, regarding CVC's argument that the PTAB imposed a "need to know" requirement, such a requirement is not part of the PTAB's "23-page discussion" and indeed that the PTAB stated the opposite. (In its brief CVC acknowledges that the Board stated that it did not "base [its] decision on a lack of reasonable expectation of success by the CVC inventors" but that the PTAB "contradicted that standard as quickly as it articulated it.") Broad argues that "CVC ignored the functional eukaryotic system limitation [in the Count] in an effort to strip Count 1 down to simply sgRNA" (which is true, up to a point.)

Broad's legal arguments revolve around their contentions that Broad achieved undisputed reduction to practice prior to CVC and thus were presumptively the first to invent, and that CVC's difficulties in reducing the invention to practice exhibited their incomplete conception. Broad's brief argues that the record provides substantial evidence supporting the PTAB's decision and thus deserves deference from the Federal Circuit. While Broad argues the facts more than citing extensive interference precedent the brief expressly recites the following points regarding the Board's factual determinations:

1. Persons of at least ordinary skill were unable to reduce the CVC inventors' ideas to practice without extensive experimentation

This argument focuses on factual determinations made by the PTAB and the support in the record for them, and in particular rebuts CVC's arguments of the incompetent graduate student (Cheng) with the "scores of emails between Doudna/Jinek and Cheng regarding the failed human cell experiments from April to October 2012" that Broad argues shows "near-constant communication with Cheng, directing him on exactly what experiments to perform and setting the parameters." Moreover the brief names as "these skilled artisans" Drubin, Cheng, Doudna, Charpentier, Jinek, Chylinski, and Raible, all of whom failed to reduce to practice despite "extensive research, experiment, and modification," the brief stating that this is "powerful evidence" of incomplete conception. The brief in particular cites to evidence regarding microinjection experiments with worms and "months of failure" (as shown in the expanded graphic above) and states that "a 2013 publication by Doudna and Meyer acknowledged that it was not until they obtained guidance from Broad's Cong 2013 article—and used Zhang's eukaryotic CRISPR-Cas9 system with the dual-molecule RNA configuration—that they achieved any success."

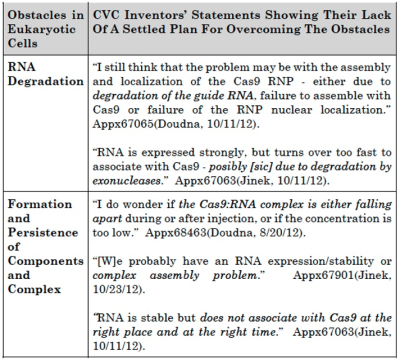

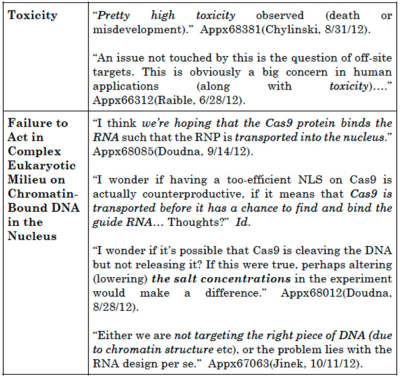

2. CVC's inventors expressed uncertainty that so undermined the specificity of their idea that it was not a definite and permanent reflection of the complete invention

These arguments are based on Burroughs and its definition of incomplete conception as recited above, in addition to citing Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v. W.L. Gore & Assocs., Inc., 776 F.3d 837, 845 (Fed. Cir. 2015); Univ. of Utah v. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft Zur Forderung Der Wissenschaften E.V., 734 F.3d 1315, 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2013); and Dawson v. Dawson, 710 F.3d 1347, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2013), in support of its incomplete conception argument.

The brief states that "in the months following [CVC's] alleged conception [CVC inventors] expressed uncertainty, doubt, and confusion, and proposed ever-shifting plans to try to overcome their failures." The brief also provides this table to illustrate the inventors' contemporary statements regarding the obstacles they were unable to overcome:

From this evidence Broad argues that "[t]hese were not minor problems or thoughts to optimize a definite and permanent idea—they are fundamental obstacles to achieving a functional eukaryotic system."

3. CVC's inventors lacked a clear plan for overcoming the many obstacles to achieving a functional eukaryotic system

This argument is a repetition of Broad's earlier argument that instead of a defined plan CVC provided "a laundry-list of techniques that one might use in a research project attempting to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 to eukaryotic cells" (while characterizing the Jinek March 1, 2012 lab notebook page as "a cartoon"). The brief reminds the Court of the "multiple credibility determinations" made against CVC by PTAB which Broad says on appeal are "virtually unassailable," citing Charles G. Williams Const., Inc. v. White, 326 F.3d 1376, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2003). These include the familiar litany of improvident contemporaneous statements by Doudna and team regarding experimental difficulties encountered in trying to reduce to practice.

Addressing CVC arguments regarding other researchers success the brief asserts that PTAB properly disregarded these efforts as support for the completeness of CVC's conception because the work of independent labs did not establish CVC conception, especially Broad's own (for which the brief asserts that Broad's success was due to their successful dgRNA-comprising CRISPR embodiments and not CVC's sgRNA). Broad also argues that their inventors had "already determined the technical features for creating a functional eukaryotic system" before being informed of sgRNA, and says Broad had demonstrated sgRNA is not necessary for eukaryotic CRISPR (albeit without citation to the record). With regard to these other labs Broad argues that CVC provided no evidence that these labs were independent of Broad (indicating some were affiliated, for example the Church lab although the brief does not specifically make this identification) or whether these researchers were of extraordinary skill in the art, or that these labs may have encountered obstacles of their own that they overcame. Broad's brief also addresses CVC's argument that the PTAB did not identify any differences between the system Broad used successfully that CVC did not, on the basis that the finding was "based on the eminently reasonable inference that the PTAB drew from Broad's success in contrast to CVC's many months of abject experimental failures" (raising the questions CVC's brief raised about the balance between inventive conception and the skilled mechanic).

Broad's brief rebuts CVC's reliance on Acromed Corp. v. Sofamor Danek Grp., Inc., 253 F.3d 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2001), on the grounds that this decision relied on Sewall for the same standard in Burroughs, and Barba v. Brizzolara, 104 F.2d 198, 202 (C.C.P.A. 1939), which Broad distinguished on its facts because in that case the inventors had worked together and the decision involved deciding who was entitled to inventorship.

Finally with regard to the question of incomplete conception the brief addresses these specific CVC allegations:

1. CVC's criticism of the PTAB for finding the CVC inventors' failed eukaryotic experiments relevant to conception is legally incorrect, because CVC had asserted that their conception was complete because reduction to practice used routine and well-established techniques, which is contrary to their repeated failures and contemporary statements.

2. CVC's arguments from their alleged conception to alleged reduction to practice is contrary to the PTAB's findings, which are all supported by substantial evidence, including that the PTAB found evidence of repeated failures and contemporary statements regarding different ways to reduce to practice. These findings are due deference (again rebutting the "blame the graduate student" argument because of evidence of supervision by the named inventors).

3. There is no basis for ignoring these contemporaneous communications that document the CVC inventors' lack of a plan to reduce their conception to practice; in this section Broad attacks amici for having "ties to Doudna" (because she was a postdoc in Tom Cech's lab and because Regeneron is "heavily invested in Doudna's CRISPR company), and further relies on PTAB statements in its decision that CVC did not rebut their inventors' contemporary statements in its Reply brief below.

Broad's arguments in rebuttal of CVC's originality argument is that sgRNA is not the whole invention, stating that "[t]he only element of Count 1 [that Broad inventor] Zhang learned from CVC's public disclosures in June 2012 was the sgRNA species—a configuration that is neither necessary nor sufficient for a functional eukaryotic system."

As for the APA violations asserted in CVC's brief, Broad reiterates its reliance on the extensiveness of the PTAB's decisions (180 pages, which must include all the Priority Motion decisions), the "hundreds of record citations," and "numerous credibility findings," and rebuts CVC's citation of their inventors winning the Nobel Prize by saying "the Nobel committee did not consider or reach any conclusion about invention of the eukaryotic subject matter of Count 1 under U.S. patent law." The brief specifically addresses CVC arguments that PTAB's rejection of microinjection arguments was arbitrary and capricious because "the real-world failures using microinjection in worms and zebrafish demonstrate that microinjection did not overcome the hurdles to eukaryotic uses." Broad further cites its own expert's testimony that microinjection had failed in attempts to get earlier prokaryotic-derived systems for DNA cleavage to work in eukaryotic cells. "Rejecting CVC's argument[s] does not violate APA" provides a succinct synopsis of Broad's position in its brief.

Finally, Broad argues that substantial evidence supported PTAB's determination not to give CVC priority to P1 and P2 provisionals, stating that PTAB relied on the "highly unpredictable" state of the art, using the same arguments that were made in the '048 Interference. These arguments include that there was no disclosure of working example (in the context of the later failures), citing:

Broad has persuaded us that absent results of a successful working example, the lack of discussion of PAM sequences, or sample target DNA sequences, the lack of special instructions or conditions necessary to accommodate the eukaryotic cellular environment, and the lack of a discussion of whether access to chromatin could hinder CRISPR-Cas activity would have indicated to those of ordinary skill in the art that the P1 applicants were not in possession of an embodiment of Count 1.

The brief argues that PTAB applied the correct written description standard (another question of fact) in the context of "the nature of the subject matter and the art—highly unpredictable," wherein the PTAB cited Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1357-58 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc). And Broad cited these three categories of substantial evidence that support PTAB's findings:

1. Evidence that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been aware of the many reasons why prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas might not work in eukaryotic cells, reciting the familiar litany of such reasons;

2. Evidence of prior art failures to adapt other prokaryotic-derived DNA cleavage systems to eukaryotic cells, including TALENS, ZNF, and Group II introns in particular; and

3. Contemporaneous statements of CVC's inventors "indicating doubt that a CRISPR-Cas9 system would work in eukaryotic cells"

After completing its arguments countering CVC's opening brief, Broad provides its affirmative arguments in support of its appeal (contingent on the Federal Circuit reversing or vacating the PTAB's decision below). The gist of these argument is that the PTAB erred in limiting "guide RNA" to sgRNA based on claim construction properly performed using the plain and ordinary meaning of the term. The legal bases for this argument include that "claim terms [in an interference should] receive their broadest reasonable interpretation," citing Dionex Softron GmbH v. Agilent Technologies, Inc., 56 F.4th 1353, 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2023); that "[t]he patentee may deviate from plain meaning only by including 'expressions of manifest exclusion or restriction, representing a clear disavowal of claim scope,'" citing Thorner v. Sony Computer Entertainment Amer. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2012); and "[a]bsent a clear disavowal or contrary definition in the specification or the prosecution history, the patentee is entitled to the full scope of its claim language," citing Home Diagnostics, Inc. v. LifeScan, Inc., 381 F.3d 1352, 1358 (Fed. Cir. 2004). The brief (with some irony) cites the Jinek 2012 reference as providing the ordinary and customary meaning of guide RNA to include dgRNA and sgRNA and that the Broad specification is consistent in this definition.

Broad requests the Federal Circuit vacate the PTAB's denials of their Preliminary Motion 2 and Motion 3, and remand for consideration that would shield Broad from losing priority to its claims to dgRNA-comprising eukaryotic CRISPR embodiments.