While much has been written about the effect of the post-grant review provisions of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (2012) in invalidating U.S. patents, the change in the law most responsible for how easy it has become to invalidate patents is arguably the Supreme Court's decision in Dickinson v. Zurko (1999). That decision, which applied the provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act (1948) to judicial review of U.S. Patent and Trademark Office determinations mandated that disgruntled patentees and patent applicants show that factual decisions by the Office are not supported by substantial evidence in order to overturn these decisions. These considerations extend even to questions of law like obviousness, which are based on factual determinations. And this difficulty was ultimately the reason Columbia University did not prevail in its attempt to overturn the Patent Trial and Appeal Board's judgment in an inter partes review proceeding that invalidated challenged patent claims for obviousness in Trustees of Columbia University v. Illumina, Inc.

The appeal arose from five IPRs involving U.S Patent Nos. 9,718,852; 9,719,139; 9,708,358; 9,725,480; and 9,868,985. The claims were directed to methods for "sequencing by synthesis" (SBS) (methods of nucleic acid sequencing) and recited, in separate patents, analogues of the nucleotide bases adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymidine. These derivatives were modified by having a unique detectable label conjugated to the base by a cleavable linker and further using a small, cleavable chemical moiety to block or cap the 3' hydroxyl on the deoxyribose sugar comprising the nucleotide to prevent extension of a polymerize nucleic acid chain:

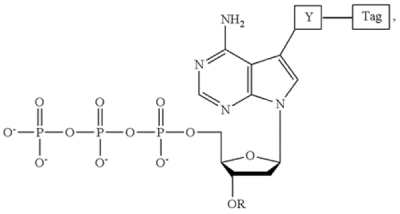

where "Y" is a cleavable linker, "Tag" is the detectable label, and "OR" is the cleavable chemical moiety in this adenine embodiment of the claimed invention; analogous embodiments for guanine, cytosine, and thymidine were provided in particular challenged patents. In the practice of the claimed methods, these species were added to a reaction mixture comprising a polymerase capable of incorporating the modified base into a growing nucleic acid strand, synthesis permitted to occur with detection of the specific detectable tags, and then cleavage of the blocking moiety and the tag with the next cycle of polymerization permitted to occur. These steps comprised a cycle of the sequencing by synthesis (SBS) reaction and could be used inter alia in automated sequencing regimes.

where "Y" is a cleavable linker, "Tag" is the detectable label, and "OR" is the cleavable chemical moiety in this adenine embodiment of the claimed invention; analogous embodiments for guanine, cytosine, and thymidine were provided in particular challenged patents. In the practice of the claimed methods, these species were added to a reaction mixture comprising a polymerase capable of incorporating the modified base into a growing nucleic acid strand, synthesis permitted to occur with detection of the specific detectable tags, and then cleavage of the blocking moiety and the tag with the next cycle of polymerization permitted to occur. These steps comprised a cycle of the sequencing by synthesis (SBS) reaction and could be used inter alia in automated sequencing regimes.

The relevant limitations of the claims involved "the use of a capping group that is 'small,' and not a 'ketone group,' 'a methoxy group, or an ester group.'" The four references used by the PTAB to hold these claims obvious included use of an allyl group which satisfies these characteristics. The references were: "(1) Tsien et al., WO 91/06678 (May 16, 1991) ("Tsien"), (2) James M. Prober et al., A System for Rapid DNA Sequencing with Fluorescent Chain-Terminating Dideoxynucleotides, 238 SCIENCE 336–41 (Oct. 16, 1987) ("Prober"), (3) Michael L. Metzker et al., Termination of DNA synthesis by novel 3′- modified-deoxy-ribonucleoside 5'-triphosphates, 22 NUCLEIC ACIDS RESEARCH 4259–67 (1994) ("Metzker"), and (4) Dower et al., U.S. Patent 5,547,839, Aug. 20, 1996 ("Dower")." The Tsien and Dower references taught SBS methods, Tsien using allyl capping groups, and the Dower patent teaching "small" capping groups, which can include allyl groups. The Metzker reference, which provided one basis for Columbia's argument that the challenged claims were not obvious, disclosed a DNA sequencing method "equivalent to SBS" but taught that allyl capping groups provided incomplete activity. The Board found that the claims to nucleotide analogues were obvious over the combination of the Tsien and Prober references or the combination of the Metzker, Prober, and Dower references (although the Federal Circuit's opinion states that the Prober reference was directed to "limitations not at issue in this appeal" and provided no further explication of that reference's relevance).

The basis for the Board's first determination of obviousness is that the Tsien reference disclosed the use of allyl capping groups in SBS methods. The Metzker reference was applied in the alternative for the same teaching, the Board disagreeing with Columbia's position that the incomplete termination teachings of Metzker taught away from Tsien's teaching that allyl capping groups could be used for SBS methods as well as concluding that "a person of ordinary skill would have understood that Metzker's experiment could be further improved by 'increasing [nucleotide] concentration or reaction time.'" The Board's conclusions were not unanimous, however, with one member of the panel dissenting on the grounds that the teachings of the Metzker reference would have "discouraged" the skilled worker from pursuing SBS methods using modified nucleotides having allyl-capped residues.

The Federal Circuit affirmed, in an opinion by Judge Lourie joined by Judges O'Malley and Reyna. The panel rejected in turn the three arguments asserted by Columbia. First, Columbia contended that the Board erred in its interpretation of the Metzker reference's teachings, and failed to recognize that those teachings would have constituted a "teaching away" by informing that skilled person that allyl capping groups were not efficient enough for successful SBS (because, according to the opinion's characterization of Columbia's argument, "SBS requires efficient incorporation of nucleotides"). The panel held that the Board's conclusions regarding the Metzker reference's teachings were supported by substantial evidence, and that teaching away must be shown by "'clear discouragement' from implementing a technical feature," citing Univ. of Md. Biotechnology Inst. v. Presens Precision Sensing GmbH, 711 F. App'x. 1007, 1011 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (quoting In re Ethicon, Inc., 844 F.3d 1344, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2017)). In the Court's view, Columbia did not meet this threshold based on three facts. First, the Tsien reference taught successful SBS methods using nucleotides having allyl capping groups. Second, the Board "carefully evaluated Metzker and found that it confirms rather than negates Tsien's teachings." With regard to whether the SBS methods were successful enough, the panel was content with the Board's determination that Metzker did not describe SBS methods using allyl-capped nucleotide analogues as failures. And third, while the art taught SBS methods using alternative capping groups the existence of "better" alternatives does not negate "inferior" alternatives in the prior art from supporting an obviousness determination.

Columbia's second argument, that the skilled worker would not have had a reasonable expectation of success in achieving SBS using analogue nucleotides comprising allyl-capped moieties, was equally unavailing. The panel's basis for rejecting this argument was that a "reasonable expectation of success" does not require "the best of all possible results." (And in a wonderful aphorism, the opinion notes that "[s]uccess may not have only one definition." Words to live by indeed.) Once again, the Court held that the Board's findings on the reasonable expectation of success issue was supported by substantial evidence. These findings include as a side note that Illumina had in a separate reexamination made the argument that the Tsien reference would not have provided a reasonable expectation of success for SBS methods, which the Board and the Court rejected because in that reexamination the priority date (which affected what was known by the person of skill in the art) was 1994 rather than, as here, October 2000. With regard to the application of the inefficient termination by allyl capping moieties in Metzker, the panel agreed with the Board that the skilled worker "would have known that 'increasing concentration [of nucleotides] or reaction time could help incorporation efficiency.'" Despite the necessarily speculative nature of that finding the Court held that the Board was entitled to rely on Illumina's expert to support it. And the panel refused the invitation it perceived Columbia was making that it "reweigh" the evidence to come to a different conclusion.

Finally, Columbia's own specification provided support for the Board's reasoning that the skilled worker would expect (reasonably) that nucleotide analogues comprising allyl capping moieties could be used in SBS methods. As has frequently been the case in adverse decisions in other contexts (see Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Sequenom, Inc., for example), disclosure intended to render claims as unlimited as possible here were used to support their invalidity. Indeed, Columbia's patent cited the Metzker reference "as evidence that allyl groups can be 'used to cap the 3′-OH group using well-established synthetic procedures'" (emphasis in opinion) as well as other positive statements about this reference. And the opinion cited PharmaStem Therapeutics, Inc. v. ViaCell, Inc., 491 F.3d 1342, 1362 (Fed. Cir. 2007), for the proposition that "[a]dmissions in the specification regarding the prior art are binding on the patentee for purposes of a later inquiry into obviousness" (itself a quote from Constant v. Advanced Micro-Devices, Inc., 848 F.2d 1560, 1570 (Fed. Cir. 1988)). The opinion asserts that "[i]n sum . . . Columbia has not pointed to any flaw in the Board's analysis." In the Court's view, the Board was given "two alternative theories" of whether (or not) the skilled artisan would have had a reasonable expectation of success in using detectably labeled nucleotide analogues comprising allyl capping groups in SBS methods and substantial evidence supported their conclusion.

As for Columbia's third argument, that the Metzker teachings (as flawed as Columbia contended they were) were limited to adenine analogues, and did not support obviousness of challenged patents relating to guanine, cytosine, or thymidine analogues, the panel summarily rejected it, stating that the Board had considered the evidence to support application of these references in its obviousness rejections for these patents as well, and substantial evidence supported the Board's conclusions.

The message is clear: a patentee (or applicant) facing the Board's invalidation (or rejection) based on obviousness will find it very difficult to overturn unless the factual basis upon which the Board rests its obviousness conclusion is not supported by substantial evidence. This reality suggests that the fight must be had before the Board, with as much contrary evidence as possible of whatever form or type supports a conclusion of non-obviousness. Because cases like this one strongly suggest that it is unlikely that there will be another opportunity to prevail before the Federal Circuit.

Trustees of Columbia University v. Illumina, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2021)

Nonprecedential disposition

Panel: Circuit Judges Lourie, O'Malley, and Reyna

Opinion by Circuit Judge Lourie